Tammy Gaber, PhD

Laurentian University, Ontario, Canada tgaber@laurentian.ca

Safira Lakhani, M.Arch (candidate)

University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada safira.lakhani@gmail.com

Jessica Lam, B.A.S. (candidate)

Laurentian University, Ontario, Canada jlam1@laurentian.ca

I did not want this mosque to be a big ‘shack,’ I promised the city officials this. The community was involved from the beginning and some thought that we should build a big cheap building to get the most for our money…

I did not want this and pushed for good design. Sharif Senbel [the architect] did a great job and we are proud of this building. Everyone admires the design and the people who originally wanted a cheap building told me ‘thank God you didn’t listen to us.’ We now have plans for expansion to do more for the community including a public library, day care, bigger MPU, classrooms, and place for play.[1]

Introduction

In many nascent Muslim communities in the north, the formation of the first mosque is typically minimal, using members’ homes and eventually converting a building. However, as communities grow, the need and desire for a purpose-built mosque becomes a clear aspiration. Construction of a new building offers opportunity to directly integrate community and cultural values in the space, yet maximum capacity is regularly prioritized over craft and design. In Prince George, located in northern British Columbia in Canada, the community opted for the route less travelled: to invest in design rather than maximum capacity. The Prince George Islamic Centre’s success within the larger community warrants observation as a study in consolidating craft and prayer within the design of the building. The approach of the Vancouver based architect, Sharif Senbel of Studio Senbel, architecture + design, focused on a conscientious use of local materials and architectural idiom, coupled with contemporary use of epigraphy, geometry, and arabesque. Through the integration of craft, as a practice of making and a consideration of materiality, several symbolic gestures toward both traditional iconography and the context of the north merge to form an engaging space for the community and a well-designed place of worship.

Craft of Prayer in Historical Mosques

Historically, embellishment of mosques centred on three motifs: epigraphy, geometry, and arabesque. Epigraphy, the large script of the sacred word of God, often quotes from the Quran, was emblazoned on mosques in key locations such as the entry portal and in the mihrab. Geometric ornament was evident at every scale, from furniture and rugs to carved star motifs on portals, and in the qibla wall. Finally, arabesque, the patterned depiction of vegetal motifs, was a clear reference to the abundant vegetation associated with paradise, and would be found predominantly in the mihrab, the virtual axis to Mecca, as well as in furniture elements.

Joint use of these motifs articulated central Islamic notions of tawhid, the indivisibility and oneness of God. The sincerity of worship, itqan, is paralleled in the quality of work undertaken for the sake of God and is considered in Islamic philosophy an integral form of dedication. Thus, design, craft and prayer are united to evoke a sense of spirituality and therein connecting the practitioner with their space of worship.

Prayer in a Small Northern Community

The small city of Prince George in northern British Columbia has witnessed a growing population of Muslims since the 1990s, who united to form a chapter of the British Columbia Muslim Association (BCMA) in 1995. For decades, the community utilized a variety of spaces for worship, including rooms at the University of Northern British Columbia, Immigrant and Multicultural Services, and the United Knox Church. In 2005, the community raised funds[2] to purchase a 3.8acre plot of land, and construction of the Prince George Islamic Centre (PGIC) was completed in 2011.

Context and Design

Senbel’s approach for the design of the PGIC began with a careful consideration of the context in terms of orientation, use of materials and environmental sustainability.

The siting of PGIC focused on a reconciliation between an orientation to Mecca, the city grid, and framing the forest escarpment surrounding the site (Fig.1). This is evidenced in “the dynamic roof forms [which are] created by the intersection of geometries between the orthogonal Prince George city grid, and the axis to Mecca (N156.5E), to which Muslim prayer spaces align.”[3]

The material palette of the building further situates the mosque within its geographic location. Spruce Pine glulam beams featured in the design, serve as structural and aesthetic elements and link the building to Prince George’s forestry dominated economy.[4] Other materials commonly used in the city are translated into the building, including an exterior cladding of bright corrugated metal (Fig. 2). The use of locally based trades embeds local knowledge, craft, and methods of construction within the design of the mosque. For example, the fabrication of the fibre glass dome placed on top of the ventilation stack tower, was produced by John Booth, a boat builder from Victoria, B.C.[5] Although known for their production of nautical equipment, insight in fibreglass construction was adapted effectively to produce a key piece of the PGIC.[6] The design additionally incorporates several environmentally sustainable strategies such as natural ventilation, on-site storm water management, and energy-efficient fixtures and equipment.

