Julia W. Robinson2

School of Architecture, University of Minnesota

robin003@umn.edu

Community Engagement & the Design Studio: Communion by Doing1

Abstract

Communion: “the act of sharing one’s thoughts and emotions with another or others”.3 (Collins, 2023)

Focusing on empowerment of community members as collaborative or co-designers, this paper explores the interactions that lead to a communion between steward- designers and community participants. This project strives for leadership by the community, and listening and designing together. Thus, students and interns are stewards of their projects rather than having ownership. Additionally, the class methods encourage community members to tell their experiences in relationship to their neighborhood.

Co-Design in North Minneapolis

The Minneapolis murder of George Floyd revealed the insidious role of systemic racism, where redlining and racially restrictive deeds were followed by years of disinvestment in predominantly Black neighborhoods like North Minneapolis. The urban planning processes that created a great racial and economic divide in the city remain unquestioned.

This project seeks to address the planning system, by awareness of the structures that inflict bias, and developing alternatives to the typical processes. McKercher notes that “traditionally, design control is held by the city and the city planner.”4 In her view, community co-design “an approach to designing with, not for, people.” includes four key attributes that our project adheres to: sharing power, prioritizing relationships, “moving people from participants to active partners” and building capability.5

This requires informed decision-making from neighborhoods. Three of Hasselaar’s five levels of participation engage community: consulting, participating, and decision-making. 6 In our first year, our project was more consulting. But starting in 2022, we are employing co-design or collaborative/participatory design that includes community expertise in design decision-making.

