Sanda Iliescu

The University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA sdi5h@virginia.edu

We may live without [architecture], and worship without her, but we cannot remember without her.

John Ruskin, The Lamp of Memory, 1848

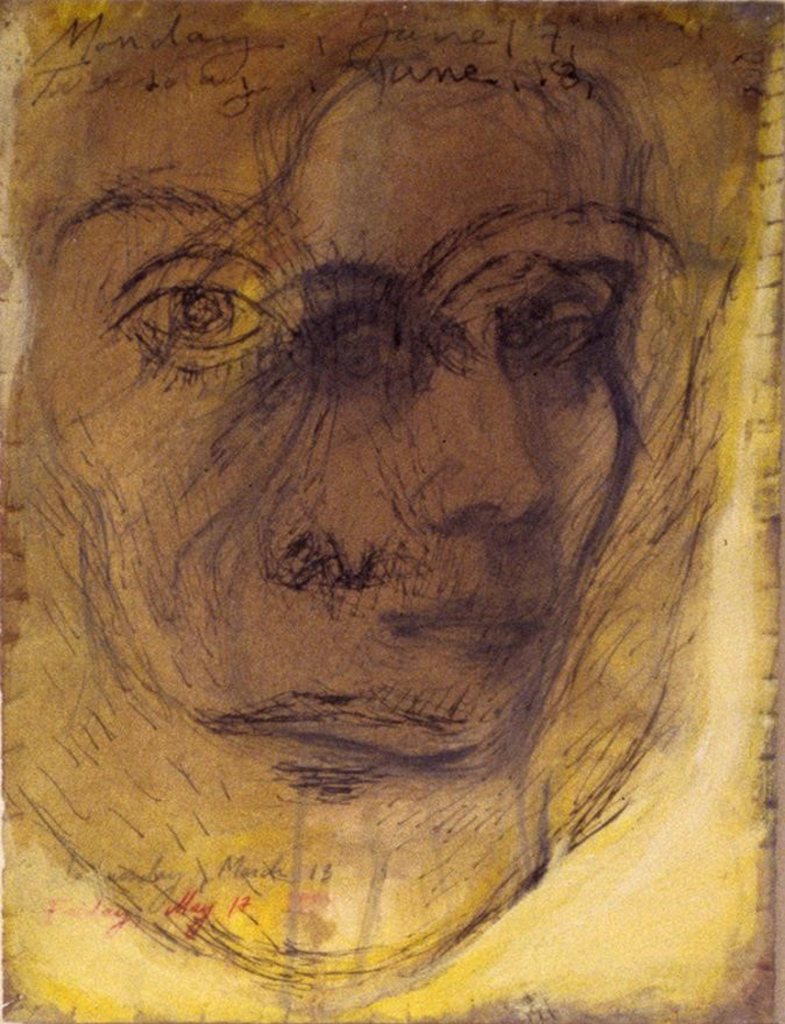

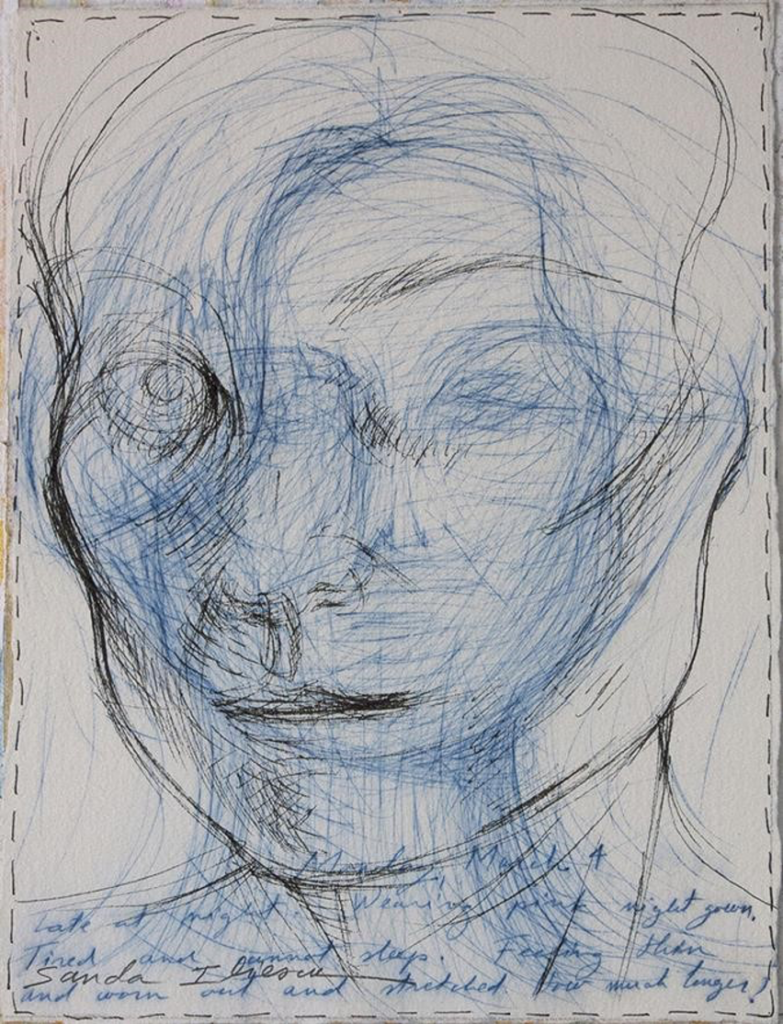

What was it like, being a refugee? Was I ever hungry? Did I sleep on the streets? Did I miss my home? These are the sorts of questions people ask me once they learn I was a refugee. When I was younger, I answered such questions with polite platitudes, saying as little as possible, and rarely trying to give thoughtful replies. I did not like looking back. It made me feel different, and I wanted to blend in; I wanted to speak English so fluently that people would not know I was born in a different country; I also dreamed of having a different sort of face: of being blonde or having blue eyes… If I wanted to become an American, I could not dwell on the past: on who I had been before I came to the US as a 17-year old; on my life in Communist Romania, from which my mother and I had fled; or my time in Germany, where we had sought asylum; or the poor neighborhood in Queens, NY, where we eventually settled. I was in an in-between place. I was no longer a Romanian, but I was not an American either. I was neither of this place, nor of the other. Sometimes I felt like a faceless person, as if a part of me had been erased. As an adult I have sometimes wondered whether I could not retrieve some of my past— that is, remember what I once consciously suppressed. Several years ago I turned to artmaking to help myself do this: for three years, I made a self-portrait every day. The close examination of my face, and the daily drawing and collage-making process became ways for me to recover my memories and feelings—those parts of myself I had lost. More recently, I have begun writing about my past. With words, I try to paint a picture of what it was like to be a refugee—both what happened to me, and the many shades of feeling— the fear, trauma, and pain—that I experienced.

If drawing my own face each day was difficult, writing about the past has been even harder. My memories feel blurred and uncertain. A lot has been lost. Yet what is still present— sometimes quite vividly—is the architecture. Not the architecture of special or famous buildings, but of ordinary places: the rooms in which my mother and I lived, the streets we walked, the kitchen and clothing store in which we worked. I am able to recall not just the geometry and proportions of those spaces, but also the ways in which my body fit within them: the way I felt as I stood, or walked, or sat, or lay down to sleep. As I imagine myself re-inhabiting those long-ago places, one feature always stands out: the materials of which they were made, substances such as concrete, wood, or stone. The physical, visceral experience of all these materials comes back to me now. I remember not only how they looked but also how they felt to the other senses: the soft feel of the grass outside my childhood apartment in Bucharest, for instance, or the dank smell of carpeting in a

basement room in Germany, or the hard asphalt streets of New York on which for the first time I met homeless people.

