Nader Ardalan

Ardalan Associates, Design Architects

nader.ardalan@gmail.com

Introduction

Rumi is the most respected and popular mystical love poet of Iranian Culture and in the 21st c. He has also become America’s most well-known metaphysical love poet.[3] But, who transformed this pious 13th century scholar into this transcendent mystical lover? It was his “soul friend,” [4] Shams of Tabriz who was indeed Rumi’s “Sun” that illuminated in him the evocative and deeply spiritual dimensions of transcendent love of the Divine.[5]

The spiritual riddle placed before me as an Architect was how do you design a meaningful Cenotaph in the 21st century for Shams, this medieval, culturally significant and highly controversial, mystical figure? When the Design Competition in Iran in 2012 failed to find a suitable solution for his mausoleum, I sitting in faraway America, thought it a great shame if this historic figure might not be architecturally memorialized properly in his birthplace of Iran. Therefore, I was genuinely motivated to personally donate on 12.12.12 to the Rumi & Shams Foundation a set of hand-drawn ink design drawings that I sensed might be more valid and worthy.[6]

Scope and Purpose

This brief essay explores a preliminary design response based upon my own inner dialogue with Rumi and Shams through a collective surge of the imagination process that I have termed Khaliq I Jadid -The New Creation.[7] It includes six years of discussions with locals in Khoy and the cultural adepts of Iranian culture to glimpse an understanding of the core World Views of Rumi and Shams of the Transcendent Unity of Existence (Wahdat I Wujud [8]) that is based upon a Manifest/Hidden (Zahir/Batin) concept of Reality found in the Quran. Rumi has written: “Form is a thing’s outward appearance, meaning its inward and unseen reality”[9]. Their message is “Shams was the mirror in which Rumi contemplated God’s Perfection” [10] and the profound transformative impact of Shams on Rumi was summed up in three words: “I was raw, I was cooked, I was burned.” [11]

