Ben Jacks

Miami University, Oxford, Ohio

jacksbm@miamioh.edu, benjackscreative@gmail.com

Summary statement

Extending a larger project focused on how numentectonic, or spiritual-architectural, photographs represent architectural atmosphere and ambience, this paper examines images reflecting human displacement through war, genocide, mass murder, and environmental disaster.

Topic

Subject photographers and projects include Karam al-Masri, on the Syrian war; Susan May Tell, A Requiem: Tribute to the Spiritual Space of Auschwitz; Juan Orrantia, Normalcy: moments of imagination and remembrance; and Sebastião Salgado, including the projects Workers (1993), Migrations (2000), and Genesis (2013).

Scope

Offering highly personal stories, each photographer’s private biography and public reflection represents a particular relationship to home and homeland: being rendered homeless; transforming, observing, and returning. Each photographer’s work in some way evokes the atmospheres of spiritual loss and authentic dwelling. This is basic research in a complex field working toward greater understanding of how photographic images frame our understanding of spiritual-architectural spaces.

Karam Al-Masri

Aleppo, Syria, AFP / Karam Al-Masri, March 2015

Karam Al-Masri was a twenty-year old, second year law student in his home city, Aleppo, Syria, in 2011 when anti-government uprising and street protests began. An entirely self-taught photographer, videographer, and journalist, encouraged by his parents to engage as a citizen, he joined the street protests. The government soon imprisoned him and tortured him for a month, including a week in isolation. Released in 2011 during an amnesty, al-Masri continued afterwards to participate in peaceful protests. Of that time he wrote, “There was no bombing. There was nothing to fear but detention and snipers in the street.”[1] In July, 2012, Aleppo was divided in two, the eastern side held by rebels and the western side by the government regime. In 2012 al-Masri became a cellphone cameraman, filming protests, uploading images online, teaching himself by looking at other professionals’ work; in 2013 he became a freelance photographer and later a videographer for L’Agence France-Presse (AFP). In November, 2013 the Islamic State group Daesh kidnapped him, holding him for 165 days. In 2014, when al-Masri was still captive, his parents were killed when the building where they lived was bombed.

The image above shows buses stood on end as a makeshift barrier to block the view and defend against government snipers. Interviewed in 2017 for the Washington Post, after he had left Syria and sought sanctuary in Paris, al-Masri remarked of this particular photograph that he looks at it again and again because, “This is in my neighborhood. This was my home.”2 For al-Masri, the trauma of losing all family, losing friends, and being rendered homeless, is never far away.

Susan May Tell

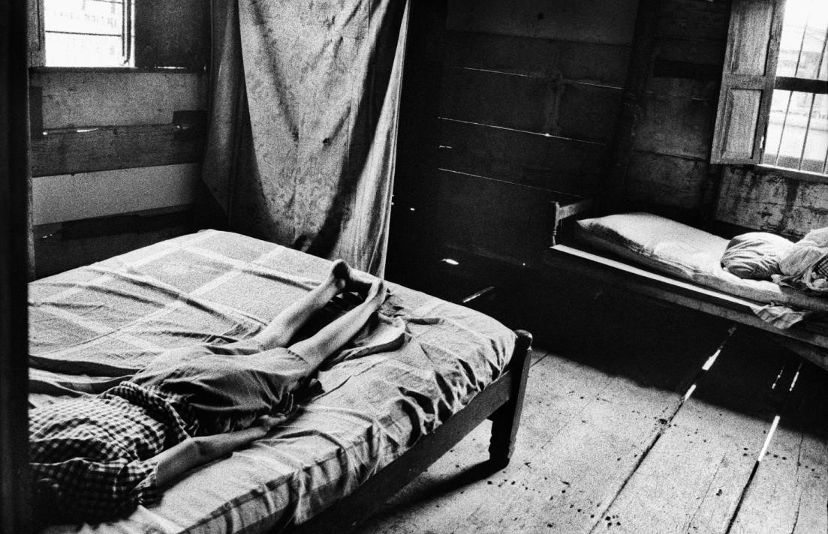

Requiem 14, 1998 © Susan May Tell, susanmaytell.com

Susan May Tell,a news/editorial photographer has had a long career with The New York Post, The New York Times, Time, LIFE, Newsweek, and other publications; she is the author of several photographic portfolios on diverse subjects. Almost by chance, and without a particular intention, Tell went to Auschwitz while traveling in Eastern Europe in 1998; she photographed some of the remains of the concentration camps in a single day, of which she writes, “I walked the grounds in silence, in meditation . . . and tried to capture the energy that lives in that space.”[2] Eschewing the museum and memorial elements, focusing on the periphery and decay, Tell raises certain questions: What is to become of the site in the future? How should it be remembered? In what particular ways has the site of such banal terror and cruelty become sacred ground? A traveling exhibition of 17 four-foot by six-foot silver-gelatin prints transforms the galleries in which it is installed into sacred space, reinforcing the theme of Auschwitz as sacred space.