In the presentation I will give at the conference, I will read five brief descriptions of places, each seen through the lens of a specific architectural material. I would accompany these readings with images of my self-portraits. Below are excerpts from two of the descriptions, and reproductions of 5 self-portraits.

iron

… The women talked, and drank Turkish coffee. I played on the floor—I still remember the feel of that worn Persian rug on the wooden floor. Every once in a while, my ears perked up when I heard the phrase “cortina de fier” (the iron curtain). In my mind’s eye, I saw a huge curtain with folds resembling those of real cloth but immovable the way a sculpture of a curtain would be. It was made of iron and rose straight out of the earth. It was very tall, as tall as the tallest building I knew, which was twelve stories high. There was no way to get across this curtain made of iron. But the women sometimes discussed tales of escape, possibilities of fleeing; a clever shoemaker had done it once, they said, crossing the frozen, snow-covered Danube dressed in white…. But that iron curtain was a fearsome thing to me. All I had to do was say the word “fier” (iron), and I immediately pictured the iron curtain next to me. I was so close that I could tap it and hear the sounds it made, and I could look up and see birds flying next to the iron folds. At the base of these folds, lying on the muddy ground, I pictured rusted iron tools, crowbars, and nails. Sometimes I also saw a small figure dressed in white: that clever shoemaker who had escaped – the man who had found a crack in the curtain.

wall-to-wall carpeting

… We were underground. My mother locked the door and placed the key on a small wooden dresser drawer. The windowless room had a strong, sickening odor: a cold, humid and moldy kind of smell. We had just descended a staircase, which, like the room, had “wall-to-wall carpeting”—an expression I only learned much later. I had never seen floors covered in this way. In Romania, floors were tiled, or made of stone or wood. Why cover a floor with carpet-like material in this way? How could you sweep or clean it? Perhaps you didn’t: this strange floor was certainly stained and dirty. I remember also the walls: they showed signs of “igrasie” or moisture damage…. On our first night, I sat on the edge of a single bed. My mother sat on another, and we faced each other.

She tried to be cheerful. I too tried to put on a smile. “So we are finally here,” my mother said. “Thank goodness we can rest now; we have beds in which to sleep.”

References

Gaston Bachelard. The Poetics of Space (London: Penguin Classics, 2014)

Italo Calvino. Invisible Cities (New York: Harcourt Brace Jowanovich, 1978)

Julia Creet and Andreas Kitzmann. Memory and Migration: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Memory Studies (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011)

Donlyn Lyndon and Charles W. Moore: Chambers for a Memory Palace

(Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1994)

Mostafavi Mohsen. On Weathering: The Life of Buildings in Time (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993)

Christian Norberg Schultz. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture

(New York: Rizzoli, 1980)

Clare Rishbeth and Mark Powell. “Place Attachment and Memory: Landscapes of Belonging as Experienced

Post-Migration.” In Journal of Landscape Research, 38:2

John Ruskin. The Seven Lamps of Architecture (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1979)

Leila Scannell, R.S. Cox, S. Fletcher, and C. Heykoop.“That was the Last Time I Saw My House: The

Importance of Place Attachment among Children and Youth in Disaster Contexts.” In American Journal of Community Psychology, 58 (1-2)

Dylan Trigg. The Memory of Place: A Phenomenology of the Uncanny (Athens: Ohio University Press,2012)

Christa Wirth. “Memory and Migration: Research.” In The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014)

Peter Zumthor. Atmospheres: Architectural Environments, Surrounding Objects (Basel: Birkhouser, 2015)

Peter Zumthor. Thinking Architecture: (Basel: Birkhouser, 2015)

Sanda Iliescu

Timeline (A Self-Portrait Every Day)

Colored pencil on paper

Sanda Iliescu

Timeline (A Self-Portrait Every Day)

Watercolor and ink on paper

Sanda Iliescu

Timeline (A Self-Portrait Every Day)

Watercolor, gouache and ink on paper

Sanda Iliescu

Timeline (A Self-Portrait Every Day)

Ink on paper

Sanda Iliescu

Timeline (A Self-Portrait Every Day)

Watercolor, ink, metal staples and plastics on paper