Julio Bermudez

The Catholic University of America, Washington DC

bermudez@cua.edu

http://faculty.cua.edu/bermudez/

Sandra Navarrete

Universidad de Mendoza, Argentina docnavarrete@gmail.com

Introduction

Breathing and drinking are the most fundamental and personal interactions we have with our environment in terms of survival —interactions that are essentially experiential, embodied, and direct. Their importance lies in no small measure by the fact that we cannot live past 3 minutes without air and about 3 days without water. In contrast, we can survive around 3 weeks without food. In other words, our lives depend on our continued, repetitive, and usually unconscious intake of air and water.

Such existential dependence on breathing and drinking has not gone unnoticed. Since antiquity, most religions and cultures have allocated great significance to them and developed rituals associated with bringing attention to them in a variety of ways. Meditation, for example, often starts with consciously following one’s breath — a practice instituted at least 5,000 years ago in the Indian subcontinent (if not earlier elsewhere). Similarly, festivals often centering in alcoholic beverages have been important ways for communities to come together, celebrate, and address the challenges of social and personal existence since the beginning of history.

This paper considers the sacred and cultural dimensions of drinking. Particularly, we focus in one

“elixir” that has accompanied humanity since Neolithic times, about 8,000 years ago: wine.[1] Given the influence of alcohol in our mind, emotions and body and its association with the discussed survival drive to ingest liquids, it is hardly surprising that wine has occupied a relevant position in many spiritual traditions. We only need to consider Dionysus and his rites in ancient Greece and Rome, Judaism’s Kiddush and the Christian Eucharist among others. Another essential component of wine is its cultural and social origin and dependency. Quite simply, the know-how, production, distribution and consumption of wine demand some level of communal partnership. Furthermore, since wine comes from particular grapes cultivated on a particular land under particular sunlight and climate, it is rooted on a culture’s intimate relation to nature. Hence, different wine types around the world but also within a country and even a region are unique expressions of the unique culture and nature that give them origin.

The Bodega Salentein

Having established the essential links between wine, culture, nature and spirituality, let us now move into a remarkable contemporary example where their communion is celebrated in and through architecture. This is the Salentein winery, of Dutch industrialist Mijndert Pon, designed by the architecture office of Bórmida-Yanzón,[2] and located in the Valley of Uco, Province of Mendoza, in Western Argentina.

Mendoza is one of the 7 most prolific wine-producing regions in the world with a tradition dating back to colonial times (late 1500s). As a result, there is a long and proud tradition of Cuyo people (as they call themselves) in wine making that lives to this day. Over the last decades, many Mendoza wineries have become huge productions hubs that export vast quantities of wine to all corners of the world. Their great success has caused many of these wine companies to become more aware and interested in celebrating and representing the culture of wine to themselves and to the world (in no small measure, for marketing reasons). The positive result, however, has been the appearance of excellent wine architecture in every valley producing the beverage. The quality of these architectural efforts is remarkable not only in the number of good edifices built thus far but also in terms of the design and cultural experimentation allowed.

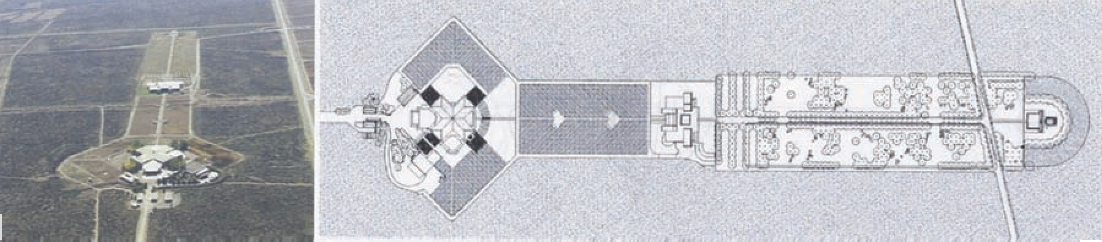

Figure 1: Aerial View and site plan of the Bodega Salentein complex (image credit: Bórmida-Yanzón office)

No better example of this trend is Bodega Salentein[3] because it not only addresses the cultural, natural, and productive dimensions of Cuyo wine country but also engages the phenomenological and spiritual territory of the wine experience. Project architect Eliana Bórmida is quite forthcoming on such intention. She is quick to affirm that the design of the Salentein complex follows compositional, siting, semiotic, and phenomenological intentions associated with sacred spaces across Western and non-Western history. The overall scheme is organized along a monumental, 1+ km axis (Fig.1, aerial view) that connects the actual winery (1999, left side of the plan in Fig.1) with the Chapel of Gratitude (2004, right end of the plan in Fig.1), having the Killka (2006, the formal entrance that includes a visitor center, museum, art gallery, auditorium and restaurant) in the center. A series of landscape architectural moves allows areas of wild and domesticated (vineyards) nature to work in unison with the general parti. The Northeast-Southwest monumental axis establishes not only a clear compositional and siting order but also a processional system that has the huge Andes mountains (and winery) at the end of the path. While symmetry is the fundamental design device, its presence is softened by the internal organization of the spaces and a landscape that resists human control.

Phenomenology

When architecture moves us, when it leaves a mark in our spirit, we know that we have crossed the invisible line toward the transcendent. This is the case of Bodega Salentein, that offers visitors architectural features that while starting in the body and materiality manage to turn space and time into existential occasions of great emotional, mental, and spiritual impact. We visited this bodega last December and this is our initial report that will be developed in full for our presentation in ACS 6.

