Robert Hermanson

University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah

xtreborx@comcast.net

Continuo

What is Continuo? [1] In Baroque music it serves as an accompanying part of the musical score with a bass line and harmonies, usually played on a keyboard instrument. Its purpose is to indeed serve as an accompaniment… a form of the continuation of the music as the major instruments (or voice) perform their roles.

This notion of an accompaniment, a support to the major role of the work is observed throughout history in several disciplines. For instance, in film, the use of “temporal” continuity vs. “spatial” continuity is used to convey either time, or spatial notions.[2] In such instances, the editing process presents itself, as a kind of accompaniment, the Continuo to the original narrative. But film is also about time, through motion. It is diachronic. As such it provides both the actuality of a moment, but also memories via flashbacks, or anticipations, via flash forwards. Consequently, the original narrative itself, becomes the Continuo… the continuity in the drama that is nevertheless unfolding, which is all about change. A great example is found in the film directed by Orson Welles, “Citizen Kane.” In the film, Kane is the protagonist who dies, yet whose life remains an enigma of complex conditions. These are attempted to be made visible through a series of “flashbacks”, interviews with those who had known the man. The continuo, the sustaining bass remains Kane himself, while the changes through the interviews are in what Roger Ebert called “an emotional chronology set free from time.”[3]

Pictured: Citizen Kane

Architecture is a synchronic discipline… frozen moments in time and materiality. But it involves multiple conditions. Like film, with its editing processes, architecture requires firstly, a site that itself becomes an edited place…. it changes. In the modernist movement, setting and site were diminished. Le Corbusier had his villas such as the Villa Schwob set in pristine settings, even airbrushing out in photographs, the surrounding environmental scenes… with little or no reference to the actual sites themselves.[4] History… and the site, in other words, were obliterated! But not quite. Rather than having a surrounding environment devoted to nature, he situated nature on the rooftop of the Villa Schwob[5]… in other words a displacement had taken place. So both the site itself, the building, and nature were all participants in the notion of change. If there was continuo regarding the site, and nature, it was dramatically altered.

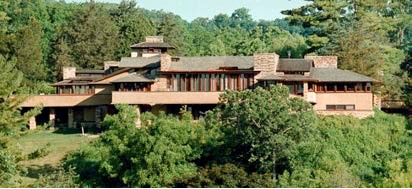

But what is the site really all about? Wright once said, upon establishing his location for Taliesin (in Welsh, “Shining Brow”) that it should not be at the top of the hill that he had chosen, but rather on its brow. Otherwise, as he so succinctly observed, the hill would be lost.[6] In this act, Wright conveyed a notion of the continuity of nature that embraced his philosophy of architectureand its relationship to the world around it. But, it also conveyed the notion of an accompaniment to nature that here became the Continuo to the major voices of the building itself. The land formed the constant… the architecture the change. Likewise, at “Fallingwater” the site is dominated by the waterfall which Wright nevertheless maintained, but by building over what Edgar Kaufman had often enjoyed as a place to relax and even bathe in[7] Here, as at Taliesin, continuo and change merge. What are seemingly opposites, become mutually integrated.

Pictured: Taliesin East

Heraclitus acknowledged conditions of opposition. His understanding of the relation of opposites to each other enabled him to overcome the chaotic and divergent natures of the world, and he asserted that the world exists, interestingly, as ultimately a coherent system in which a change in one direction is balanced by a corresponding change in another… in other words the unity of opposites.[8] Thus, his famous observation that one cannot enter the same river twice.

Consequently, change is ever present… but so is continuity. Soraj Hongladarom observes that “A changing object can be continued also, in roughly the same sense as we say that an event, like a drama, continues even though everything in it is changing.[9]

I would argue that Heraclitus’ notion of constant change, vs. the accompaniment of a thing, its Continuo, suggests a profound aspect of the present cultural condition…. and a resistance to the world now surrounding us. In an essay entitled “End the Innovation Obsession” David Sax observes that we have become obsessed with the ever present “new” in constant pursuit of the innovative.10 He comments on the simple experience of a library in a park in Seoul, Korea, as being an innovative event! It has books, a café, and above all, the solace of being able to read an actual book in a garden. There are no digital screens, not even Wi Fi! In other words, it is not a Silicon Valley transplant! The truly innovative is not about the latest technological expressions of our supremacy, but rather a reconnection with the world around us… a phenomenological condition that also requires the necessity to pause.

