Trent Smith

University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah

htsmith@gmail.com

http://www.arch.utah.edu

Background

The Navajo Nation, culture, and architectural manifestation, is most often found in ruin, both figuratively and physically. Focusing on people and place, who have undergone a continuous disruptive renovation process since their first visitors arrived hundreds of years ago, this paper looks at important disruption of traditional Navajo culture, the turmoil behind it, and how efforts are being made to reintroduce ancient concepts and forms at differing scales and the benefit they bring.

Setting the Stage

[…] yet if the light goes, the Nava[j]o becomes uneasy. The night holds many terrors for him, haunted by spirits and worse, by beast men perhaps and unfriendly souls and unmentionable dangers. The Navaho make all the noises of darkness in their night dances, especially in the yeibichai. These are for the healing of individuals: the sickness of one may pull all down. There is good reason for the Navaho to feel some uneasiness, in view of the fact that he is almost the only one of the Indians of North America to live alone.

He does not gather willingly in villages like the Hopi and almost everybody else, including all those swaggerers on the plains. Instead, he occupies his own tiny hogan alone in the vast expanse with his nearest neighbor set at what one might call a family’s grazing distance away from him. Only in this way could his dry rose-and-amethyst desert be occupied–by this willingness of men to spread out across it in order to make do with the scanty water. Each hogan is thus a little haven of warmth and coolness […] being nothing less than a universe within itself[…][1]

Architecture of Earth and Sky

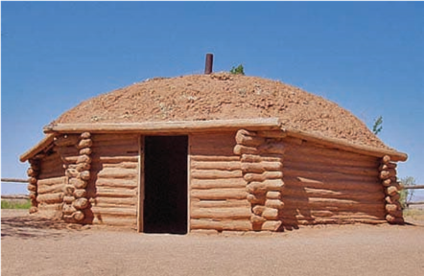

The Hogan, both the male and female versions, are based on a circular construct, similar to many Native American constructions, such as the Great Houses and Kivas of the Anasazi, referred to the Navajo as the ‘ancient ones’2. The Navajo were originally a nomadic people, and the male Hogan lends itself to that lifestyle, but when they began to become permanently established, created the female Hogan as both a ceremonial but also familial form of their homes, always with a door facing east.

The dirt floors reminded them of their connection to the Earth, while the walls represented everything on the earth, often covered in murals and paintings or tapestries representing their livelihood and relationships with animals, plants, and each other. The roof included the sky, a hole for smoke ventilation, as well as tree limbs climbing upward towards the sun.

Many of these architectural constructs directly link to concepts in their Dine’ Bahane’ creation story, such as the 4 worlds, passed through to Earth through a circular hole in the ground, the 4 sacred mountains that provide directional pulls across their nation, and their connection to the sun, earth, and sky.[2] Materials were pulled from the surrounding lands, and created an intrinsic tie to the natural.

Image 1: Traditional female Hogan with log walls Image 2: ‘Modern’ female Hogan, with stucco and mud roof, supported by a overlapping spiral over stick frame construction on a concrete pad.

log ceiling.

Something Went Wrong

Over time, the Navajo practice of borrowing culture has led to a bastardization of their traditions, most notably their iconic architectural connection to the earth. Being forced onto reservations with even fewer natural and cultural resources hasn’t helped, obviously. Many Navajo have adopted city life, and no longer live on the reservation of the southwest, even as it gets continually smaller by land greed from their host states. Those that do stay on the reservation become restless, or hopeless, and scratch out a livelihood very different than the land supports. They are torn between continuing a legacy that is barely recognized by the country they inhabit, and the societies they want to be a part of that view their ethnicity as a hindrance instead of something of value.

In visiting the Reservation, both in town and in isolated family homestead forms, I witnessed the transition that the Navajo architecture was going through first hand. I had the fortune in 2009 to stay with a Navajo friend on a trip to Kayenta, AZ, a small town of 5,000 set in the middle of the Navajo Reservation. His lodging was government issued, as is many of the homes in Kayenta. As he was full-blooded Navajo, he told me that he had a choice in housing and chose the ‘Hogan House’ to be constructed on his property.

The government interpretation of this form is an 8 sided paneled tilt-up house, each side being roughly eight feet, which isn’t an uncommon size for the form. However this Hogan was under repair, mostly with duct tape, by the owner. I walked through the Hogan along a small path in the floor, while on all sides material goods were piled high, filling the interior. My friend was living out the American Dream in his Navajo home, filling it to the brim with the goods he saw his white man counterparts accumulate, not really realizing how much they didn’t fit in his home, both figuratively and physically.

