Mark Baechler

Laurentian University School of Architecture, Sudbury, Ontario mwbaechler@laurentian.ca

Introduction

The ‘Children of Abraham’ summon up, then, the image of a family, of siblings of the same father. The portrait is both appropriate and accurate: the communities of Jews, Christians and Muslims all claim to be in some sense the offspring of the Hebrew patriarch with whom God made his Covenant in the early days of the world. – F.E. Peters[1]

The Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity and Islam—are bound by their belief in one God. The religions share a collective history that extends to the patriarch Abraham. Despite their common origins, the faiths increasingly appear disconnected. Animosity among factions of the religions often overshadows opportunities to reflect on the traditions shared by the Children of Abraham. Many of the issues stimulating their religious divide are beyond the conventional scope of architects; the purpose of this work is to explore a potential architectural contribution toward Abrahamic understanding and forgiveness.

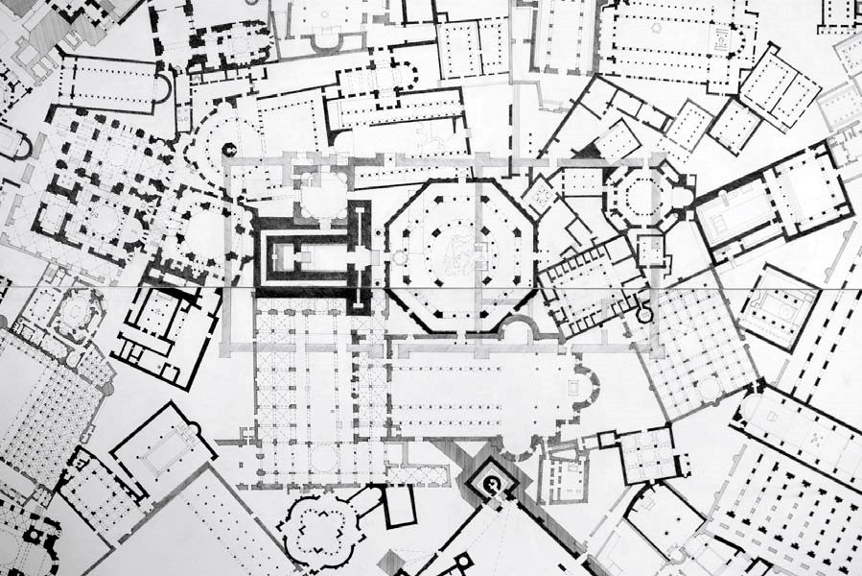

This paper discusses an architectural drawing entitled Abrahamic Architecture (Baechler, 2014).The drawing is informed by number of buildings co-authored among Jewish, Christian and Islamic architects that I term ‘Abrahamic.’ The drawing explores and presents ‘Abrahamic’ buildings as thresholds among the three religious traditions that are frequently obscured by isolated studies of Jewish, Christian and Islamic architecture. I argue that ‘Abrahamic’ buildings reveal interconnections among the Children of Abraham and an architectural dialogue of reconciliation.

Abrahamic Texts

In his seminal work Judaism, Christianity and Islam: The Classical Texts and Their Interpretation,

F.E. Peters juxtaposes a selection of passages from the religions Scriptures (Tanakh, Christian Bible, and Qur’an) and other ‘Classical Texts’ for the purposes of comparison. Providing analysis and interpretation between the numerous excerpts, he reveals latent associations among the religions and reinforces the notion of a collective Abrahamic tradition. In short, Peters’ binds Jewish, Christian and Islamic writings in one massive book and through his commentary provides the reader with a guided tour of this complex landscape.

