Tammy Gaber

Laurentian University, Ontario, Canada

tgaber@laurentian.ca

Introduction

As a building type, the sacred space is both the container and facilitator framing transcendental or spiritual experiences. The qualities of the sacred space are choreographed, curated and crafted at all scales to emphasize and express this. The phenomenological qualities of a sacred space are directly connected to the craft of every detail, every sequence of space, every material and every governing geometric system of organization. In developing a new curriculum for a new school of architecture the author developed course content for both a first year, undergraduate, cultural history course ‘Sacred Places’ and a graduate studio on ‘Craft and the Sacred’. It was the intention of the author to bring to the fore, the open[1] and important lessons in design gained from in-depth analysis and study of existing sacred spaces, both historical and contemporary. In the graduate course, the author guided the synthesis of this material through a series of exercises that led to the design of a sacred space by each student. The undergraduate course was taught six years consecutively and the graduate studio has, to date, run for two consecutive years. The lessons in pedagogical continuity of framing an architecture education with a focus on the sacred are outlined in this paper. In both courses extensive material was drawn from both Architecture Culture Spiritual Forum archives and from Faith and Form journal archives.

Architecture of the Sacred : Undergraduate Cultural History Course

The undergraduate first year course, ‘Sacred Places’ was developed with an emphasis on phenomenological[2] and hermeneutical[3] interpretations of space as tools to connect primary sources of mythologies to physical expression in the material arts, landscape and architecture. Five to six creation myths[4] were examined each year and case studies explored in class. A field trip to regional museums and sacred places and a film series complimented the lectures, which allowed for some degree of immersion in the material directly. The primary assignment for students was the analysis of a contemporary sacred space through the construction of a 1:1 to 1:5 detail and a research paper.

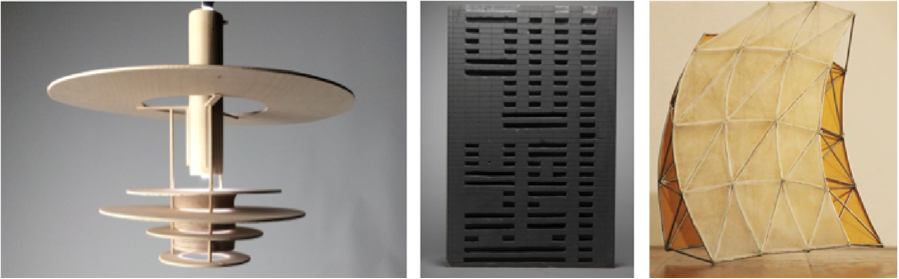

Figures 1,2,3: Details re-made by first year students in 2018: lamp (Myyrmaki church, Finland) made by Harrison Lane, brick wall (Al Irsyad mosque, Indonesia) made by Tiffany-Lynn Hodgens, glass wall system (Bahai temple, Chile) made by Liam Bursey.

The curation of this course afforded continuity not only between historical and contemporary analysis of sacred architecture design but also a continuity between subjects of cultural history and architectural design, normally segregated in architecture school.

As a foundation course, ‘Sacred Places’ subject material spanned history in a global and nonlinear manner, acknowledging the simultaneous and important works of indigenous cultures, fareast and eastern practices as well as western practices. A particular focus on the feminine with respect to the role and impact on sacred spaces was emphasized. This course was established by the author with the formation of the new school of architecture six years ago and the author has taught the course each year with modifications.

Architecture for the Sacred : Graduate Design Studio course

Two years ago the graduate school was established and the author developed curriculum for an option graduate studio ‘Craft and the Sacred’ and has taught it twice. The dual concepts of analogue and digital craft (at all scales) and designing for the sacred framed the course. In both iterations of the graduate studio the curriculum underscored research exploration through literature review, case study analysis, site visits and analysis, research-creation with the design and making of a liturgical object and synthesis through the design of space.

The first year this studio ran, the site was in Reykjavik, Iceland and the second year the site was in Helsinki, Finland. Travel to these locations was chosen as the majority of the students’ undergraduate education had focussed on the specificity of regional area of the school of architecture’s location in Canada and the students had minimal first-hand exposure to other design practices in the same latitudes. The northern locations of Reykjavik and Helsinki afforded similar lessons in climate and expanded exposure to diverse building practices. In both years the students were led by the author through a study of the site, a study of exemplar sacred spaces and visits with architects including Juhani Pallasmaa and Juha Leviska to discuss issues of design for the contemporary sacred.