“There is a town called Kayenta in Navajo territory. In Kayenta there is a Burger King. And in that Burger King there is a museum.”[3]

This disparity continues and permeates even to the remembrance of their involvement in ‘white mans’ history. One of the more prominent Navajo businessmen in Kayenta

Image 3: Navajo Culture Center and Code Talkers Display at Burger King has created a museum in his store, a Burger King. It was the only memorial to the Navajo servicemen of WWII for many years, until a few monuments and a finally a few exhibits were hosted in more prominent cities on the reservation in the early 2000s.[4]

Fast forward to 2010 and my education with Design Build Bluff and our new client Janet Yanito, a Navajo resident in the near-reservation town of Bluff, UT, where she had created a fortress of sorts around her mobile home with tires non-working appliances and cars, with various pieces missing. We chose Janet as a candidate for our Design Build Bluff client due to her living constraints and various situations, although the plight of the American Nightmare of materialism could be found in any Navajo resident we interviewed. There was a disparity between an ancient way of life, and the modernization of this people that was heartbreaking. Traditional architecture no longer fit, literally, and was being abandoned for a larger version of what they thought would let them be accepted and achieve status.

A Return to the Earth at Differing Densities

There are a handful of design firms and programs aimed at re-connecting the Navajo people with their traditions and sensitivity to the earth. From the new library on the Dine’ College Campus[5], the new Navajo Exhibit build in-the-round at the University of Utah Natural History Museum, to a handful of community-led design workshops in many cities on the reservation, the contemporary architectural community is slowly gaining traction on the idea that the new must return to the old if it is to impact its people in a lasting way. This paper will highlight two such design efforts, Design Build Bluff and VCBO Architecture, both of which this author is involved currently.

Design Build Bluff is a nonprofit architectural education program begun at the University of Utah, School of Architecture, under Hank Luis, framed modeled after the Rural Studio in Alabama begun by Samuel ‘Sambo’ Mockbee. Luis was frustrated with the current state of architecture, and its presumed lack of compassion towards social change, and after discussions with Mockbee, was convinced that there were areas and peoples of the Western US who could benefit from the same kind of compassionate modernism.

A few premises of the program was to use mostly recycled materials, to allow students to not only design and build the architecture, but also to interview clients and become engaged in their lives in order to fully understand the architectural solutions to their everyday needs. Often these needs include a sense of pride, a place of establishment, and a new beginning to embrace culturally ancient ideals. Many times the client starts over after a home is completed, finding that their architecture has recreated a connection to the earth and a renewed sense of belonging to their Navajo Ancestry.

In having firsthand experience with this program, I have found that a quote from their website says it best, “We don’t just build homes. We build hope.”[6] The program changes the students as much if not more than the constructions change the people. A new sensitivity to materials, a caddy eye towards reuse, and a deeper understanding of how architectural solutions really can change small habits or attitudes in its inhabitants deeply impacts the pedagogy of the program’s graduates. The scale of DBB is small, focusing on 10-15 students and a single Navajo family each semester, though it plans to increase scale in the near future. 8

Image 4: Janet Yanito painting pottery in her new Image 5 :Detail of sink, Yanito Home, Design studio designed by Design Build Bluff, 2010 Build Bluff, 2010

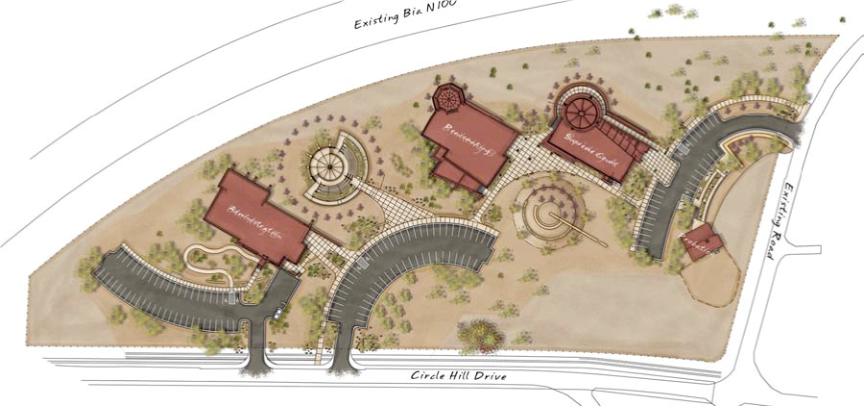

VCBO Architecture is a private design firm of about 80 members located in the heart of Salt Lake City, UT and prides itself on modern regional architecture of the surrounding area and people. They have worked with the Navajo Nation on a handful of projects, most notably the development and programming of a proposed new campus for the Navajo Supreme Court. I had the fortune to work intimately on this project, under the direction of Brent Tippets, AIA, and was able to learn firsthand from the court justices many of the traditional values that are still held in high esteem and are very symbolic. Orientation and how materials are used were pertinent concerns to the client, while we did our own research and proposed patterns and colors specific to the Navajo culture.