Having designed several mosques in Canada prior to PGIC, Senbel’s design approach is increasingly focussed on these elements, and is paralleled by his focus to procure and ensure quality of craft in the realization of the design.

Figure 1. Site Plan of Prince George Islamic Centre, noting the relationship of the orientation to Mecca, with the city grid and the forested escarpment. Drawing by authors.

Figure 2. Exterior of Prince George Islamic Centre located near the escarpment surrounding the city. Photograph by author, December, 2016.

An Argument for Craft

Senbel’s commitment to using local craftsmen in the design of the PGIC strengthens the relationship between the Muslim community, and the design of their cultural space. The unity of both traditional and local embellishment fosters a sense of place that is intrinsically familiar, through its iconography, to both the Muslim and larger community of Prince George. Contemporary exploration of craft in the design of the PGIC, serves to situate spirituality appropriately in the natural environment. This is reinforced by the deliberate use of glass surfaces in the design, which effectively connect the mosque to its site. By drawing natural light into the prayer space and offering views of local vegetation, these elements reinforce the central tenets of Islamic ideology.

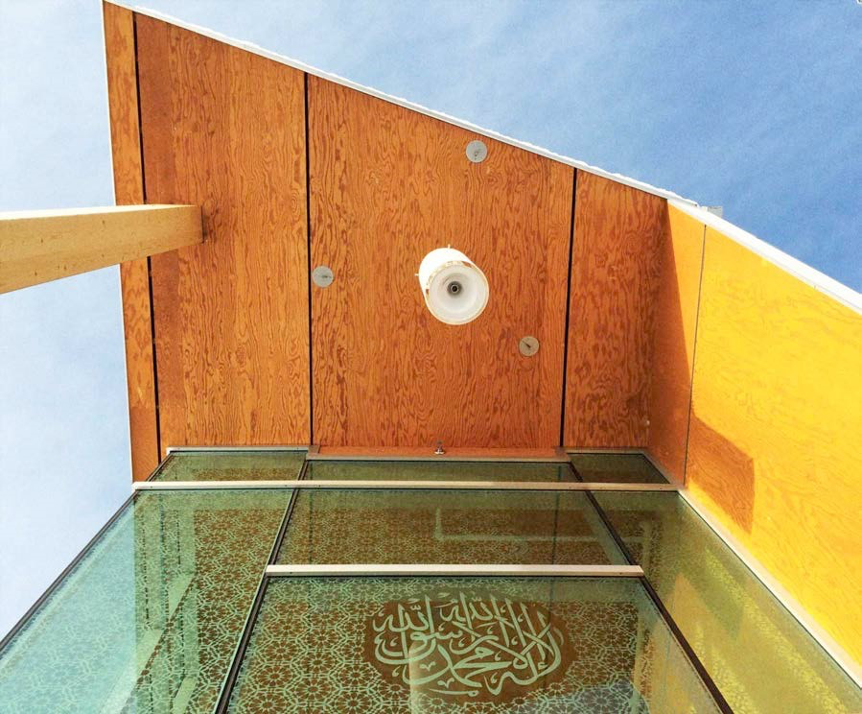

Arabic epigraphy is sandblasted on the glass surface above the main entry, and alludes to the religious function of the building. The effectively succinct text selected for the medallion shaped epigraphy is the Shahada, the declaration of faith: “There is no God but God and Muhammed is his Messenger.”[7] In crossing the threshold of the mosque, one is reminded of the most essential text needed for faith; reinforcing and emphasizing this message of light, as it is etched onto transparent glass (Fig. 3).

Twelve point stars, one of the most common geometries used in Islamic embellishment, composes the geometry surrounding the text. It is of moderate complexity, and lends itself easily to grid composition (Fig. 3).8 The etched stars read white within the transparency, effectively capturing the geometries of the natural world, which Muslims believe to be the perfect work of God.9 In this case, the white star patterns are evocative of snow falling on the house of community and prayer, a common sight for this northern city. Sandblasting the entry portal thus serves to consolidate contemporary practice with semantic consequence. Senbel worked with the glass etcher, Class Glass, based in Abbotsford B.C., and has worked with them for all his mosques with art glass. The company consistently expresses a pride of place and care in the quality of their work, illustrated by the clarity of the epigraphy found in the PGIC.10