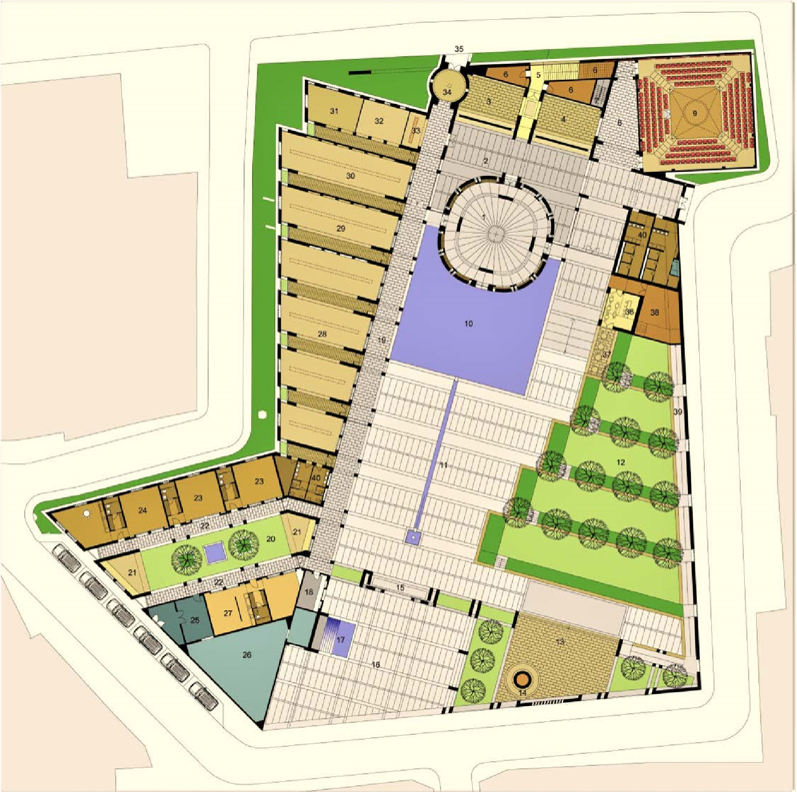

The memorial garden design of the Cenotaph of Shams is set within a large site situated in an urban residential neighborhood of the old city of Khoy, which enjoys a moderate climate in northwest Iran. A small section of the site has historically served as a cemetery where a symbolic tombstone of Shams presently lies, marked by an existing 14th c. Seljuk brick minaret that will be preserved. In close urban proximity lies the revered Buhloul Shrine to the south and a living ritual pilgrimage path that connects the two sites. Due to the very traditional Islamic cultural context, the proposed design recognizes the direction for daily prayer toward Mecca of the site that is 15.89 degrees from south toward the SW. This consideration inspired the rotation of the total project orientation towards Mecca, thus providing a subliminal and conscious awareness of the spiritual sense to pervade the entire design.

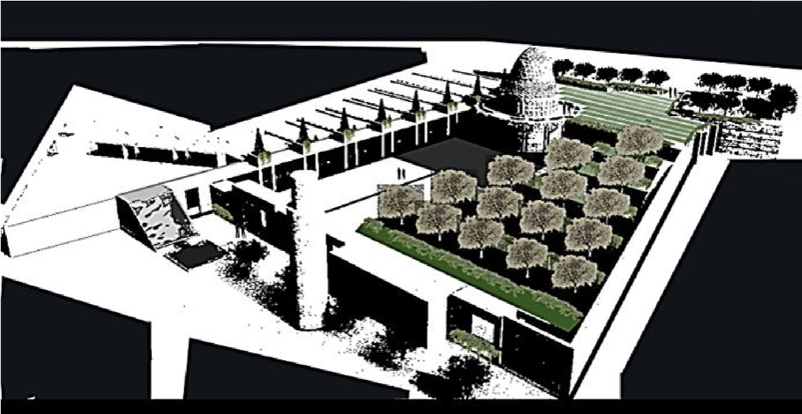

The archetypal paradise garden offers places of repose, quiet introspection and rooftop extrospection of distant mountains and the celestial heavens; of landscaped terraces of fragrant flower beds, cooling shade under groves of crape myrtle trees, known for their colorful and longlasting flowers which occur in summer; of columns of tall cypress trees naturally irrigated by water channels with their soothing sounds of water flowing gently into a mirror pool and the lyrical sounds of poetry being recited in a tea room.

“Twas a fair orchard, full of trees and fruit

And vines and greenery. A Sufi there

Sat with eyes closed, his head upon his knee,

Sunk deep in meditation mystical.

“Why”, asked another, “dost thou not behold These

Signs of God the Merciful displayed

Around thee, which He bids us contemplate?”

“The signs,” he answered, “I behold within;

