Dennis Alan Winters

Tales of the Earth : Landscape Architecture, Toronto

gardens@talesoftheearth.com

In 1939, Georgia O’Keeffe traveled to Hawai’i at the invitation of the Hawaiian Pineapple Company, the ‘pre’ of Dole Foods. She agreed to paint pineapples for their national pineapple promotion campaign with the provision she’d otherwise have time to paint what she wished. The Great Pineapple Escape of 1939. During her three weeks on the island of Maui, she painted a series of four waterfalls in the enchanting, volcanic canyon of ‘Īao Valley. These paintings served as vehicles to engage with this landscape through its three shades, or layers of meaning. This paper focuses on a third shade of engagement with landscape as platform for artistic and spiritual integrity.

Inadequately engaged with the passions of the ‘Īao Valley landscape, Georgia O’Keeffe’s aesthetic exploration investigated, assimilated and became intimately entwined with landscape, as articulated in Indigenous Hawaiian expressions of kaona, or ‘layers of meaning’.[1] Painting the waterfall sequence gradually dissolved distinctions between whom she was and where she was.

Kaona, like Tibetan Buddhist compendia and spiritual guides to sacred landscape,[2][3] regards phenomena with three shades of engagement: 1) the physical landscape of lands, waters and skies obvious and evident to the senses; 2) qualities revealed through stories or understood through analysis and; 3) an extremely hidden landscape, neither obviously evident nor logically understood. This third shade is unique to each culture: Kaona speaks of the sexually erotic play of landscape meshed with all aspects of life.3 Buddhism speaks to subtle tantric practices.[4] The entirety of the three shades, elsewhere, beautifully expressed: –

“What,” it will be Question’d, “When the Sun rises, (1stshade)

do you not see a round disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?” (2ndshade)

O no, no, I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying,

“Holy, Holy, Holy is the Lord God Almighty.” (3rdshade)– William Blake. A Vision of the Last Judgment [5]

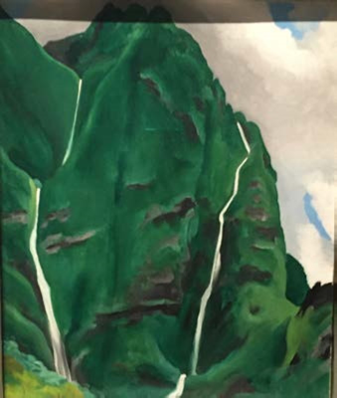

The First Shade of Engagement: Georgia O’Keeffe’s ‘Īao Waterfall 1 and End of Road served as vehicles for her first shade of engagement with landscape. The physical body of the visible landscape presented as a descriptive assemblage and geometry of topography, geology, hydrology, soils, flora and fauna. It regards the relationship between earth and sky; form and space: shape of valley, tributary gorges, magma outcrops, rock talus, crevasse and waterfall with clouds, wind and rain – nature’s arising, abiding and dissolving. Considered most ‘realistic’, to Georgia O’Keeffe’, the first shade is the least real, the least ‘Georgia O’Keeffe’.

‘Īao Waterfall 1

End of Road

The Second Shade of Engagement: ‘Īao Waterfall 2 is used to explore audible stories, tales of genealogy and history, and myths and metaphor accorded to the landscape of ‘Īao Valley. The speech of landscape, stories are bedded with the rock, immediately familiar and apparent to those who know them. More real than the first shade, Georgia O’Keeffe cultivates a deeper intimacy with landscape and its operations of nature. Subtleties of spirit, space, wind and movement abide within each stroke of paint.

‘Īao Waterfall 2

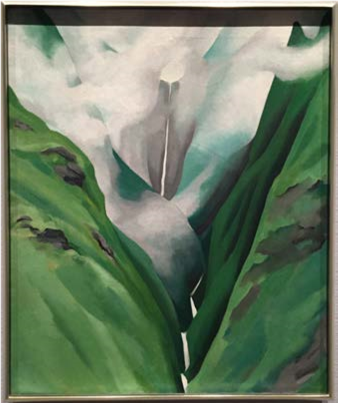

The Third Shade of Engagement: Waterfall No. III – ‘Īao Valley penetrates the most subtle relationship with landscape, stroking questions about the nature of intimacy with landscape, about the relation between self and what’s seemingly outside, the relationship between ‘who we are’ and ‘where we are’. It asks: – Is there a boundary between psyche of Georgia O’Keeffe and psyche of landscape;[6] between body parts on one side of her skin and those seemingly on the other side?

In this subtle exploration, she’s not passed into transcendence, the idea an incision into the soul of the relationship with landscape that animates and energizes her. Rather, she harnesses the all-embracing consciousness of life, so that this landscape is her ‘heaven on earth, her ‘pure land’, her Psalm 84. Exploring her immediate intimacy with the Canyon, Georgia O’Keeffe paints as Carl Jung’s: –

Psyche in accord with the structure of the universe, and what happens in the macrocosm happens in the infinitesimal and most subjective reaches of her psyche.[7]

She paints as Nagarjuna’s Prajna-paramita: the Reality of Nature, the totality of relative truth, her paint in dependence upon causes and conditions; interdependent phenomena arising, abiding and abating within as without; the symphonic rhyme of cause and effect.[8] In doing so, she paints as landscape might paint Georgia O’Keeffe. She paints the GEOPOMORPHIZING of Georgia O’Keeffe – geologic form and space ascribed to human form and space.9 Muse to landscape, she paints Neruda’s: –

I want

to do with you what spring does with the cherry trees.10

Contradicting generally held assumptions, geopomorphized, Georgia O’Keeffe doesn’t paint body parts. She paints the natural erotic engagement of complementary pairs: repose with movement, rise with fall, push with pull, flex with contract, inside with outside, concave with convex, inhale with exhale, sound with silence.