A similar approach to design is used, in regards to establishing iconography in the qibla wall. Historically, the mihrab niche in the qibla wall was emphasized with arabesque patterns drawing on themes from local vegetal species, indicating a paradise which lay beyond the metaphysical portal of the mihrab.11 At PGIC, however, in a largely unprecedented design move, the mihrab is left nearly completely transparent, capturing the special northern paradisiac qualities of the site. The absence of classical embellishment is a distinct design decision, which both acknowledges the mosque’s relation to site and emphasizes the contemplation of God’s creation in all seasons (Fig. 4)

Berchem, M. “The Mosaics of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem” in Early Muslim Architecture (New York: Hacker Publishing, 1979) 213-307.

- Broug, Eric. Islamic Geometric Design.

- Abbas, Syed Jan and Amer Shaker Salman. Symmetries of Islamic Geometrical Patterns. Critchlow, Keith. Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmological Approach.

- “Class Glass Quality Stained Glass Products,” Class Glass, accessed April 22, 2017, http://www.classglass.ca/

- Currim, Mumtaz. Jannat, Paradise in Islamic Art.

Figure 3. Detail of epigraphy and geometry sandblasted on glass above entry portal. Photograph by author, December 2016.

Figure 4. Detail of mihrab, and qibla wall which orients the space to Mecca. Photograph by author, December, 2016.

Conclusion: Landmark and Identity

The craft of the design has enhanced and supported the activities of the PGIC. Specifically, the contemporary use of epigraphy, geometry, and arabesque grounds the mosque appropriately within its geographic location, framing Muslim identity in a northern Canadian context. The siting of the building, as well as a use of local materials, has cultivated an important sense of ownership of the mosque by the local community. This is reflected in the level of care, maintenance, and pride the community has, sharing the building with the larger community through outreach activities and hosting events throughout the year: “a mosque is not just a place where we can get together as a community; it is where we welcome other communities.”[8] In this way, the PGIC serves to promote greater understanding between Muslims and non-Muslims. The centre is a distinct building in the community –exemplar in the cooperative effort of the client and the architect– in designing a contemporary and local interpretation of Muslim space in the north.

References

Abbas, Syed Jan and Amer Shaker Salman. Symmetries of Islamic Geometrical Patterns. (World Scientific Pubishing Company, 2004).

Broug, Eric. Islamic Geometric Design. (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2013).

Creswell, K.A.C. Early Muslim Architecture Volume I Part I & II The Umayyads. (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1979).

Critchlow, Keith. Islamic Patterns: An analytical and Cosmological Approach. (Inner Traditions, 1999).

Currim, Mumtaz. Jannat, Paradise in Islamic Art. (Mumbai: Marg Foundation, 2012).

Gautier-Van Berchem, M. “The Mosaics of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem” in Early Muslim Architecture. (New York: Hacker Publishing, 1979). pg 213-307.

Mohammed, Moustafa. Interview by author. Prince George, December 18, 2015.

Senbel, Sharif. Interview by author. Vancouver, December 16, 2015.

Senbel, Sharif. Email Interview with author. January 4, 2017.

The Sublime Quran. English Translation. Laleh Bakhtiar, Trans. (Chicago: Library Islam, 2006).

Welcome to the Prince George Islamic Centre. Brochure c. 2015.

[1] Moustafa Mohammed, Chair of PGIC for over twenty years, interview with author, December 18, 2015.

[2] This was followed by support from the BCMA with a line of credit to secure the remaining required funds.

[3] ‘Building Design’ Welcome to the Prince George Islamic Centre. Brochure c.2015.

[4] Fabricated by Edmonton-based manufacturer Western Archrib, the beams utilize “beetle-kill” wood in response to the effect the Mountain Pine Beetle has had to the region.

[5] Sharif Senbel of Studio Senbel Architecture + Design, Architect, email interview to author, January 4, 2017.

[6] “Booth Enterprises: Made in Canada,” Booth Enterprises, accessed April 22, 2017, http://www.boothboats.com/

[7] The Shahada is composed of two separate references in the Quran: 3:18 ‘I bear witness there is no God but He…’ and 63:1 ‘Muhammed is the messenger.’ The combination of these two affirmations appeared for the first time as epigraphy on the Dome of the Rock in 692 CE. See the pioneering study by Gautier-Van

[8] “Mosque drawing Muslims to Prince George,” CBC News, March 16, 2010.