Following the site visit, the design process began in the microcosm with the individual design and construction of a 1:1 or 1:5 model of a liturgical object or wall system.

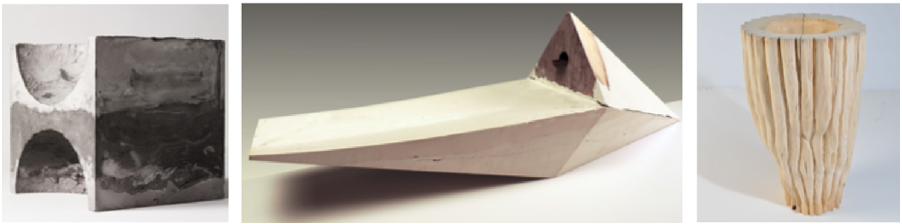

Figures 4,5,6: Liturgical object prototypes by students in 2017, 2018: Hindu temple foot-washing stool (plaster and ink) by Sahana Dharmaraj ; All-faith funerary centre body washing stand (plaster, ink, wood, copper) by Lisa Hoshowsky; Catholic church baptismal font (cedar) by Alex Klein-Gunnewick.

Students were then led in vignette exercises to design sequences of spaces with context specific references (such as orientation, views, landscape, materials) spaces in perspective and section. This was followed by design development through conventional architectural drawings and models.

Figures 7,8,9: Multimedia perspectives by students in 2017, 2018: Buddhist temple design (Reykjavik) by Shannon McMillan; Mosque design (Helsinki) by Suleman Khan, and All-Faith chapel design (Helsinki) by Marie Jankovich.

The framework of craft and the sacred in the design of a space served in continuity with material from the foundational cultural history course that also focussed on phenomenological and hermeneutical understandings of sacred spaces.

Sacred and Continuity in Pedagogy Beyond : Reflections and Potentials

Reflecting on the methodology a few reflections can be identified. The cross-pollination of making in a theory course and theory in a making course supported rich avenues for synthesis of the material. Ideally a data base of case studies identified and successfully completed could be created and utilized by both the first year theory course and the graduate studio course with accumulated primary research documentation such as the on-site photography and drawings as well as the explorations.

Pedagogically, it would be beneficial to have both of these courses taught in the same semester, currently they are not. The potentials of mentorship and support from graduate students could come in the form of Teaching Assistantships but also younger students seeking further insight would gain knowledge from participating actively or passively in the process of the graduate work by attending reviews and/or helping the graduate students during deadlines. The graduate students expressed to me directly their desire to ‘retake’ the first year theory course, in order to sit in an reflect again on the content holistically as it is curated by the framework of ‘Sacred Places’.

The successful outcome of the courses developed have periodically been shared in School-wide exhibitions. However, a concentrated exhibition of the process and final works from both courses would be of great benefit to the culture evolving at our new school. Currently the author is developing, with a graduate student, a book documenting the travels, process and final works of the courses which will be published for dissemination at the school.

The students who completed this option graduate studio gained a range design and research techniques and methods allowing for transition into the next phase of their education, their independent thesis. Student’s individual agency in the process challenged their design skills and their ability to synthesize complex theoretical and theological material into relevant and contextual design – lessons that will ideally endure.

[1] Following the idea of a constantly interpretive creative work as outlined by: Eco, Umberto. The Open Work. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989.

[2] Required readings for the course from: Pallasmaa, Juhani. Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. New York: Wiley, 2012. And Barrie, Thomas. The Sacred In-Between The Mediating Roles of Architecture. New York: Routledge, 2010.

[3] Jones, Lindsay. The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture Experience, Interpretation, Comparison.

Volume One Monumental Occasions Reflections on the Eventfulness of Religious Architecture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

[4] The course has in the past covered material from Ojibwe, Inuvaluit, Pueblo First Nations; Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead; Ovid’s Metamorphosis and Vergil’s Aeneid; Agganna Sutta; Kojiki texts; Old Testament; New Testament; Quran.