Gary J. Coates

Kansas State University, Department of Architecture, Manhattan, KS 66506 gcoates@ksu.edu

Figure 1: Adi Da Samraj, 2006

Introduction

Artist, author and spiritual teacher Adi Da Samraj (1939-2008) observed that “in the ‘modernist’ tradition of the early 20th century, a new, and, potentially, sacred, art emerged as a possibility—an art of profundity, free of both ‘official’ religion and merely secular impulses”.1 Yet, because of the process of civilizational collapse that was brought on by two World Wars and a global depression, he also noted that the liberatory potential of this artistic revolution was never able to come to fruition.2 Only now, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, did Adi Da believe that it was possible and, indeed, urgently necessary for the “emergence of a new order of both civilization and culture—and, thus, for the emergence of a new, and truly sacred (non-religious, non-secular, and Really non-egoic), art.”3

For more than four decades Adi Da labored to create such a transformational art, experimenting with a variety of media and modes of expression.4 In all of this work he sought to create forms of art that would draw the fully participatory viewer into the inherently blissful state of nondual awareness that he asserted naturally arises once we transcend the sense of being a separate “self” confronting a separate (and thus inherently threatening) “world”. To make such an experience of “aesthetic ecstasy” possible he formed each image to be the “Inherently egoless (or ‘point of view’-less) Direct Self-Presentation of Reality Itself,”5 which he describes as being entirely “Non-separate, One and Indivisible.”6

Adi Da described the “aperspectival, anegoic, and aniconic”7 images he created with digital means between 2006 and 2008 as being not only the final resolution of his own lifelong work as a visual artist, but also as the fulfillment of the spiritual impulse that was only implicit in the abstract images of such early twentieth century artists as Kandinsky, Malevich and Mondrian, i.e., the creation of an art that would enable the viewer to be completely liberated, if only for a moment, from the binding limits of “point of view” itself.8

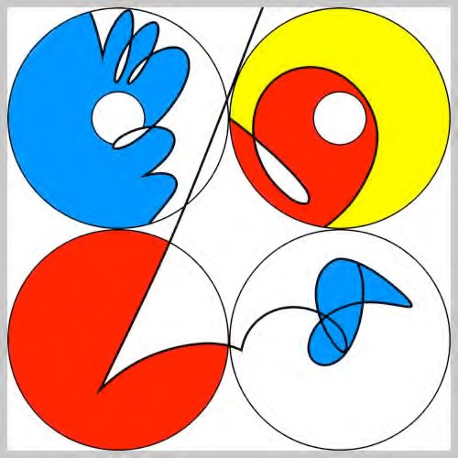

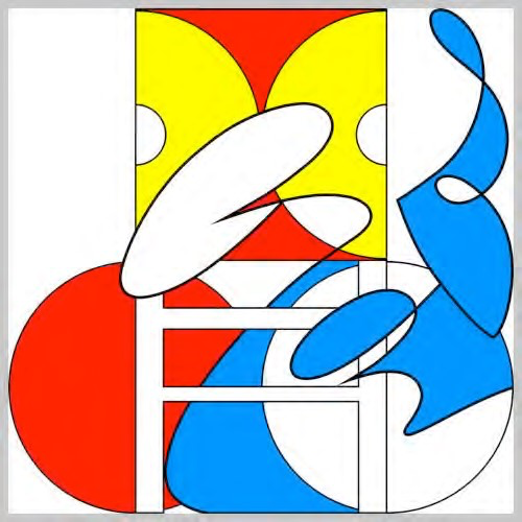

Figure 2: Eurydice One: The Illusory Fall of The Bicycle

Into The Sub-Atomic Parallel Worlds of Primary Color and Point of View—

Part Three: The Abstract Narrative in Geome and Linead

(Second Stage)—1, 2 (first panel),from Linead One,2007, 2010 Lacquer on aluminum, 96 x 96 inches / 244 x 244 cm

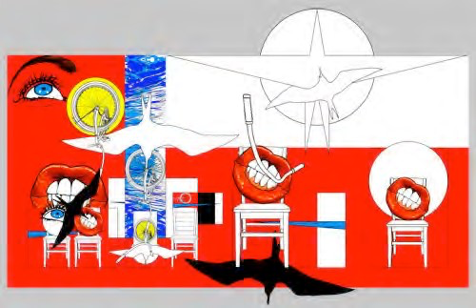

Figure 3: Adi Da Samraj: Orpheus and Linead, exhibition at the Sundaram

Tagore Gallery, New York City, September 9-October 9, 2010

Form and Meaning in the Orpheus and Linead Suites (2007)

