James F. Williamson

University of Memphis

jfwllmsn@memphis.edu

You present a quality, architectural, no purpose. Just a recognition of something which you can’t define, but must be built… But that’s a definite architectural quality. It has the same quality as all religious places…It’s the beginning of architecture. It isn’t made out of a handbook. It doesn’t start from practical issues. It starts from a kind of feeling that there must be a world within a world. -Louis Kahn[1]

Introduction

As a teacher, I bring to my work the belief that the goal of higher education should be the development of students as fully dimensional human beings. The truly educated individual has not only acquired knowledge, but is also committed to a search for personal meaning and attuned to the spiritual aspects of existence. Because architecture has the power to inspire an experience of the transcendent, places of spiritual reflection should be provided on the campuses of our colleges and universities. A recent project assigned to my third year undergraduate architectural students explored the making of such a place on the campus of the University of Memphis.

Assignment

This assignment entailed the design of an interfaith chapel, a non-denominational place for individual and group prayer, meditation, and contemplation, as well as small worship services, weddings, funerals, etc. It was to be welcoming and inspiring to visitors of all faith traditions, as well as to the non-believer. The interior was to consist of a single room, large enough to accommodate approximately 100-150 seats. An important objective was that the chapel possess the quality Kahn referred to as “a world within a world.”

Design Issues

To inform the design process, the students were challenged in group discussions and individual critiques to reflect on the following questions:

- On a large, urban, public campus with a highly diverse population, how can a chapel which will be visited by people of many different religious and cultural backgrounds, as well as those with no particular religious faith, inspire a search for the sacred in a way that will be meaningful to all?

- What is the difference between a space and a place?

- In its making, how can a room encourage or discourage a variety of spiritual experiences, such as silent meditation, group interaction, or focus on a speaker?

- What is the relationship between structure, natural light, and an experience of divine presence?

Research

Prior to beginning design, a research phase was carried out by the students including precedent studies, site selection, and site documentation. Several contemporary chapel projects of comparable scope were investigated, including:

- Chapel of St. Ignatius by Steven Holl, Seattle University

- Class of 1959 Chapel by Moshe Safdie, Harvard Business School

- Thorncrown Chapel by Fay Jones, Eureka Springs, Arkansas

- Woodland Chapel by Gunnar Asplund, Stockholm, Sweden

The students then investigated alternative sites before making their selection, a large, open field adjacent to the University library.

As the students began their design studies, a variety of different approaches emerged, including several of striking originality. The following projects were selected for their design merit and their successful exploration of the power of architecture to inspire a search for the transcendent.

Project 1

This chapel is described by the student as a physical manifestation of concepts of the seen and the unseen as expressed by William Blake and the Apostle Paul. Blake believed that “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.” Similarly, Paul declared, “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.” Entry into a monumental, openair cylinder of heavily rusticated concrete (Fig, 1) is by way of a stepped terrace leading downward to a reflecting pool symbolizing cleansing, inner reflection, and an escape from ordinary experience. Inside, the presence of the outer world is subtly suggested by reflected light cast against the cylinder’s dimly lit inner walls, recalling Plato’s cave (Fig. 2). A conical ceiling appears to float overhead, an aperture in the center flooding the podium below with a vortex of natural light symbolically connecting the visitor with eternity.2