Juan Orrantia

Juan Orrantia, Normalcy: moments of imagination and remembrance, explores the aftermath of a massacre of 30 men that took place in the Columbian town of Nueva Venecia on November 22, 2000. The photographs, taken in 2006-2007, are wide ranging in terms of mood and subject matter, depicting emotions from joy to boredom and “heaviness,” human interactions and activity, and the emptiness of spaces. The exhibition includes video of still images, text, and ambient sound. The all-pervasive atmosphere of the “aftermath of terror,” subsumed mostly in silence, is the main subject. The photographs show the daily and ordinary situation in which such an atmosphere lingers.

An essay, “Where the Air Feels Heavy: Boredom and the Textures of the Aftermath,” published in

Visual Anthropology Review,4explores the aftermath both concretely and evocatively. As an ethnographic project, the essay works with text and images because only together is it possible to express the sense of time, mood, and place. Citing precedents for expressive practice in ethnographic field work, Orrantia writes,

So it is to the lived experiences of dreams, of fantasies and imaginations, to empty spaces, twisted looks, twisting bodies, and histories that I turn as alternative forms of narration that register the slippages by which death and terror get imprinted in the linings of boredom. They are the little stitches that hold together the mantle over that apparent nothingness, that make the scenes that one as a stranger sees as empty, feel so heavy under the blazing sun.[3]

For Orrantia, it is only through the creative and expressive process and potential of the photograph that he can get at the atmosphere of the place and “engage the memory of the massacre.” The atmosphere of the realized photograph reaches only part way toward capturing the atmosphere of the place depicted, which is more than can be hoped for given the magnitude of its past.

Sebastião Salgado

Rwandan refugees, Benako, Tanzania, 1994, Sebastião Salgado/Amazonas Images

Sebastião Salgado was born in 1944, near Aimorés, Brazil, in the Doce River valley. As a young boy he lived on a 1,740 acre family farm surrounded by rainforest that supported a diversity of plants and animal life. He remembered this place fondly, but left to study economics at the University of São Paulo. He traveled extensively to work on development projects, which led him to photography. He abandoned economics completely for photography in 1973. He was soon working as a photojournalist and winning awards. In 1994 he established his own agency, Amazonas Images, with his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado. Salgado works on projects of his own choosing, publishing these as books, and mounting exhibitions.

In Salgado’s telling, his body of photography pivots around the late 1990s. Up until this time his work had been largely focused on human misery: starvation, war, poverty, migration, and toil. He was living much of the time in Rwanda, photographing the genocide, witnessing thousands of deaths per day. He had lost all faith in the human species, and in photography itself. He was extremely ill and consulted with a doctor in Paris who told him that he was not only ill, but dying, and that he needed to stop traveling, stop photography, stop bearing witness. At about the same time Salgado and his wife acquired the family farm in Brazil, which was overgrazed by cattle: thoroughly degraded, stripped of all vegetation, devoid of water. In Salgado’s words, “When we received this land, this land was as dead as I was.”[4]

Fazenda Bulcão, 2000 & 2013, Sebastião Salgado/Amazonas Images

Lélia and Sebastião Salgado set about transforming the farm, Fazenda Bulcão, returning it to 90% rainforest, planting 200 species of plants, and establishing an environmental education center and restoration training center, widely impacting the Doce River valley around Aimorés.

Salgado’s photography changed too, turning from human catastrophe to natural beauty and the human home. Subsequently, the exhibition Genesis (2013), which traveled to more than 15 cities, is considered the most visited photography exhibition of all time.

Conclusions

This conference presentation considers several images from four photographers, representing different genres, subjects, working methods, and personal stories—all illuminating the themes of displacement, transformation, and return. In the relatively narrow corpus of photographs focused on spiritual qualities, or atmospheres, of architecture, cityscape, and landscape, these images begin to suggest a useful taxonomy. This taxonomy includes conceptual groupings: multisensory elements; atmosphere vs. form; memory and imagination; past/present/future; sacred/profane, etc. A photograph is itself a displacement from the actual scene and setting depicted, a fact that must always be borne in mind when considering atmospheres. Moreover, the rhetoric of photographs derives from the history of the medium, the history of art, the act of framing, and the communication of character, metaphor, and allusion. The taxonomy helps suggest and develop conclusions about the relationship between numentectonic images and their actual source subjects and settings in architecture and landscape.

[1] Karam Al-Masri, Rana Moussaoui, “Covering Syria through hunger and fear,” L’Agence France Presse blog, 26 September, 2016. [https://correspondent.afp.com/covering-syria-through-hunger-and-fear] 2 Caitlin Gibson, “From behind a camera, he chronicled a war — and the destruction of his home town,” Washington Post, November 26, 2017.

[2] Susan May Tell, A Requiem: Tribute to the Spiritual Space of Auschwitz, exhibition catalog,2013. 4 Juan Orrantia, “Where the Air Feels Heavy: Boredom and the Textures of the Aftermath,” in Visual Anthropology Review, Vol. 28, Issue 1, 2012, 50–69.

[3] Ibid. 55.

[4] Sebastião Salgado, “The Silent Drama of Photography,” Ted Talk, February, 2013.

[https://www.ted.com/talks/sebastiao_salgado_the_silent_drama_of_photography#t-385560]