From September 9–October 9, 2010, an exhibition entitled Adi Da Samraj: Orpheus and Linead, was held at the Sundaram Tagore Gallery in New York City featuring eleven monumental abstract images created by the artist in 2007.9 As re-interpreted by Adi Da, the essential story underlying these suites is the tale of a heroic being from the world of light, Orpheus, who descends into the world of darkness and death in order to bring his beloved wife, Eurydice, back to the world of light and life. Unlike the mythical Orpheus, however, who looked back before Eurydice was fully emerged from the underworld, thereby losing her forever, Adi Da’s Orpheus never looks back and thus succeeds in bringing his beloved back with him to the world of light.10 Thus, Adi Da’s version of the story is a divine comedy rather than an archetypal human tragedy.

Figure 4: The Spiritual Descent of The Bicycle Becomes The

Second-Birth of Flight: Part Six—II, from Orpheus One, 2007

Figure 5: The Spiritual Descent of The Bicycle Becomes The Second-Birth of Flight: Part Six—VII, from Orpheus One, 2007

The process by which Adi Da composed these suites reveals much about how he worked to integrate form and meaning in all of his artistic images. As can be seen in Figures 4 and 5, he began by taking photographs of natural forms–a chair, a bicycle, female subjects and a bird in flight–in direct response to his own radical re-imagining of the Orpheus myth.11 He next composed these images into digital “sketches”, and proceeded to abstract each of them using a visual language made up of: the primary colors, as well as black and white; “Geomes” (the primary geometries–squares, circles and triangles); and “Lineads” (free flowing hand-drawn lines he made for each suite).12 As a result of this iterative process of ever-increasing abstraction, each successive image became the basis for the next one, until the final image became “utterly free in and as itself—independent of memory and the conventions of ordinary perception.”13

