Clive Knights

Portland State University, Portland, Oregon

knightsc@pdx.edu

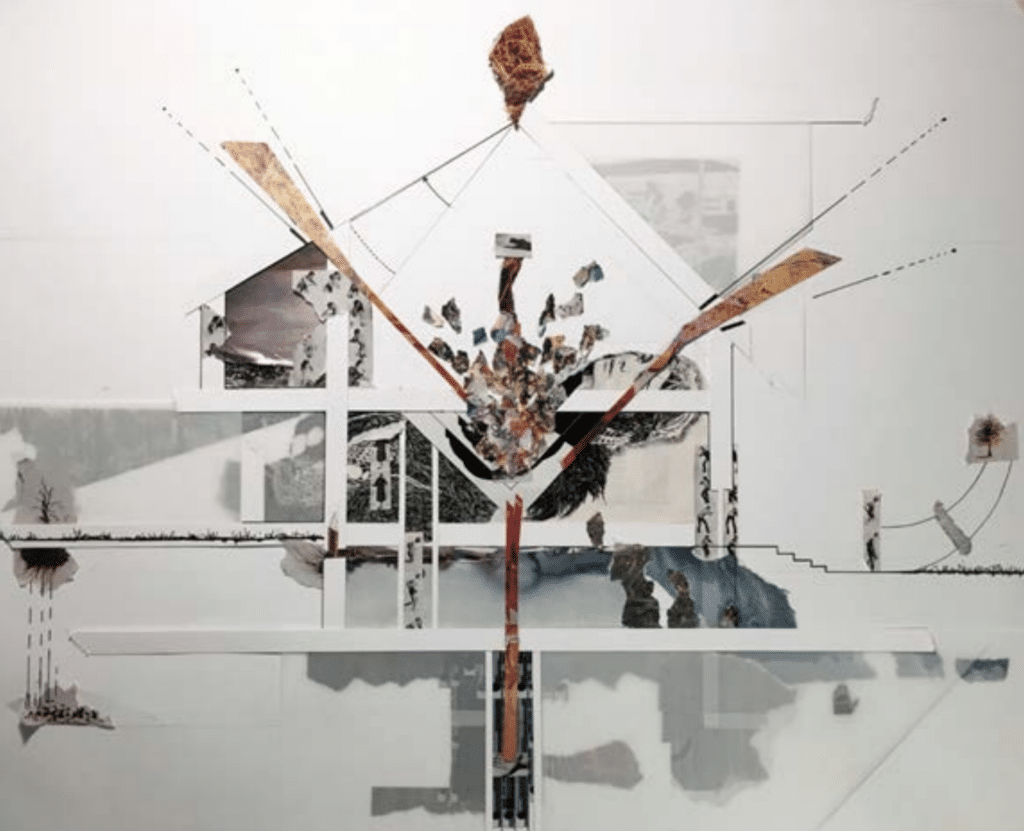

Figure 1: Collage section study of an existing home reconnecting with its natural setting (photo credit Xander Sligh)

“Meaning depends on the continuity of communicative movement between individual elements and on their relation to the pre-existing latent world. The continuity of communicative movement manifests itself in the legibility of concrete architectural space in the same way as it does in a poem or a collage.”

— Dalibor Vesely

The late architectural theorist, Dalibor Vesely, in his book Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation, references what he calls the ”restorative role of the fragment” in creative practice. The apparent fragmentation of the contemporary world, he suggests, is manifest as so many isolated forms of specialist knowledge dislocated from a common, latent background, what he calls the primary or natural reality. The necessity in scientific research, for instance, to control the process of experimentation, observation, and verification, requires the encircling of its content to remove it from a broader lived reality into the controlled environment of the laboratory. The result is the conception of a positivist world built from separate, empirically clarified components joined by explicit logic. The specialisms that abound in contemporary architectural practice exert much the same impediment upon the possibility of communicative continuity across the diverse and multiple levels of lived reality. By the extensive research of the phenomenological tradition, in particular the work of Merleau-Ponty, we are reminded that within lived experience our bodies precede our thinking selves, that the sensorial body pieces together partial perceptions bound by shifting, overlapping horizons, that imply a primordial whole without ever offering it up in its totality. These partial perceptions are a different kind of fragment with a synecdochical capacity to imply the fully present but never fully disclosed whole, a shared cosmos which surpasses each individual human life while informing and structuring the possibilities of each.

Linda Nochlin, in her book The Body in Pieces, identifies 18th century revolutionary dismemberment as an emblem of transformation and release from the dictates of monarchical and therefore religious hegemony, a symbolic ‘breaking apart’ that has its origins in earlier forms of iconoclasm; shattering a cultural whole into fragments, out of the debris of which the possibility of a new and differently comprised unity might arise. A fragment can be seen as evidence of a previous, complete thing now broken into pieces, a fragment ‘on its way from,’ so to speak.

Alternatively, a fragment can be understood as a part of something incomplete, yet to be completed, a fragment ‘on its way to.’ The deftness of the collagist is to be able to enact the transformation of the fragment in either direction. The dismantling of books and magazines, of previous wholes issued by the machinations of popular culture can be seen, perhaps, as a form of contemporary iconoclasm, challenging preset meanings embedded in the iconography of printed media. The acts of cutting, ripping, tearing, splicing, displacing, removing, and re- assembling are minor revolutionary acts in themselves, performed within the reach of the hands and the purview of the eye. But then, like the quarry of archeologists, these multiple fragments of previously manufactured artifacts, once released from the fixity of the medium in which they have been buried, hold the potential to speak of imagined worlds, re-enacted in terms of human lives and their unfolding.

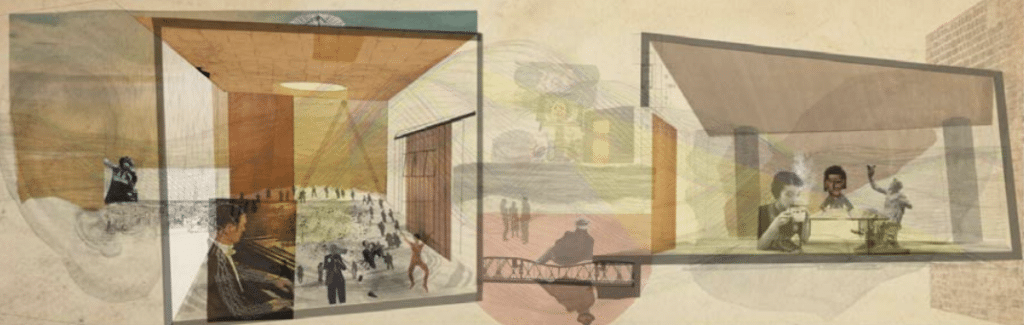

Exploring the handmade and digital collages created by graduate architecture students in the architectural design studio, this project reveals the efficacy of handmade collage work as progenitor in exploring the cultivation of human community in a context of natural cycles.

Addressing themes of human necessity such as feeding, sleeping, washing and congregating, one project challenges the commodified, introspective spatial realities of an existing contemporary home by effectively turning it inside out to respond to its broader urban and cosmic context. The second project addresses mental health in the houseless population and deploys collage to uncover the commonalities of an otherwise displaced community and to inspire the design of new settings for communal experience in the diverse and fractured contemporary city.

References

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962

Nochlin, Linda. The Body in Pieces. London: Thames & Hudson, 1994

Vesely, Dalibor. Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation. Cambridge: MIT, 2004

Figure 2: Collage study of communal settings for playing music together (left) and dining together (right)

(photo credit Justin Tuttle)