According to Alvarez and Jurgenson,[4] phenomenology is defined by its focus on personal experience instead of facts based on social or interactional perspectives. More specifically, phenomenology “rests in four key concepts: temporality (lived time), spatiality (lived space), embodiment (lived body), and relationship or communality (lived human relation).” Our presentation will discuss how the Bodega Salentein rises one’s experience to the highest level in each one of these four categories, while addressing and aligning itself with the ancient tradition of connecting the experience of wine with culture, nature and spirituality, in this case via architecture.

Figure 2: The context (image credit: paper authors)

Approaching the Bodega Salentein prepares the visitor in a peculiar way (Fig.2). As we drive through the countryside to arrive to the winery, the immense scale of the Andes (with peaks over 20,000ft) makes its presence unavoidably and strongly felt as a formidable wall with gray-brown tones that often turn bluish. The Andes are the background setting against which the green and aromatic vineyards are appreciated.

Figure 3: The Killka (image credits: paper authors –left, and Bórmida-Yanzón – right)

We enter the Salentein complex, along a grand ceremonial axis, that not only ascertains a clear narrative order but makes us anticipates an architecture that won’t be forgotten. A great portal materialized as a simple prism, the Killka (which means ‘entry’ in the local Indian language), receives us (Fig.3). This building stops our path while framing the perspective toward the winery at the other end, with the towering Andes further behind. In this place, exquisitely resolved using water, light, stone, art, and sky through a minimalist architectural palette, our spirit finds home: Time is stopped, space felt, embodiment celebrated, and our humanity fortified.

Figure 4: The Winery. Left, the underground ‘temple’ to the wine. Right: wine-tasting area (image credits: left is Bórmida-Yanzón office’s, right is paper authors’)

From there, we move to the winery proper. We walk through vineyards that clocked our path. Upon entering the winery, we encounter the top opening of a central space that invites us to observe the underground… ! It is a total surprise. The excavation, surrounded by wine barrels, has a windrose at its center so as to not allow us to lose our bearings in this sea of sensations. Upon descending, this central space appears organized with tall supporting columns that both hold the deck above and define a magnificent lightwell (Fig.4, left). There is a strong contrast between the illuminated center and the cave-like, humid and dark space in the periphery. The contrast creates a mysterious and startling effect. Silence and echo, light and dark, materiality and scale, smell and dampness, coolness and texture, height and composition make us feel that we have arrived to an unique temple: the place where the womb of earth, the hands of Cuyo people, and some divine providence come together to deliver the sacred elixir. Its potent axismundi is strongly felt and crossing the other, monumental, horizontal axis. The wine barrels aligned around us are certainly sensed as participants in this sacred experience, in this sort of ritual that is taking place. Once again, time is arrested, space materialized, embodiment rejoiced yet elevated, and a fundamental relationship with it-all established. The result is a gift of transcendence. Within the winery, the areas destined to wine tasting are almost altars where the noble beverage coming out of this great land and culture is honored, celebrated, and partaken (Fig. 4, right).

Figure 5: The Chapel of Gratitude. Left, exterior, walking toward it. Right: interior (image credits: BórmidaYanzón office)

Moving now from the Killka toward the other direction (northeast), we walk again along the long axis, over half a kilometer in order to arrive to the Chapel of Gratitude. It is a hot, dry, and tiring but also exciting and empowering pilgrimage. As we move toward the Chapel, at pedestrian speed, we assimilate the scale of the land as we are wondering what we would encounter inside the Chapel. This was the sacred space through which Mr. Pon, the owner of Salentein, wishes to give thank to the land and community of Cuyo for all he had received from them. What could he have done to attain it? For sure, the murals framing the entry (that closed the long axis of the complex), the thick walls of rammed earth, and the simple yet perfect proportion of the building produce the right state of mind to cross the edge separating exteriority and interiority (Fig.5, left). Once inside, the magic of architecture does its job. The austere and wonderfully articulated interior, perfectly fitted to human scale makes our innermost being vibrate time and time again. The soft, almost ‘James-Turellesque’ light (that floods through a simplified cross), the rough floor, and the all pervading silence make us immediately gain a sense of profound gratefulness (Fig.5, right). Our heightened aesthetic experience is shared with other visitors: a timeless moment of numinous space where our body is in community and our hearts and minds find the numinous. We feel the land, the people, and the spirit. We can only pray in awe for the grace. How many wineries in the world have a chapel to give thanks? How could one not be moved ?

In short, the Salentein winery complex is charged with material dimensions, clear concepts, strong design composition, phenomenological narrative, and kind sensibility to produce an extraordinary experience. Its architecture of wine not only expresses Mendoza, Argentina, and our world today but it does so well that makes us appreciate the nuanced connections between land, culture and spirituality.

[1] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_wine (accessed 2014-1-21). Also, McGovern, Patrick. Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 2003).

[2] For more information about the office of Bórmida-Yanzón go to http://www.bormidayanzon.com.ar/ (accessed 2014-1-21)

[3] See http://www.bormidayanzon.com.ar/salentein/killka/; http://www.bormidayanzon.com.ar/salentein/bodega-salentein/ ; and http://www.bormidayanzon.com.ar/salentein/capilla-de-la-gratitud/ . See also http://www.bodegasalentein.com/en/bodega/galeria.html (all accessed on 2014-1-21)

[4] Alvarez, Juan L; Jurgenson, Gayou. Como hacer Investigación Cualitativa. Fundamentos y Metodología.

(México: Paidos Educador, 2003), pág 85 (translation is ours)