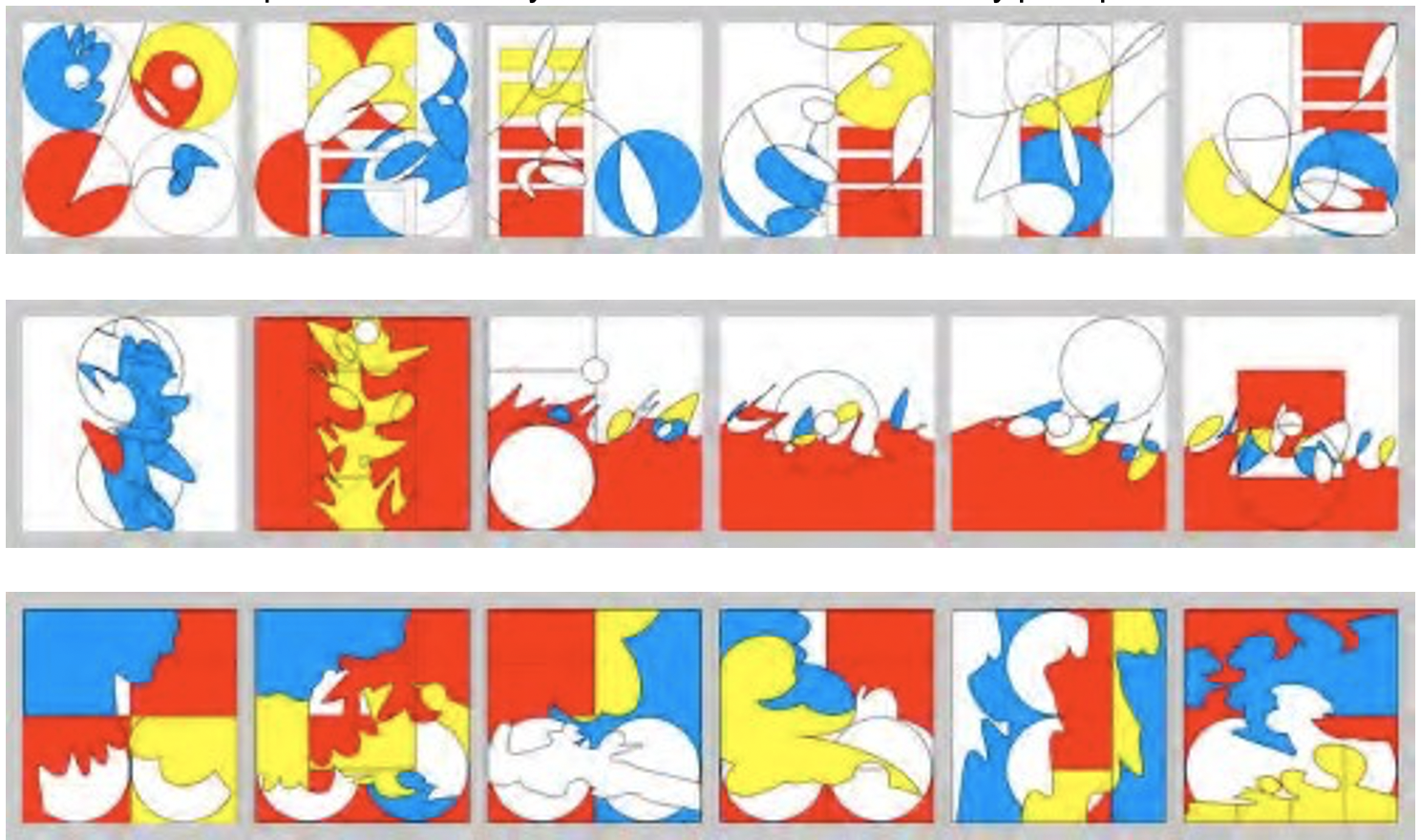

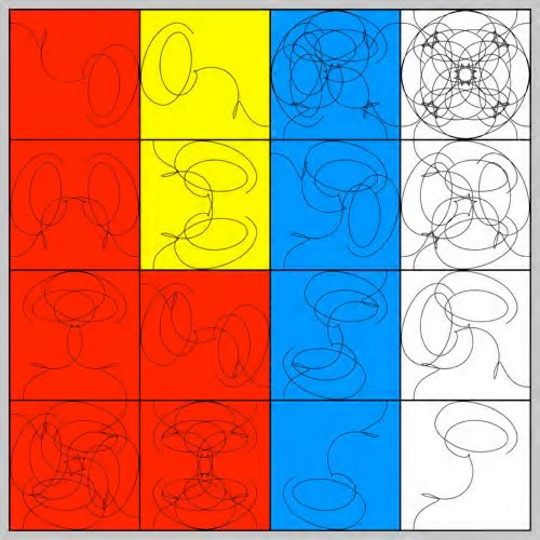

Figures 6, 7& 8: Eurydice One: The Illusory Fall of The Bicycle Into The Sub-Atomic Parallel Worlds of Primary Color and Point of View—Part Three: The Abstract Narrative in Geome and Linead (Second Stage), (I, 2), (I, 4) and (I, 5) respectively, from Linead One, 2007

According to Adi Da, his use of pure abstraction in these suites (or any others) did not mean that his images were without meaning. Indeed, as he repeatedly stated, “Art is meaning…Meaning is the discipline of art.”14 Adi Da’s artistic meanings, however, are expressed in varied ways and at a number of different levels, as can be understood even by a brief consideration of three sets of six images from the Linead One suite, each of which, when read from left to right, recounts Adi Da’s version of the Orpheus myth. In all of the first panels, it is possible to discern the presence of an abstract male figure (Orpheus) appearing in the realm of light with his bicycle ready to descend into Hades, while in all the second panels a similarly abstract female figure (Eurydice) can be seen to be present, apparently entangled in the rungs of a ladder in the yellow-red realm. 15

In the final four panels of each series, the seemingly failed attempt of Orpheus to bring Eurydice out of darkness into light, as recounted in the traditional narrative, unfolds as a rising and falling motion of these two figures. “In the end, however, and in the last image, all apparent difference (and all ‘point of view’) is seen to be illusory, although all appearances still register as red, yellow, blue, white, and black.”16 Thus, in the final images of Figures 6, 7 and 8 it can be seen that there is no realm either high or low that is bereft of transcendental light.

In all three sets of six images, Adi Da Samraj has created an “abstract narrative,” a brightly illumined non-representational visual world that does not so much tell a story as it generates “a field of meaning that coincides with the essential meaning of the myth, as re-imagined by Adi Da.”17 The ultimate meaning of these images and all of Adi Da Samraj’s art, however, is never to be found at the level of the conceptual mind, literary narrative, or any apparently recognizable forms.