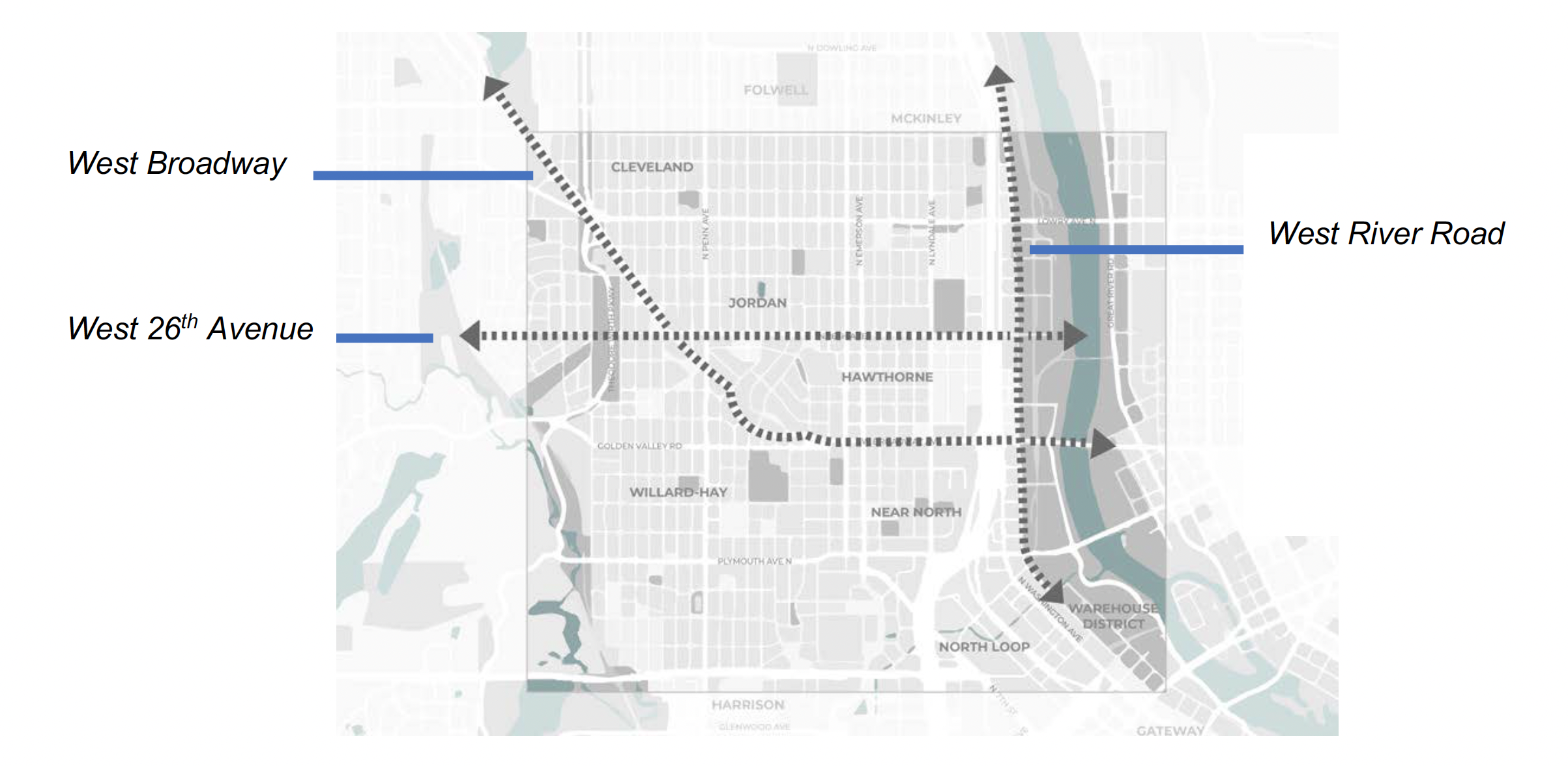

The project focuses on North Minneapolis, including West 26th Ave, which potentially links the Minneapolis Park System to both the Mississippi River and West River Road, by reconnecting the neighborhood to the river across the I-94 highway that separates the largely residential neighborhood, from the industrialized and polluting river area (see Illustration 1). We also include Neighborhood West Broadway Avenue, the business corridor, which creates a triangular focus area within the neighborhood.

Illustration 1. The Project Site in North Minneapolis (Map by Julia Friedrichsen)

Our Investing in/with North Minneapolis project precedes the city process aiming for control by the neighborhood, in terms of both design and implementation. We seek plans that are so well designed, compelling and implementable that neighborhood political support will assure they are built.

Evolving Approach

In 2021, the program sought a shared urban design using Geodesign.7 Meeting over Zoom due to COVID thwarted interactive design, resulted in a consultative rather than co-designed project.

Furthermore, maps and axonometric drawings that showed urban design options were rejected by participants as being patronizing and disempowering.

In 2022, eight youth interns joined the work, sharing expertise on sustainability, and neighborhood experiences. The university students included interns as project co-stewards. The urban design phase focused on specific issues rather than comprehensive design, leading to architectural projects co-designed with the community in reviews and co-design events. At these events, students and interns used questionnaires, drawings and models, to elicit ideas.

Informal round robin reviews more successfully promoted co-designing than traditional reviews and allowed transferred of effective techniques to co-design events. As previously, community, university and city experts spoke in class. Outside of class, students volunteered, participated in community events, and interviewed community members.