These sensitivities, and others, are providing a great base to have furthering discussions on how architecture can influence the livelihood of both inhabitants and visitors to the courts, and many modern architects are pushing for a sensitive bridge between the modern conveniences that the Navajo see as symbolic of progress and success, and the roots from which we believe that success must be planted.

Image 6: Site Plan for proposed Navajo Nation Supreme Court, used with permission VCBO Architecture.

References

Cook, Jeffrey: Anasazi Places: The Photographic Vision of William Current/text by Jeffrey Cook; foreword by Karen Sinsheimer. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992.

“Dinà College Library / DLR Group.”ArchDaily. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 May 2014. ONLINE

Durango Roadtripping: Having a Whopper at the Navajo Code Talkers Display & Navajo Culture Center in

Kayenta Arizona. N.p., 9 July 2011. Web. 08 May 2014. ONLINE

Gilbert, Ed. Native American Code Talker in World War II. Osprey Publishing, 2012

Luis, Hank. Design Build Bluff motto. 08 May 2014. ONLINE http://www.designbuildbluff.org

Scully, Vincent Joseph. Pueblo : Mountain, Village, Dance (Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1989) “TEDxSaltLakeCity – Hank Louis – Compassionate Sustainability – Project for Excellence in Journalism Videos. TEDxSaltLakeCity. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 May 2014.

Zolbrod, Paul G. 1984, Dine bahane` : the Navajo creation story / [translated by] Paul G. Zolbrod University of New Mexico Press Albuquerque

Image List

Image 1: Lenny. “Travel Diary.” : FAQ Hogan : Traditional Navajo House. Canyon De Chelly National Monument, 5 Dec. 2013. Web. 08 May 2014. ONLINE http://len-diary.blogspot.com/2013/12/faq-hogantraditional-navajo-house.html

Image 2: Navajo Hogan – Canyon De Chelly Arizona. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 May 2014. ONLINE

http://gocalifornia.about.com/od/toppicturegallery/l/bl_azcdc_hut

Image 3: Durango Roadtripping: Having a Whopper at the Navajo Code Talkers Display & Navajo Culture Center in Kayenta Arizona. N.p., 9 July 2011. Web. 08 May 2014. ONLINE

http://durangoworldamerica.blogspot.com/2011/07/having-whopper-at-navajo-code-talkers.html

Image 4: Janet Yanito. Used with permission. Design Build Bluff, 2010 Studio 23. May 2014. ONLINE http://designbuildbluff.org/?q=node/83

Image 5: Detail of sink. Used with permission. Design Build Bluff, 2010 Studio 23. May 2014. ONLINE http://designbuildbluff.org/?q=node/83

Image 6: Site Plan, Navajo Supreme Court. Used with permission. VCBO Architecture Archives. September 2010.

[1] Scully, Vincent Joseph. Pueblo : Mountain, Village, Dance (Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 1989) 2 Cook, Jeffrey: Anasazi Places: The Photographic Vision of William Current/text by Jeffrey Cook; foreword by Karen Sinsheimer. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992.

[2] Zolbrod, Paul G. 1984, Dine bahane` : the Navajo creation story / [translated by] Paul G.

Zolbrod University of New Mexico Press Albuquerque

[3] Durango Roadtripping: Having a Whopper at the Navajo Code Talkers Display & Navajo Culture Center in Kayenta Arizona. N.p., 9 July 2011. Web. 08 May 2014. ONLINE

[4] Gilbert, Ed. Native American Code Talker in World War II. Osprey Publishing, 2012

[5] “Diné College Library / DLR Group.”ArchDaily. N.p., n.d. Web. 8 May 2014. ONLINE

[6] Luis, Hank. Design Build Bluff motto. 08 May 2014. ONLINE http://www.designbuildbluff.org 8 “TEDxSaltLakeCity – Hank Louis – Compassionate Sustainability – Project for Excellence in Journalism Videos. TEDxSaltLakeCity. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 May 2014.