Figure 9: Eurydice One: The Illusory Fall of The Bicycle

Into The Sub-Atomic Parallel Worlds of Primary Color and Point Of View:

Part Three: The Abstract Narrative in Geome and Linead

(Second Stage)—I, 2 (second panel), from Linead One, 2007, 2008Lacquer on aluminum, 96 x 96 inches / 244 x 244 cm

When experienced as he intended, the true “meaning-force” of all of his images is non-verbal and paradoxical, existing “between and beyond both representation and abstraction.”18 This final, tacitly felt level of meaning only arises, however, when “the ‘point of view’-made and intrinsically ego-bound abstractions that comprise ordinary perception” are rendered back to the “egoless Reality-Source” within which all perception mysteriously arises.19 This timeless moment of

“aesthetic ecstasy” is what Adi Da Samraj calls the “ego-transcending process of Perfect Abstraction.”20

Figure 10: The Spiritual Descent of The Bicycle Becomes The

Second-Birth of Flight: Part Twelve—II, 4, from Orpheus One, 2007, 2010 Lacquer on aluminum, 60 x 60 inches / 152 x 152 cm

Endnotes

- Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental Realism: The Image-Art of egoless Coincidence With Reality Itself, 2nd ed. (Middletown, CA: The Dawn Horse Press, 2010), 167.

- Ibid., 163.

- Ibid., 167. 4 Mei-Ling Israel, The World As Light: An Introduction to the Art of Adi Da Samraj, (Middletown, CA: The Dawn Horse Press, 2007). See also Gary J. Coates, “The Rebirth of Sacred Art: Reflections on the Aperspectival Geometric Art of Adi Da Samraj,” at www.daplastique.com. This site also has essays by other critics as well as a large selection of Adi Da’s art.

- Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental Realism, 32.

- Adi Da Samraj, Perfect Philosophy: The Radical Way of No-Ideas (Middletown, CA: The Dawn Horse Press, 2007), 40.

- The three interrelated terms “aperspectival, anegoic and aniconic” were coined by Adi Da to describe his abstract images and the image-making process by which they were made. By “aperspectival” he meant that his images were not created from any space-time located “point of view” using the methods of linear geometric perspective. By “aniconic” he meant to say that in these images there are no visual references to any separate “icon”, or “objectified subject”, as it might be “seen” from any separate “point of view”. By the term “anegoic” he was proposing that his images are not “ego-based or ego-useful” because they were created by means of a systematic process of abstraction that “intrinsically transcends the ‘point-of-view’-orientation of the perceiving body.” For a more complete explanation see, Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental Realism, op. cit. 49-66.

- Ibid.,, 49–66.

- This exhibition was curated by the renowned Italian author and art critic Achille Bonito Oliva. See www.sundaramtagore.com.

- Adi Da Samraj: Orpheus and Linead, exhibition catalog (New York: Sundaram Tagore Gallery, 2010), 10. 11 In Figures 4 and 5, which flow from left to right, there is a movement down from the world of light into the yellow-red realm of Hades and then up again into the world of light (the two birds flying into the circle of Transcendental or Divine Light). This same abstract narrative and rising and falling movement also can be seen in Figure 10, which is reminiscent of a 4 x 4 Indian Yantra, or sacred diagram. In this image the play of Lineads as they fall and rise within this sacred enclosure (Temenos) culminates in a beautiful geometric mandala which emerges within the field of light located in the top right square.

- Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental Realism, 44.

- Ibid. 14 Mei-Ling Israel, The World As Light, 23.

- There is some history and humor here. It will remembered that the Wright brothers were bicycle mechanics and that the seat on their flying machine was a bicycle seat, suggesting that Adi Da’s abstract bicycle could, in fact, also be an instrument of upward flight.

- Adi Da Samraj, “Linead One (Eurydice One): The Illusory Fall of The Bicycle Into The SubAtomic Parallel Worlds of Primary Color and Point of View,” unpublished art commentaries.

- Adi Da Samraj: Orpheus and Linead, 10.

- Ibid. 19 Adi Da Samraj, Transcendental Realism, 110.

20 Ibid.

All images and photographs copyright © 2010 by the Avataric Samrajya of Adidam Pty Ltd, as trustee for The Avataric Samrajya of Adidam. All rights reserved. Perpetual copyright claimed.