Stewarded Projects

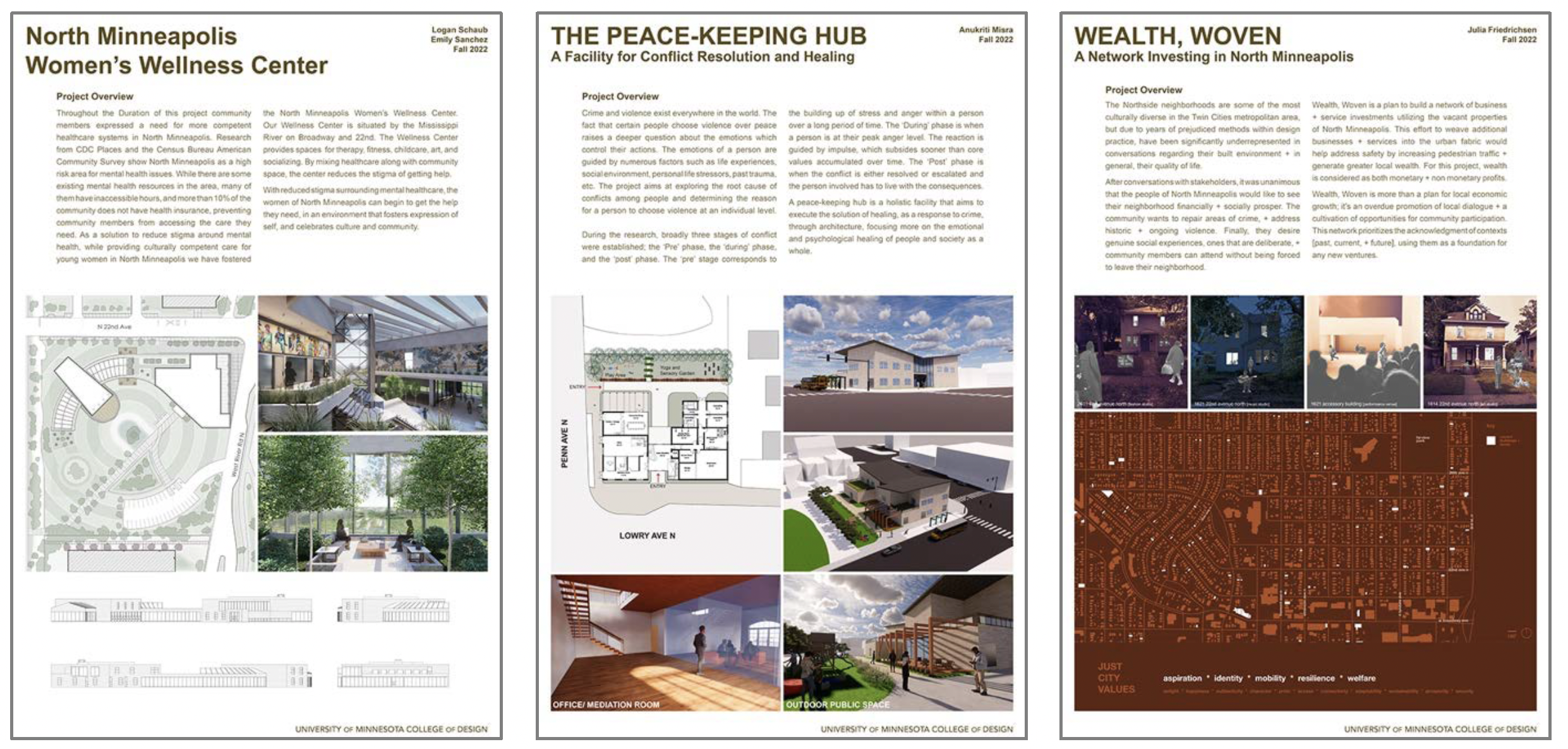

The six student designs for fall 2022 were wide-ranging in their content and approach. Students designed: mental health center for Black women (illustration 2A) reduction of street violence through peacemaking (illustration 2B); live-work businesses in vacant properties (2C); opportunities for fishing and fine eating on the river; using alleys in existing blocks to create co- housing; and renovating an abandoned school for housing and job training for youth leaving detention or foster care.

Illustration 2. Selected Projects

A- Women’s Wellness Center Logan, Emily Sanchez; B- Peace-Keeping Hub by Anukriti Misra; C- Wealth Woven Investing by Julia Friedrichsen

Evaluation & Conclusions

The approach to advancing co-design has been to learn by doing. By means of student course evaluations, and formal interviews with a small number of community participants, each year we developed and evaluated our working relationship with community members.

Participants & Community Building

Criticisms of the group of participants in 2021 led to including interns of color as well as community members and professionals in 2022. We also increased the number of instructors and project team members of color.

In 2022 we also added co-design events, invited community members to reviews, interviewed individual community members, and volunteered at community events- all to be continued next year.

Each year the project has included more people and organizations. For 2023, to meet our goal of having the project community-led, we expanded the project team, added an advisory group, and are collaborating with a Black-led neighborhood organization as fiscal agent for grants.

In-class reviews. Because informal reviews generated excellent engagement, three of our four reviews were informal round-robin reviews, where design stewards posted their work and engaged reviewers in co-design activities. These reviews were intense but very productive.(see illustration 3) The two-hour format lends itself to thoughtful feedback and storytelling about the neighborhood.

Illustration 3: Exploratory models engage discussion at a review. (Photo by Julia Robinson )

Co-design events instituted this year opened participation to the entire community. Activities included a walk-about, lunch speakers, small group meetings and mapping exercises that engaged identification and discussion of important concerns. As the six-hour co-design events proved too long, next year we will have similar activities, but in three, three-hour events.

Media– We avoided using digital drawings in early reviews and co-design events to make the presentations less finished, more informal, and less intimidating for active participation. Having a variety of materials available and students and interns ask community members to show their ideas, encouraged co-design modeling and drawing designs that advanced the project.

Our first-year discovery that the standard urban design axonometric and bird’s eye perspectives was seen as manipulative led us to focus more time on architectural design in 2022, and to build on the work of previous years’ research on North Minneapolis. In 2023, we plan to experiment with urban scale design, developing model-making, eye-level sketches and perspectives that focus on human perspective.

Story Telling– The students were inspired by the project participants’ stories, but we did not document this important information. Next year we will document stories from past years, and institute after-review, and after-co-design discussions to capture these in written form as part of our on-going research.

Communion– In 2022, community members participated significantly more than in the past, due in large part to the participation of interns of color from the community. The students, interns and community members communicated and collaborated well, especially at the informal reviews.

Also increasing our participation and visibility in the community enhanced trust in our work. While the process of our community engagement was not perfect co-design, by implementing the

concept of project stewardship, finding good media for representing ideas, participating in community events and above all, listening to the community, we advanced the approach toward true communion this year. Now we need to do a better job at recording ideas and stories.

1 This work is described in Robinson, J., Timothy Griffin, Jaycie Thomsen, Savannah L. Steele, Michael Chaney, and Jamil Ford. ”Towards a Community-Led Design Studio: Cultivating Relationships and Stewarding Projects ,” The Research-Design Interface: Proceedings of the ARCC-2023 Conference, (Dallas: Architectural Research Centers Consortium, in press).

2 This paper interprets work done between Jan 2022 and May 2023.with research colleagues cited above for the Investing in/with North Minneapolis Project. This Project was funded by the School of Architecture, the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs and the Imagine Fund all from the University of Minnesota, as well as United Properties Development and the Minneapolis Jordan Area Community Council.

3 Collins. Collins Online English Dictionary (Website 2023,) https://www.collinsdictionary.com/us/dictionary/english/communion

4 McKercher, Kelly Ann. ”What to Expect,” in Beyond Sticky Notes: Doing Co-Design for Real, (Cammeraygal Country, Australia: Inscope Books, 2020), 10.

5 Op. cit, 14-15

6 Qu, L. and E. Hasselaar. Making Room for People; Choice, Voice and Liveability in Residential Areas, (Amsterdam: Techne Press, 2011), 92.

7 Steinitz, C. A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design, (Redlands, CA: Esri Press, 2020).