Michael J. Crosbie

University of Hartford, West Hartford, CT

crosbie@hartford.edu

Suzanne Elizabeth Bott

University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

suzannebott@arizona.edu

Introduction

The deserts of the world, and in particular, the American Southwest, while some of the most wondrous lands to behold for characteristics specific to these landscapes—color, light, flora, and fauna–also present a hostile environment that necessarily calls for what we describe as an “architecture of refuge.” Such places of refuge are an expression of deference to a desert land’s monumentality, its mountain backdrops, patterns of rivers, washes and arroyos, limited vegetation, and character-defining features that are the result of millions of years of aridity. Rising above all, the enormous, sun-drenched sky is the overarching reason for this need of a “protected refuge,” resulting in dramatic expressions of continuity between and among inhabitants.

This architecture of refuge is often beautifully and creatively expressed in built forms that recognize the desert’s vivid sense of place: one that entreats the visitor to dwell within a sheltered or otherwise protected setting, and search for beauty and meaning in a hostile and unwelcoming environment. As in the case at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West, one finds a cool and comfortable refuge from the heat of late spring and relief from the glaring light of the midday sun. We’ve found a campus of structures designed and built with sturdy materials from the earth in deep and brilliant colors that reflect the soil and stones when the light hits the hillsides just so, and which seem to settle into the land rather than imposing dominance over it. Taliesin West offers these designs in ways that demonstrate brilliant respect for the desert landscape, an awareness of its particular constraints and opportunities, and a desire to meet the needs of those who dwell in these lands with both protection and delight.

Desolate Space Versus Dwelling Place

The desert’s reputation as inhospitable is legendary. In Biblical scripture, the desert is often referred to as a “wilderness,” hostile to human habitation, dangerous for the traveler, and hardly the land of milk and honey. One of the most compelling examples is an Old Testament passage in the Book of Jeremiah, in which the “barren wilderness” is described as a “land of deserts and of pits…a land of drought and of deep darkness…a land that no one crossed…and where no man dwelt” (Jeremiah: 2:6). Some Islamic scholars note that in the Qur’an, the desert is a corollary to hell; for those who fail to obey, “the reckoning will be hard, and hell will be their abode: How wretched is its wide expanse!” (Ali, A., 1988, p. 13:18b).

Yet, desert lands have long been recognized as places perfectly suited for encountering the spiritual, thus giving them a deep sense of duality—danger and the divine—which we explore later in the paper. This duality is captured by geographer, Yi-Fu Tuan, who describes our meditation on such an open space, a space which has “no trodden paths,” as a refuge: “In the solitude of a sheltered place the vastness of space beyond acquires a haunting presence,” one that might summon us into contemplation (Tuan, Y., 1977, p. 54).

Norwegian architect and phenomenologist, Christian Norberg-Schulz, notes:

“Man dwells when he can orientate himself within and identify himself with an environment, or, in short, when he experiences the environment as meaningful. Dwelling therefore implies something more than ‘shelter,’ it implies that the spaces where life occurs are ‘places,’ in the true sense of the word. A place is a space which has distinct character. Since ancient times the genius loci, or ‘spirit of place,’ has been recognized as the concrete reality man has to face and come to terms with in his daily life. Architecture means to visualize the genius loci, and the task of the architect is to create meaningful places, whereby he helps men to dwell” (Norberg-Schulz, C., 1979, p. 8).

The result of these endeavors is the translation of nature into an ordered micro-cosmos or imago mundi, which separates and solidifies it, thus giving humans a foothold, whether precarious or firm, in the world (Eliade, 1957). This translation of nature into order leads to the condition of “dwelling,” in the existential sense of the word. As such, this opportunity to dwell facilitates the process of becoming, and the recognized phenomenon of being-in-the-world, as described by Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, where experiences are perceived and understood for their meaning.

‘Protected Refuge’: A Nuanced Definition

If the desert land is to be inhabited, one must acknowledge and defer to its immense and often merciless power through a “protected refuge.” Such a refuge allows the establishment of “place” in the midst of the desert’s immeasurable, uninhabited “space,” its haunting presence (in Tuan’s words). But it does something more. It allows connection to the spiritual to be encountered while offering necessary protection.

