Miriam Gusevich

The Catholic University of America

gusevicm@cua.edu

Jay Kabriel

CUA (In Memoriam)

Introduction

Public monuments tell stories, experientially and symbolically. Spatially, the monument is a focal point, an intervention that animates public space. Politically, the monument is an intervention that animates public passions.

Public monuments are in crisis worldwide. In 1937, Lewis Mumford declared the “Death of the Monument”1, yet monuments have come back to life with a vengeance: old monuments are tumbling down, new monuments to the previously marginalized are proliferating. Erica Doss, in “Memorial Mania” analyzed the urgent desire in America to claim those issues in prominent public spaces as an obsession with memory and history. 2

Maurice Halbwachs, in “Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire” (1925) advanced the concept of collective memory as a social construct, shared across an informal “cadre” of participants 3. Pierre Nora, in “Between Memory and History” (1989) observed:

“There are “lieux de memoire”, sites of memory, because there are no longer “milieux de memoire” real environments of memory.” 4

History and tradition frame our civic lives, yet they are very problematic5. Andreas Huyssen has critically examined the contemporary tribulations of history, memory, and the city6. Most recently, Timothy Snyder, the historian of totalitarian regimes, has warned us to uphold the truth of history vs. the passions of memory7.

People long for monuments to tell their story, to honor their people and their cause, by physically commanding the public’s attention in the public square. Yet these stir public passions. Public controversies around monuments focus on the politics of representation. Whose memory?

To lower the temperature, instead of WHO, let’s consider HOW. For the sake of clarity, I propose a tripartite typology of monuments.

1. The traditional, Figurative Monument.

This fulfills the conventional expectations of what Alois Riegel called the “intentional monument”8; it promises immediacy, transparency, and plenitude. These might be allegorical or historical figures. They are also the most controversial.

Religious figurative monuments offer consolation; devotional images are venerated by iconophilia and yet, these could be condemned as heretical and vulnerable to iconoclasm.

Since ancient times, secular monuments to rulers and heroes sought to bolster political legitimacy, to inspire (or intimidate) their subjects. In reaction, after regime change, these monuments have been the target of “DamnatioMemorie”and were destroyed by official decree or by revolutionary action.

2. The Avant-Garde Counter-Monument.

This rejects the traditional expectations of a figurative monument; instead of consolation or inspiration, it offers provocation.

James E. Young coined the term counter-monument to describe Holocaust Memorials by avant-garde artists in a contrite Post War, Democratic Germany.9 Instead, I situate the counter monument with the interwar Avant Garde’s Agit-Prop: Tatlin’s Tower, designed for Lenin’s Propaganda Machine and embraced by Dada. They rejected aristocratic kitsch and advocated provocation as a necessary tonic against bourgeois complacency. As Robert Musil remarked: “There is nothing in the world as invisible as monuments.”10 Is that true?

Artistic provocation is (and should be) protected as free- speech in a liberal Democracy.11 In the private space of a gallery or museum, artistic provocation can be enjoyed as a source of frisson. In a public space, open to all citizens, it can be an insult and subject to vandalism. For Kant aesthetic judgment is “disinterested” by holding in abeyance political and social judgments to protect artistic values. Artistic provocation for its own sake betrays the values of the Enlightment.

3. The site as a monument: Urban Pentimento

Instead of the traditional figurative or the counter monument, to mark and commemorate events at the actual site, is the most ancient and still most compelling monument. Masada, The Wailing Wall and Treblinka. Recent examples: Michael Arad’s Memorial to 911, Gunter Demnig’s Stumbling stones, Micha Ullman’s The Empty Library in Babelplatz, Berlin offer a lesson in humility.