She paints the primal ecological pastime, the natural erotic engagement of complementary pairs: sky with earth; form with space; projecting landscape with embracing landscape; landscape that supplies with landscape that receives; landscape that invites with landscape that repels; winds whisking water, rainbows caressing rock, spires thrusting into sky, and clouds sliding over ridges and gliding into canyons.

Disciple of space rather than form, cloud rather than cliff; mist rather than outcrop; where otherwise she’d think they were just plainly getting in the way. She paints clouds riding wind, creeping over ridges, sliding into folds, penetrating crevasse, the magnetic vibration of Cloud and Canyon, a millimetre of electric breath between.

As an artist in search of truth, Georgia O’Keeffe’s Waterfall No. III – ‘Īao Valley is most real to her, the most embracing, the most reflective, the most definite form for intangible things in herself that she can clarify only in paint.[9] Thoughts and events of her life are indistinguishable from the entirety of nature, her symmetry with rhythms of landscape – arising, abiding and abating, exhaling and inhaling as one.

She paints Rilke’s: –

Earth, this is what you want. To arise in us, invisible.

Your dream, to enter us wholly

nothing left outside to see.[10]

‘Īao Waterfall III

References

Tanya Barson, editor. Georgia O’Keeffe (London: Tate Publishing, 2016)

Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library – Yale University Library. Letters from O’Keeffe to Stieglitz. From Alfred Stieglitz / Georgia O’Keeffe Archive Call Number: YCAL MSS 85.

Bram Dijkstra. Georgia O’Keeffe and the Eros of Place. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998)

Sarah Greenough, editor. My Faraway One: Selected Letters of Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz: Vol I, 1915-1933 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011)

Joanna Groarke and Theresa Papanikolas. Georgia O’Keeffe: Visions of Hawai’i (New York: New York Botanical Garden, 2018)

Patricia Jennings and Maria Ausherman. Georgia O’Keeffe’s Hawai’i (Kihei: Koa Books, 2011)

Barbara Buhler Lynes. Georgia O’Keeffe: Catalogue Raisonné (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999) Brandy Nālani McDougall. Finding Meaning: Kaona and Contemporary Hawaiian Literature (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016)

Georgia O’Keeffe. Georgia O’Keeffe (New York: Viking Press, 1976)

Jennifer Saville, ed. “Off in the Far Away: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Letters Home from Hawai’i” in The Hawaiian Journal of History, Vol. 46 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2012)

Calvin Tompkins. “Georgia O’Keeffe’s Vision” in The New Yorker, March 4, 1974

Dennis Alan Winters. Searching for the Heart of Sacred Space (Toronto: The Sumeru Press, 2014)

[1] See Brandy Nālani McDougall. Finding Meaning: Kaona and Contemporary Hawaiian Literature (Tucson:

University of Arizona Press, 2016)

[2] See Dennis Alan Winters. Searching for the Heart of Sacred Space (Toronto: The Sumeru Press, 2014) 3 See Amy Marsh. “Joy of the People of Old Hawai’i” in Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, Vol. 14, Feb.

[3] , 2011

[4] See Tenzin Gyatso, the XIVth Dalai Lama. Healing Anger (Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 1997): 13-15

[5] William Blake. “A Vision of the Last Judgment,” 92-95 in Geoffrey Keynes, ed. Blake Complete Writings (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979): 617

[6] See James Hillman. “A Psyche the Size of the Earth” in Theodore Roszak, Gomes & Kanner. Ecopsychology. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1995): xvii-xix

[7] See Carl Jung. Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Vintage Books, 1989): 335-336

[8] See The Large Sutra on Perfect Wisdom. Edward Conze, trans. (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1979) 9 Also see Ernest Fenollosa, proposing language based on the operations of nature, reflecting the temporal order in causation in Ernest Fenollosa. Ezra Pound, ed. The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1936). Also Mark Vernon.“The Say of the Land. Words emerge from soul of cosmos in https://aeon.co/essays/words-have-soul-on-the-romantic-theory-of-language-origin 10 Pablo Neruda. Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair. W. S. Merwin, trans. (San Francisco: Chronicle Books. 1969): XIV – “Every Day You Play”

[9] See Georgia O’Keeffe. Georgia O’Keeffe (New York: Viking Press, 1976): n.p.

[10] See Rainer Maria Rilke. “Earth, Isn’t This What You Want?” in A Year With Rilke, Joanna Macy and Anita Barrows, trans and ed. (New York: HarperOne, 2009): 162. Author has transformed Rilke’s interrogative into a declarative sentence.