Abrahamic Architecture

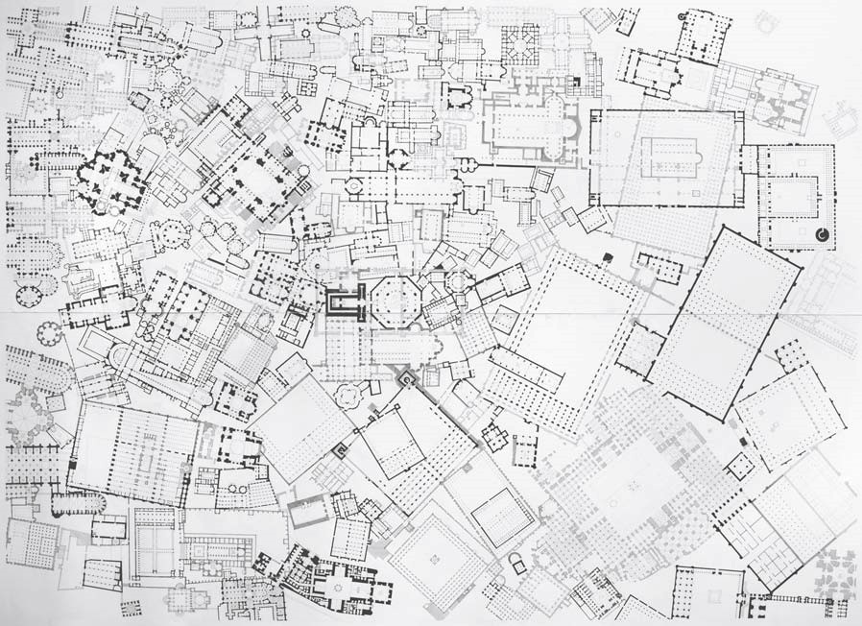

Borrowing from Peters’ method, I have employed the media of drawing to juxtapose and connect synagogues, churches and mosques in order to explore the architectural interconnections among the Abrahamic religions (Fig.1).

Figure 1. Abrahamic Architecture (Baechler, 2014) 11’-3”x 8’-4” graphite on paper.

Abrahamic Architecture displays a collection of over 180 Jewish, Christian and Islamic buildings constructed between 970 B.C.E.-1679 C.E. The scale and orientation of the individual structures are portrayed accurately. Among the many buildings depicted, seventeen are considered to be works of ‘Abrahamic’ architecture2 (Fig.2). I apply this term to synagogues, churches and mosques converted for use by another Abrahamic religion. The altered buildings are the collective work of multiple Abrahamic authors; they are not representative of a single religion. Rather, ‘Abrahamic’ buildings are thresholds among Jewish, Christian and Islamic architectural traditions. The resulting drawing emphasises the religions shared constructions by portray their collective building traditions as an expansive work of ‘Abrahamic’ architecture.

2 Jerusalem: The Temple Mount. Mecca: Kabba, Istanbul: Hagia Sophia Church-Mosque, Eski Imaret

Church-Mosque, Fenari Isa Church-Mosque, Fethiye Church-Mosque, Gul Church-Mosque, St. Saviour in

Chora Church-Kariye Mosque, Kalenderhane Church-Mosque, Manastir Church-Mosque, Sancaktar

Hayreddin Church-Mosque, Toklu Ibrahim Dede Church-Mosque. Spain: Ibn Shushan Synagogue – Santa Maria la Blanca Church , Transito Synagogue-Church, El Cristo de la Luz Mosque-Church, The MosqueCathedral of Córdoba. Damascus: Church of St. John the Baptist-Great Mosque of Damascus.