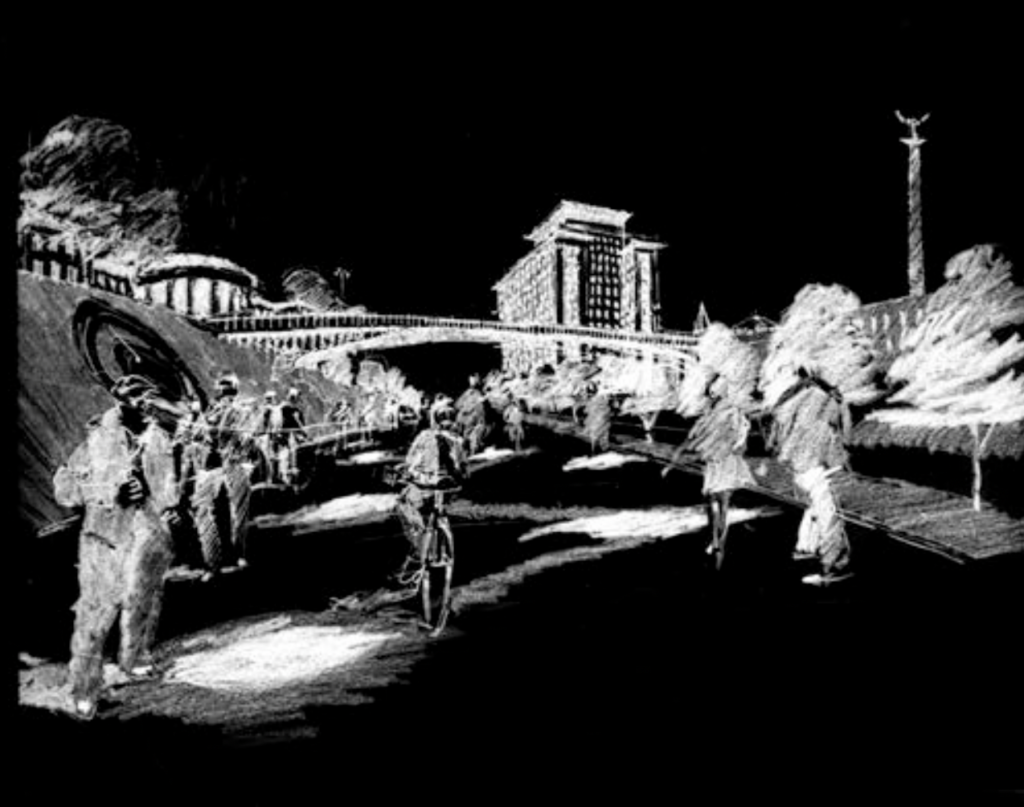

I call this Urban Pentimento. Pentimento, from Italian, pentirsi, means repentance. Like a Palimpsest, it refers to the layers of change over time; pentimento goes beyond it to acknowledge the emotional and artistic challenges of rebuilding a broken world. Like “Kintsugi” in Japanese pottery, urban pentimento tenderly gathers the broken fragments as treasures to honor the tragic past and build a more hopeful future. I will illustrate this with two of my projects in Ukraine: Constellations, for the martyrs of Euro-Maidan, and Yahrtzeit Candles, for Babyn Yar.

Conclusion.

Public monuments stir public passions; these are powerful forces. Provocation and anarchism are not emancipatory per se; they can even be anti-democratic. As we have witnessed with the recent insurrection of January 6th, stirring public passions can be dangerous, with dire consequences. Populism can be used to promote fake histories and propaganda, to celebrate misogyny and white supremacy, to silence the oppressed, to erase and to forget. The politics of grievance can be dangerous to our liberal democracy.

As James Madison wisely stated, in Federalist 49, it is in the long-term public interest to temper public passions, and to promote public tranquility as the foundation for public trust in democratic institutions12. Ancient Romans and the Founding Fathers wisely understood human nature, and cultivated tolerance to create a space for an inclusive multi-cultural and multi-religious polity.

As citizens, let’s honor history and memory, respect truth and justice. As designers, through storytelling, we can help steer public passions to build public trust. These civic actions bind people to places and affirm life and love.

1 Lewis Mumford, “The Death of the Monument,” in Circle: International Survey of Constructive Art (London: Faber and Faber, 1937), 263-270. Included in: Mumford, Lewis, 1938. The Culture of Cities, New York : Harcourt, Brace and Co., p. 433 – 439.

2 Doss, Erika. “Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America”. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2010.

3 Halbwachs, Maurice (1925). Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire (in French). Paris: Librairie Félix Alcan.1925. Halbwachs, M. (1992 [1951]) The social frameworks of memory, in On Collective Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 37–189.

4 Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: the lieux of memoire”. Representations, Vol. 26 Spring, 1989; (pp. 7-24).

5 Hobsbawm, E. and Ranger, T. (eds.) (1983) The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

6 Huyssen, Andreas. Memory things and their temporality. Memory Studies, 2016, Vol. 9(1) 107 –110.

https://doi.org/10.1177/175069801561397 . Huyssen, Andreas. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 2003. Huyssen, A. Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia. New York: Routledge.1995. Huyssen, Andreas. 1986. Afterthegreat divide: modernism, mass culture, postmodernism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

7 Snyder, Timothy, “The War on History is a War on Democracy”.The New York Times Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/29/magazine/memory-laws.html

8 Aloïs Riegl, ”The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin,” trans. Kurt W. Forster and Diane Ghirardo, in Oppositions, n. 25 (Fall 1982), 21-51. German Original. Aloïs Riegl, Moderne Denkmalkultus : sein Wesen und seine Entstehung, (Wien: K. K. Zentral-Kommission für Kunst- und Historische Denkmale : Braumüller, 1903).

9 Young, James E. “The Counter-Monument: Memory against Itself in Germany Today.” Critical Inquiry18, no. 2 (1992): 267–96. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343784.

The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 27-

48. “The Stages of Memory: Reflections on Memorial Art, Loss, and the Spaces Between”. Amherst; Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016. Accessed January 22, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1hd19w5 .

10 Musil, Robert, and Peter Wortsman. 2006. Posthumous Papers of a Living Author. Brooklyn, NY: Archipelago Books, Print.

11 See: Immanuel Kant, Critique of judgenent, trans. J. H. Bernard (New York: Hafner Press, MacMillan, 1951 ), 38. Also quoted in Peter Burger, Theory of the Avant Garrk (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 43.

12 Madison,James.”FederalistNo.49″. The Federalist Papers. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on May 7, 2009.