Design by Dustin Collins

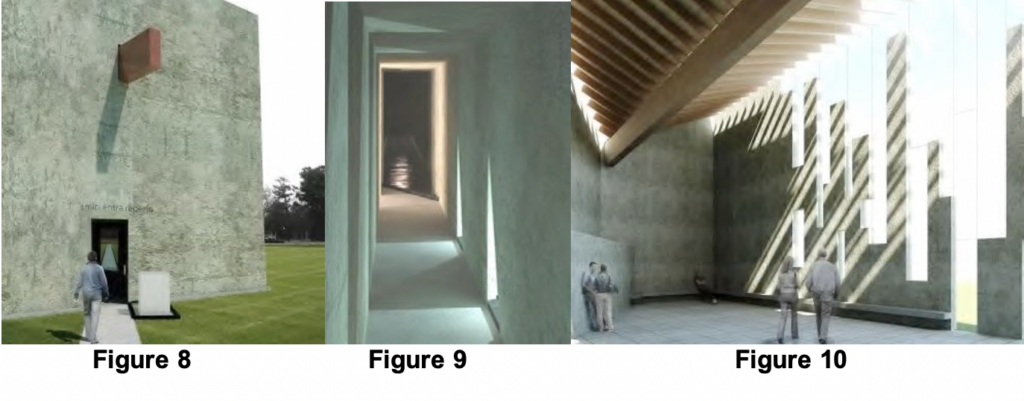

Project 2

A very different approach is taken in the next chapel. Here a series of structural vaults shape the room and celebrate the play of natural light. After moving through a small entrance vestibule, one feels that he has indeed entered “a world within a world” where filtered light from unseen sources symbolizes the four ancient natural elements, earth, wind, light, and water (Figs. 3- 4). The arched concrete baffles diffuse and add subtle color to this light, creating a sense of serenity conducive to spirituality. Beyond, the chapel opens onto a walled garden containing a reflecting pool and a louvered screen wall to admit light and a cooling breeze, again recalling the four natural elements.[2]

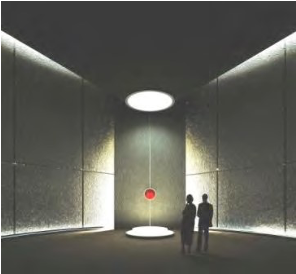

Project 3

In this project the student conceived of the chapel as a balance of opposites, two cubes of identical size, a “solid” and a “void” (Fig. 5). Entry is through the “void,” a transparent steel and glass box, and across a bridge over a pond (Fig. 6). The adjoining “solid” counterpart, a tilt-up concrete cube, contains a single room (Fig. 7). The floor is surrounded by a shallow pool, creating a central island of the same dimensions as the pond in the entry cube. The concrete walls seem to float above the water, cantilevered from four large columns at the corner, while a strip of glass at their base reflects tempered daylight into the chapel.[3]

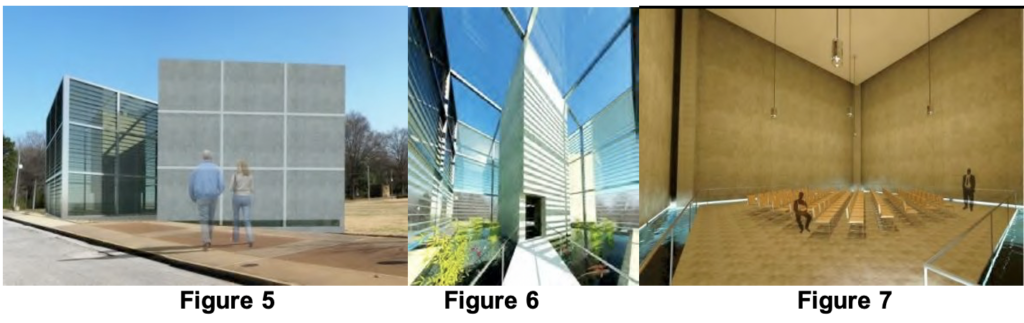

Project 4

In this chapel, contrasting elements are employed to create a sense of spiritual relief and release from the pressures of everyday existence. Approaching the ambiguous exterior (Fig. 8), one is confronted by a small door leading into a mysterious concrete corridor (Fig. 9). The corridor leads deeper into the building, growing ever darker, until the visitor abruptly turns and discovers the dramatic inner room, unexpectedly flooded with natural light (Fig. 10). Overhead, a large beam running the length of the high space supports the wood roof and provides welcome warmth and relief from the bare concrete of the floor and walls. Through contrasts of scale, texture, and light, the chapel is designed to free the mind in its search for spiritual enlightenment.[4]

Conclusions

Although these four projects are quite different, several common themes emerge. In keeping with the interfaith mission of the chapel, all avoid symbolism that could be identified with any single faith tradition. In all four a carefully considered circulation pattern symbolizes a spiritual journey from the outer world to a place of solitude and quiet reflection. All emphasize a strong sense of enclosure, focusing inward rather than on the surrounding campus. In each case the shaping of the chapel and the use of moveable chairs allow for a variety of seating configurations to accommodate the various programmed activities. And in each, the controlled use of natural light is important in the creation of an atmosphere conducive to peaceful contemplation. The main goal of the assignment was to foster among the students a greater awareness of the power of architecture to inspire an experience of the transcendent. In these projects, we see very different approaches to the making of a small interfaith chapel, a single room that as Kahn suggested, grows out of a desire to create a world within a world. It is in the making of such a room that we can hope to sense the beginning of architecture and perhaps make contact with a divine presence, the ineffable within us.

[1] From Silence and Light, first delivered at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, December 3, 1968.

[2] Design by Darius Bounds

[3] Design by Huan Tran

[4] Design by Roy Beauchamp