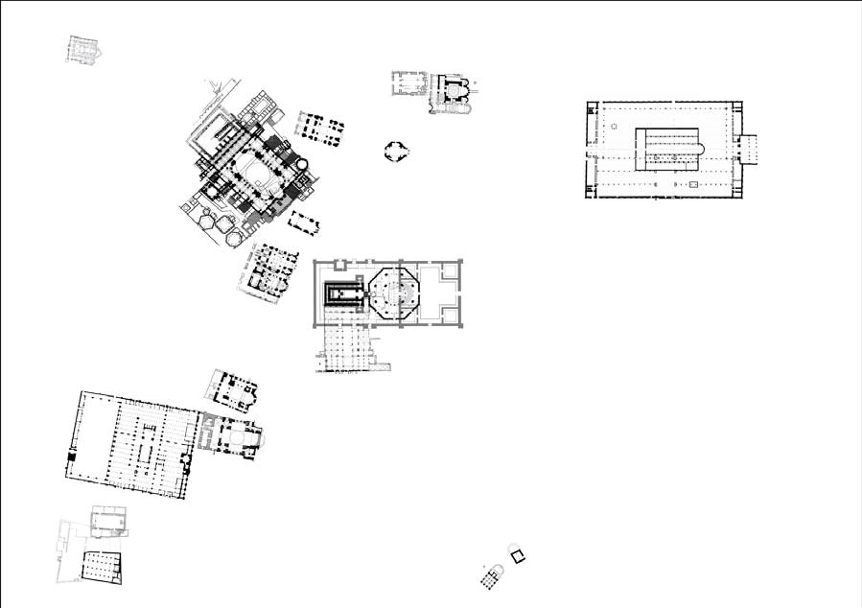

Figure 2. Within the drawing Abrahamic Architecture seventeen examples of ‘Abrahamic’ buildings serve as thresholds, interconnecting Jewish, Christian and Islamic building traditions.

Within the period of study cities residing in transitioning territories surrounding the Mediterranean Sea offer two distinctive social circumstances that foster ‘Abrahamic’ architecture; peaceful collaboration and violent conflict.[2] The Iberian Peninsula prior to the Christian seizure of the region ending in 1492 C.E. is an example of the former scenario. During this time the region was culturally diverse, housing Diaspora Jews, Christians and Muslims. Archaeological evidence suggests that several architectural collaborations among the Abrahamic religions occurred. The later scenario is exemplified in the period that followed the Christian conquest. As a result, many synagogues and mosques were appropriated by Christians. Similarly, when Constantinople was captured by the Turks in 1453 C.E. several Christian churches were converted to mosques. Despite the social conditions, peaceful or violent, the co-authored buildings provide valuable historical examples of an architectural dialogue unfolding among the faiths.

A survey of contested geography surrounding the Mediterranean Sea reveals numerous ‘Abrahamic’ buildings; the following section examines two examples.

Ibn Shushan Synagogue – Santa Maria la Blanca Church

The walled city of Toledo, Spain contains several works of ‘Abrahamic’ architecture.[3] Located in

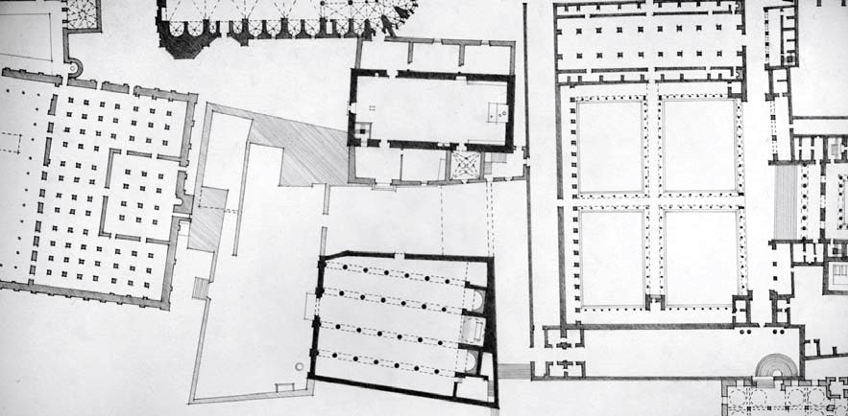

the Jewish quarter of the city is the Santa Maria la Blanca (Saint Mary of the Snows)[4] Synagogue-Church. Constructed in 1203 C.E., it was originally named the Ibn Shushan Synagogue and it held Jewish worship for two centuries until it was converted to a Christian church and renamed Santa Maria la Blanca.[5] The synagogue was built for a Jewish congregation by Moorish (Muslim) craftsmen who combined the Jewish and Islamic architectural traditions in the design of the prayer hall.