Here we need to make a note about terminology. Our position is that not all refuges are “protected.” Although synonyms for the word “refuge” include shelter, protection, safety, security, and asylum, other synonyms emphasize the spiritual dimension or function of a place of refuge. A refuge can be a sanctuary, a haven, a sanctum (think “inner sanctum”), a safe harbor, an ark, a retreat, or a hideaway. All of these synonyms for refuge do not necessarily imply physical protection–but they offer places for spiritual possibility.

The concept of refuge we wish to forward in this paper recognizes that a refuge can have a multidimensional quality: it can offer protection from the sun, rain, wind, dangerous animals and other predators. But certain refuges can also provide a place from which we can reflect upon and meditate on our place in the desert. These are the “protected refuges.” They provide protection from the physical danger of the desert, but by their very design, allow room for contemplation of a desert land’s duality: dangerous yet beautiful, threatening yet accepting, harsh yet yielding, intimidating yet inspiring.

Beyond the existential necessity of such a place as described by Tuan and Norberg-Schulz, contemporary researchers in Biophilic Design note this duality of refuge by recognizing its supportive, nurturing, and even homeopathic values. “Refuge” is one of the fourteen patterns of Biophilic Design identified by environmental designers at Terrapin Bright Green Design that can reduce stress, enhance creativity and clarity of thought, improve well-being, and enhance healing (Browning, W., et al., 2014, p. 3).

Such places of refuge offer protection through their siting and design. They feel safe because, in fact, they are–with sheltering roofs, overhangs, and protective backdrops. With these design features they provide a sense of retreat and withdrawal from looming dangers which enhances security as well as serenity. Such places, both natural and designed, that are separate and protected from their surroundings can foster contemplation and are embracing and protective without necessarily disengaging from the land (Browning, W., et al., 2014, p. 46). They are “of the place,” recognizing and acknowledging the inherent danger and providing boundaries and protection that support the possibilities of spiritual growth. Through design and siting strategies, such “protected refuges” establish continuity with the desert landscape, recognizing their inherent duality—physical and spiritual. They provide a place for existential dwelling and conscious beingin-the-world.