Caesura

In music there is a term for the pause… “Caesura”. It is defined as “a break in a verse where one phrase ends and the following phrase begins.11 It’s time frame may vary, from a few moments ( one taking a breath, while singing or playing an instrument) to extended conditions…perhaps the end of a movement, such as Handel’s Messiah’s great “amen”. The conductor at that point can pause, create a “caesura” before allowing the chorus and orchestra to proceed to the grand conclusion. The suspense, of course, is part of the drama of the performance!

This notion of the pause, the moment of silence, the gap, is found also, in eastern thought and architecture. I would like to quote a haiku from Basho ( 1644-94) a poet:

Old pond

Frog jumping,

Splash.12

What is Basho saying here (or not saying)? I suggest it is all about the differentiation between sound, and silence, continuo vs. change. In many Japanese gardens there exists a device that can produce the similar “splash” sound. It is called shishi odoshi or deer scare.13 Its purpose was to scare away the deer, intent on eating the leaves from the garden. Consisting of a bamboo pole, over a water source, it filled and thence dipped, unloading the water. Thence, returning to it’s original place it hit a stone, thereby creating a thumping sound. This interruption of the silence in the garden becomes, for me, the notion of time and the space between. In other words, it is the caesura… the gap between sounds. It also evokes the concept of Ma. A Japanese word, Ma roughly translates as “gap”,”space”, “pause” or “the space between two structural parts.” It is not something created by compositional elements, but rather in the imagination of the human who experiences these elements.14

Consequently, in architectural space, the gardens, particularly at Shisen-do and Ryoan-ji express

Ma as that “space between two parts.” At Shisen-do, one arrives and enters the villa, built originally by a Japanese warrior who decided, after so many battles, to retire, and write poetry. What is intriguing about this place is the relationship between the garden and the villa.

Pictured: Shisen-do engawa

One enters and sits on the “engawa”… a porch that is situated at the end of the villa and over looking the garden. The roof extends over the engawa, exactly ending at the edge of the sitting area. Hence it creates a spatial “room” that exists between the villa and the garden. In urban areas, with very limited space, it also serves as a gallery or “tsuboniwa” for the enjoyment of both the inhabitants as well as their guests.[10] But, at another level of experience, it is far more. It serves as a place of “liminality.” Mircea Eliade discusses the liminal in the notion of the threshold as the moment of betweeness, departing from the secular, and entering into the sacred[11] as for example, entering a cathedral. Consequently, it is in this context, also the pause, the gap, and hence, an expression of caesura.

What are these spaces really all about, in particular the concept of caesura and its relationship to continuo? Walter Benjamin 17observed that caesura does not lead to a complete separation of what is divided; as an instance of critical power a caesura only prevents the parts and levels in question from becoming mixed. A caesura keeps them simultaneously together… yet separate. Ma continues.

Change

There remains however, the reconciliation between continuo, caesura and change, if such is even possible. I’m reminded of an experience I had observing the summer home of Alvar Aalto called Muuratsalo, located on one of those lovely lakes of central Finland. It was at the time of its making, really a series of experiments in materiality, through Aalto’s extensive explorations with materials and how they respond to Nature’s forces. The latter aspect was what intrigued me. Such changes engage in the elements of architecture through time. In contrast to the seemingly

“timeless” iterations of Mies, locked into an ever present “now” and even Le Corbusier’s work, Aalto was confronting the mortality of architecture, recognizing that continuo engages change as well. However, his work was also about the discontinuous… the pause in the making. [12]i At Muuratsalo we observe walls that are seemingly incomplete, open to the forces of Nature… and ultimately expressive of the passage of time, and the emerging notion of the ruin.