The building conforms to a slightly skewed rectangular site which is filled with five bays of varying heights aligning with Jerusalem. The bays are defined by a grid of octagonal columns crowned with ornately carved capitals. Horseshoe arches adorned with numerous variations of Islamic patterns span the columns. The grid of columns revealed in the buildings floor plan is unique among synagogues; the origins of this type have been the subject of study.[6] If the synagogue is observed in the context of the greater Abrahamic building tradition as drawn in Abrahamic Architecture, Moorish mosque typologies become convincing precedents for the gridded design (Fig.3). Following the synagogues conversion to a Christian church the interior was painted white and three apses were added to the east wall. The original Islamic patterns and symbolic Hebrew sculptures of sea shells and the Star of David throughout the building remained unmodified.

Figure 3.The Santa Maria la Blanca Synagogue – Church floor plan consists of black walls indicating the original Moorish construction, the grey hatch denotes Christian addition Church of St. Saviour in Chora – Kariye Mosque

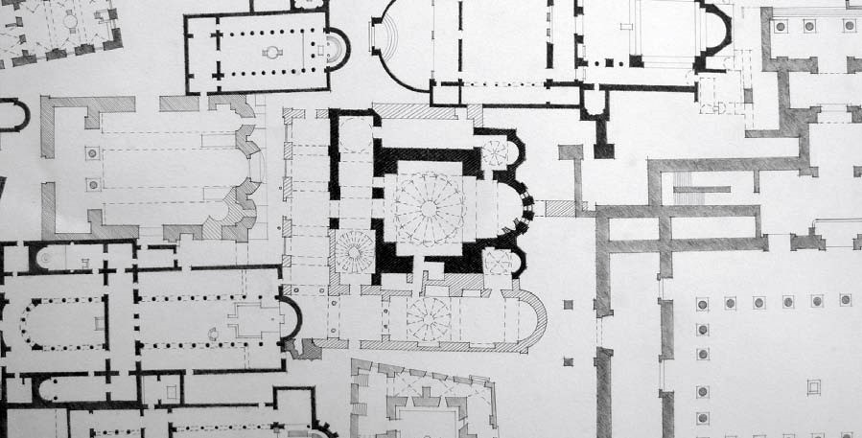

The Church of St. Saviour in Chora – Kariye Mosque in Istanbul was originally constructed for Christian worship, following the Turkish conquest of Constantinople it was transformed into a mosque. The initial phase of construction is thought to have been completed in 1081 C.E.[7] The buildings square plan and central dome is typical of Byzantine churches in Constantinople. An apse residing on the east wall surrounds the altar and provides a counterpoint to a modest narthex on the west which also serves as the building’s entrance. The church was expanded in

c.1321 C.E.,[8] when an additional narthex was added to the west and a parecclesion south of the nave. Renovations to the church were minimal when it was converted to a mosque in c.1511 C.E. Christian mosaics and frescoes adorning the interior surfaces of the church were whitewashed or covered with movable wood panels.[9] A minaret was constructed on the south west corner and a marble mihrab was sculpted in the existing apse oriented toward Mecca (Fig.4).

Figure 4.The Church of St. Saviour in Chora – Kariye Mosque floor plan consists of black and light grey hatched walls indicating the two phases of Christian construction. Turkish additions to the building are denoted with a dark grey hatch.

Abrahamic Reconciliation

Our discussion of buildings that result from contested geography is not to unearth historical differences rather to highlight the religions affinities. Following conflicts existing religious buildings were occasionally razed and the foundations were used for new edifices,[10] but often the buildings were saved and adapted for reuse. The appropriated buildings point to an Abrahamic practice of alterations and additions, not erasure.