Ancient Protected Refuges

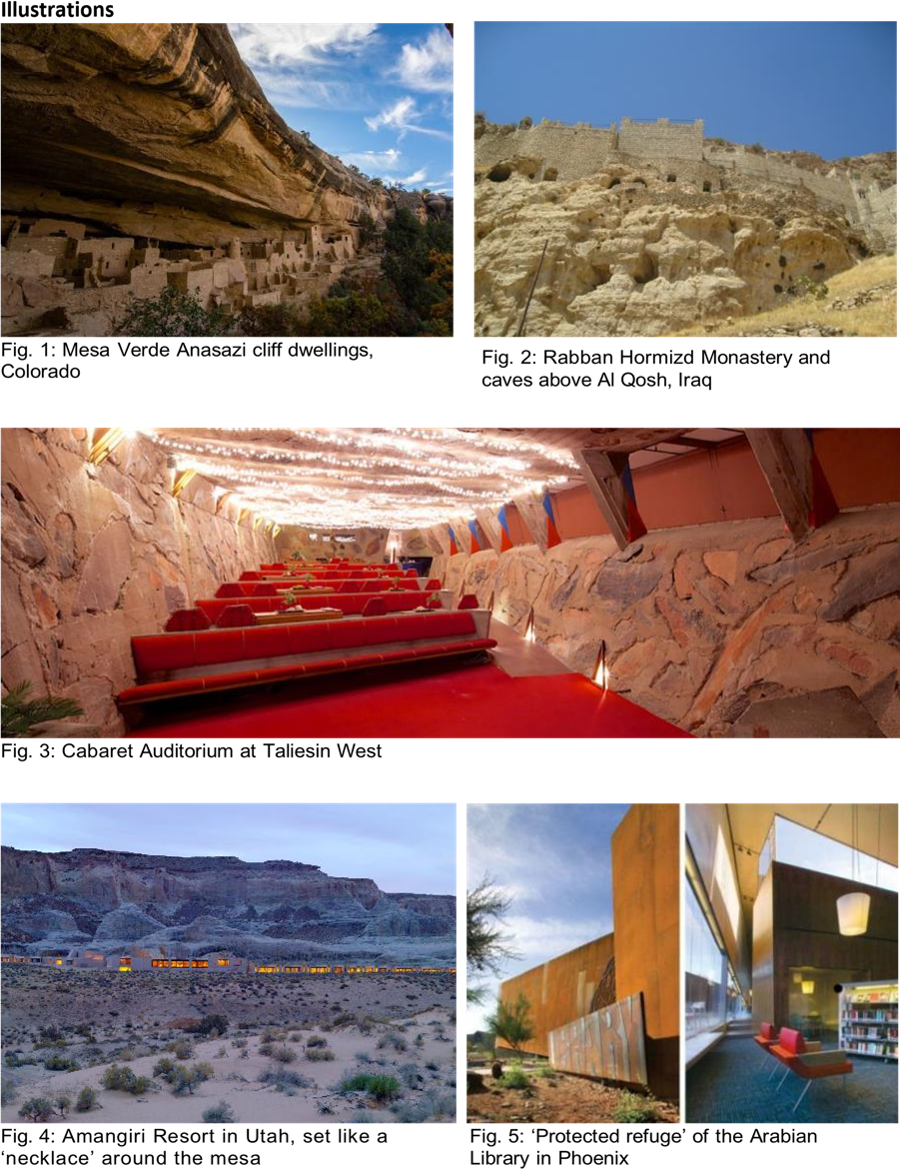

Early examples of such protected refuges are the cliff dwellings in the Four Corners regions of the continental United States, built by the Anasazi, the “Ancient Ones.” These indigenous people were ancestors of the modern Pueblo tribes, whose descendants include the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, Laguna, and Taos people. Part of the belief system of some of these tribes is that they were chosen and commanded by the Earth’s Caretaker, Maasaw, to go into the four directions of the Earth to find the “center” and establish home. After wandering the world, they arrived back in the region that is their ancestral land in northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico, where they were given a sign by Maasaw—the Great Light in the Sky—that this was the “center.” Their cliff-side and pueblo dwellings—and particularly the kiva form—epitomize the idea of the protected refuge, recognizing the power of the building set within the context of the desert terrain, to establish continuity with the landscape by connecting home, refuge, earth, and sky (Fig. 1). The kiva is traditionally a subterranean circular dwelling used for ceremonial and political purposes and social gathering. Access is provided by ladders through a hole in the ceiling, which not only provide protection and refuge from predators but offer symbolic rebirth (Lloyd, E. 2017).

In his book, The Wisdom of the Desert, Thomas Merton wrote of the third and fourth century hermits, mystics, ascetics, and cenobites who retreated to the deserts of Egypt, Palestine, Arabia, and Persia to turn their backs on civilization in their quest for salvation from society (Merton, T. 1960, p. 3). Monasteries eventually were founded and built in these desert places, but the first places of refuge for many of these hermit fathers were in desert mountain regions–literally in shelves hollowed into mountain walls.

E.A. Wallis Budge, who visited Rabban Hormizd Monastery in northern Iraq in 1890, described these protected refuges: “In the hills round about the church and buildings of the monastery are rows of caves hewn out of solid rock, in which the stern ascetics of former generations lived and died.” (Fig. 2) He goes on to comment that some of these caves “…have niches hewn in their sides or backs in which the monks probably slept, but many lack even these means of comfort. The cells are separate one from the other, and are approached by narrow terraces, but some are perched in almost inaccessible places….” (Budge, E., 1902).