Pictured: Muuratsalo Experimental House

Therefore, what is the ruin? What are its tasks? Juhanni Pallasmaa observed that “ the sole task of a ruin is to accompany time without resistance: vulnerability meets endurance.”[13] In their book “On Weathering” Mostafavi and Leatherbarrow [14]observed the notion of time through erosion as an act of subtraction as well as addition: older surfaces erode, but newer surfaces emerge. There is the notion of both continuo as well as change… a metamorphosis. To this extent then, the seemingly permanent edifice succumbs to the transience of time and nature’s forces. Consequently, I would argue that continuo and its caesura form an alliance with change reflected through their mutual acknowledgement of time as both movement and stillness that continues to symbiotically unite them.

Old pond

Frog jumping, Splash.

Illustration Sources

Orson Welles in “Citizen Kane”

RKO Pictures

Taliesin East

Mark Hertzberg

Shisen-do Temple, Kyoto

Robert Hermanson

Muuratsalo Experimental House

Flickr

[1] accessed 29, December, 2018,

[2] accessed 29, December, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continuity_editing

[3] Roger Ebert, “Citizen Kane,” The Great Movies, (Broadway Books, New York, New York, 2002), 112.

[4] Charles Jencks, Le Corbusier and the Tragic View of Architecture, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard UP, 1973).

[5] The Villa Schwob designed by Le Corbusier in 1916, located in La Chaux-De-Fonds, Switzerland was one example of the “elimination” of the surrounding site as part of his visual presentation of the building, accessed 29, December, 2018, https://en.wikiarquitectura.com/building/villa-schwob/

[6] “Shining Brow” was the Welsh name for Taliesin, given by Wright to his home at Spring Green, Wisconsin.

The narrative expresses his concern for maintaining the hill, by not building on top of it, but rather on its

“brow,” accessed 29, December, 2018, https://franklloydwright.org/site/taliesin-hillside/ Also, refer to Ken Burns film: Frank Lloyd Wright.

[7] Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, Frank Lloyd Wright, Florentine Films and WETA, Public Broadcasting Service, Arlington, VA, 1998.

[8] The conditions of opposites enunciates Heraclitus’ addressing the issue of change vs. continuity through what he called Logos. A moving object representing change, nevertheless, the underlying law remains the same…. Constancy, accessed 29, December, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unity_of_opposites

9 Soraj Hongladarom, “Metaphysics of Change and Continuity: Exactly what is changing and what gets continued?” Kilikya Felsefe Dergisi/Cilicia Journal of Philosophy, Mersin University, Turkey, Issue 2, 2015, accessed 29, December, 2018, http://philosophy.mersin.edu.tr/2148-7898/15-2/15-2-041.pdf

10 David Sax, “End the Innovation Obsession,” New York Times, December 7, 2018, accessed 29, December, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/07/opinion/sunday/end-the-innovation-obsession.html

11 accessed 12, April, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesura

12 accessed 12, April, 2019, https://kyotojournal.org/gardens/the -soundsilence-of-water/

13 accessed 12,April, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shishi-odoshi

14 accessed 11, April, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ma_(negative_space)

15 “The Many Face of Engawa”, accessed 22, April, 2019, http://www.interactiongreen.com/engawa-gallery/

16 Robert Hermanson, “Displacement: Exile or Tourism?,” ACSF Symposium X, Coral Gables, FL, 2018

17 Walter Benjamin, Critical Evaluations in Cultural History, Ed. Peter Osborne, (Routledge, London, 2005), 21.

18 Antony Radford and Tarkko Oksala, ”Alvar Aalto and the Expression of Discontinuity,” The Journal of Architecture 12:3, 257-280.

19 Juhani Pallasmaa, Encounters: Architectural Essays, Helsinki Rakennustieto Oy, 2005

20 Mohsen Mostafavi and David Leatherbarrow, On Weathering, (MIT, Cambridge, MA., 1993) 60.