To revise and add to an existing structure an architect is required to have a thorough understanding of the building and its cultural significance in order to enter into an architectural conversation with it. ‘Abrahamic’ buildings document an interfaith architectural dialogue that spans centuries and continents. Specific revisions made to a synagogue when it is converted to a church highlight the similarities and distinctions of Judaism and Christianity as exemplified in the Ibn Shushan Synagogue – Santa Maria la Blanca Church. Likewise, when a church is transformed into a mosque, what remains untouched illustrates the shared identity of Christianity and Islam as seen in the Church of St. Saviour in Chora – Kariye Mosque. ‘Abrahamic’ buildings display in wood and stone the religions’ mutual characteristics and serve as thresholds linking the three architectural traditions.

Figure 5. Abrahamic Architecture portrays Jewish, Christian and Islamic architecture as a unified edifice consisting of numerous alterations and additions.

Abrahamic Architecture is an investigation in architectural representation that speculates on a possible resolution of the divided house of Abraham. This paper defines the collaborative constructions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam as ‘Abrahamic’ architecture and argues these monuments illustrate the religions’ shared identity. The Abrahamic common ground that F.E Peters’ revealed in his study of Jewish, Christian and Islamic sacred texts also exists in the religions’ architecture. These shared ‘Abrahamic’ spaces encourage dialogue and forgiveness as they are, by definition, places of reconciliation.

References

Alvarez, Ana Maria Lopez and Santiago Palomero Plaza (eds.). Museo Sefardi: The Synagogue of El Transito. (Toledo: Museo Sefardi,1997).

Dursun, Haluk and Halil Arca (eds.). Chora Museum. (Istanbul: Bilkent Kultur Girisimi Publications, 2011).

Kirimtayif, Suleyman. Converted Byzantine Churches in Istanbul. (Istanbul: Ege Yayinlari, 2001).

Krinsky, Carol Herselle. Synagogues of Europe. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1885).

Larriba, Miguel (ed). Entre el Califato y la Taifa: Mil Anos del Cristo de la Luz. Actas del Congreso Internacional, 1999 (Toledo: Asociacion de Amigos del Toledo Islamico, 1999).

Pelaez del Rosal, Jesus. The Synagogue. (Cordoba: Ediciones el Almendro, 2003).

Peters, F.E. The Children of Abraham. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004).

Peters, F.E. Judaism, Christianity and Islam: The Classical Texts and Their Interpretation. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990).

Peters, F.E. The Monotheists: Volume II. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003).

The Holy Bible (NIV). (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Bible Publishers, 2002).

The Holy Qur’an. (Istanbul: Acar Matbaacilik Yayincilik Hizmetleri, 2002).

The Tanakh. (Philidelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society, 1999).

[1] Peters, F.E. The Monotheists: Volume II. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.) p.379.

[2] Egypt, Israel – Palestine, Turkey , Spain (Iberia Peninsula ) and Syria are among the numerous countries that display a checkered history of Jewish, Christian and Islamic peaceful co-inhabitation and conflict.

[3] El Cristo de la Luz Mosque-Church, Ibn Shushan Synagogue – Santa Maria la Blanca Church, Transito (or Prince’s) Synagogue-Church,

[4] Krinsky, Carol Herselle. Synagogues of Europe. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1885) p.334.

[5] Jesus Pelaez del Rosal. The Synagogue. (Cordoba: Ediciones el Almendro, 2003) p. 119.

[6] Krinsky discusses unsuccessful scholastic attempts to uncover an early synagogue type that corresponds with the gridded floor plan in Synagogues of Europe. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1885) p.333. Jesus Pelaez del Rosal suggests the plan derives from the basílica in The Synagogue. (Cordoba: Ediciones el Almendro, 2003) p. 120.

[7] Kirimtayif, Suleyman. Converted Byzantine Churches in Istanbul. (Istanbul: Ege Yayinlari, 2001) p.74.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Dursun, Haluk and Halil Arca (eds.). Chora Museum. (Istanbul: Bilkent Kultur Girisimi Publications, 2011) p.11.

[10] The Santiago del Arrabal and The Primate Cathedral of Saint Mary of Toledo serve as examples where churches were build upon the foundations of destroyed mosques following a conquest.