Contemporary Protected Refuges

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona is a modern expression of a protected refuge. Its siting utilizes the McDowell Mountains to the northeast as a backdrop, while Wright’s buildings occupy an elevated plateau with a commanding view of the valley to the west. The materials of wood, stone, and glass reflect the native materials of the Tonto National Forest and the form and massing rest within the angle of repose of the mountains. Interior spaces span the breadth of shelter from deeply enclosed, cave-like spaces to exuberant solaria that embrace the omnipresent sun, moon, and stars (Fig. 3).

Opportunities for re-experiencing features of the natural landscape have been designed into the structures, where, for example, one can move from a constrained or compressed area similar to a slot canyon, through a passageway and upon turning a corner, suddenly emerge with a sense of release into an openness of space. There are other canyon-like areas where a linear path offers the only form of direction, which feels obvious and logical, and in so doing, is comforting. The introduction of water into the setting offers relief in the form of both physical and psychological cooling as well as the sensual pleasure from the seeing and hearing moving water within the arid landscape.

Similarly, the Amangiri Resort and Spa in Canyon Point, Utah, offers a contemporary iteration of these traditional design forms that has all the hallmarks of a protected refuge within its spectacular setting. Architect Rick Joy’s site design, like Wright’s at Taliesin West, embraces the site and takes the elegant, reflective form of a jeweled necklace placed gently around the neck of the mesa (Fig. 4). Thirty-four private rooms carefully arranged around the walls of the mesa look outward to the desert floor. Each room frames views of the mesa, the sky above, and the resources of greatest importance in the desert: the life-giving spring and the aquifer below. The provenance of water in the harshest of landscapes—as with wells, oases, and ephemeral streams–appears as divine intervention and great beneficence.

A third example, on the scale of a single building, is the Arabian Public Library in Scottsdale, which establishes a protected refuge against the heat island effects of the suburban sprawl of Phoenix. The plan design by Richard + Bauer Architects rotates clockwise much like a slot canyon, and folds over and within itself, creating a sheltered refuge at the center of the building for desert plants to thrive within a miniature courtyard. The courtyard is visible from within three sides of the library and provides a view of plants and sky to be enjoyed by library visitors (Fig. 5). The entry experience of the library offers one of compression and release, comparable to exiting a sheltering kiva into the sky city at Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico, or moving throughout the structures at Taliesin West.

Conclusion

The earliest desert inhabitants, from biblical wanderers to indigenous tribal groups throughout the world’s desert lands, created ingenious solutions for “protected refuge” to accommodate the danger and challenges of the stark landscape while embracing its surreal beauty and the possibilities of spiritual transformation. The designs reflect continuity with the desert as a place of duality, through time as well as space, human needs as well as spiritual. The organic development of line and form not only provides refuge, but also provides the inhabitants of desert lands a place from which to embrace and celebrate the vast space and connection to the cosmos that make the desert a place for encounters with the divine.

References

Ahmed, Ali. Al-Qur’an (translation). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Browning, William, Catherine Ryan and Joseph Clancy. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design. New York: Terrapin Bright Green, 2014.

Budge, E. A. Wallis, (ed.) The Histories of Rabban Hormizd the Persian and Rabban Bar-Idta. London: Luzac & Co., 1902. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabban_Hormizd_Monastery, accessed April 28, 2019

Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion, translated from French: W.R. Trask. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. 1957.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and time: A translation of Sein und Zeit. SUNY press, 1996.

Lloyd, Ellen. Hopi’s Encounter With Maasaw – The Skeleton Man And His Gift Of Sacred Knowledge.

http://www.ancientpages.com/2017/05/05/hopis-encounter-maasaw-skeleton-man-gift-sacredknowledge/, accessed April 28, 2019.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of perception. Routledge, 2013.

Merton, Thomas. The Wisdom of the Desert, New York: New Directions Books, 1960.

Norberg-Schulz, Christian. Genius loci: Towards a phenomenology of architecture. New York: Rizzoli International Publishers, 1979.

Yi-Fu Tuan. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977.

Illustrations

Figure 1: National Park Service

Figure 2: Suzanne E. Bott

Figure 3: Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Figure 4: Studio Rick Joy

Figure 5: Richard + Bauer Architects