Without is naught but symbols of the Signs.” – Rumi

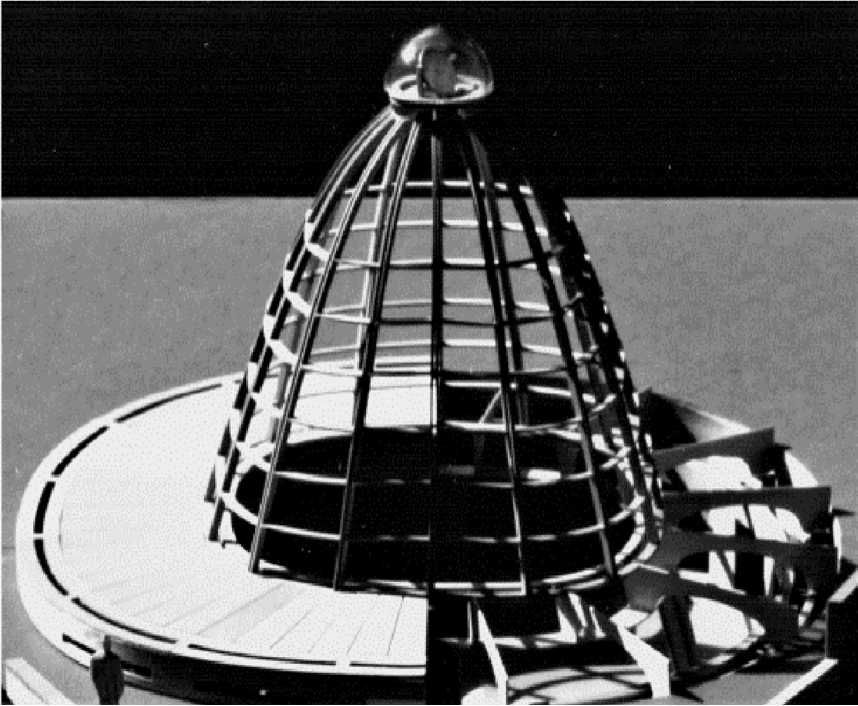

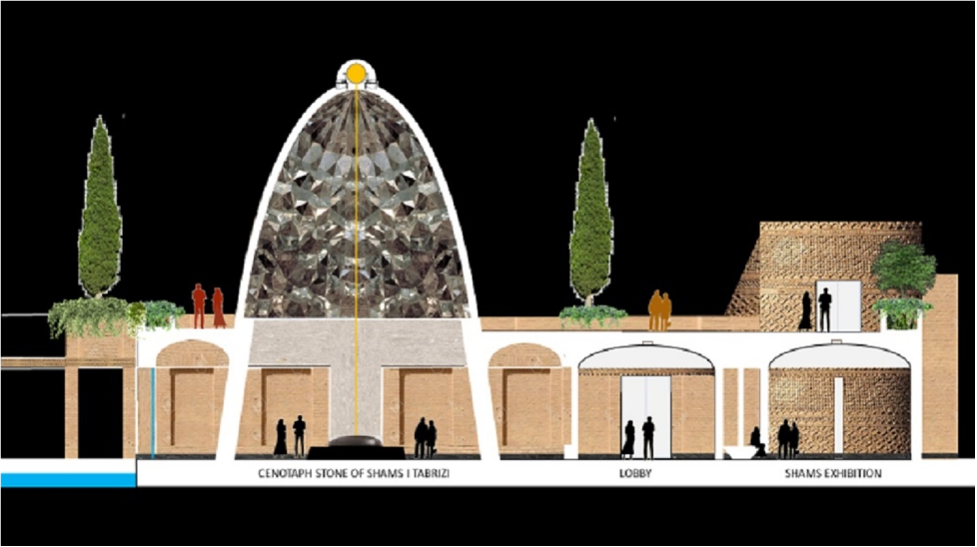

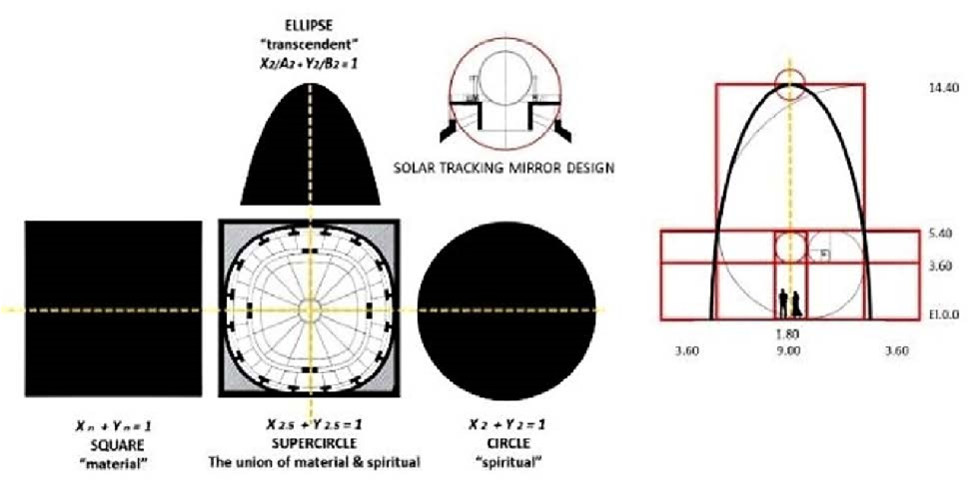

Rising out and above an embracing roofscape of undulating brick vaults, the vertical form of the Cenotaph holds the pivot of the entire space. Conceived as a symbolic super-circle ellipsoid clad in patterned buff brick, its apex holds a solar tracking mirror that beams a ray of sunlight down upon the memorial tombstone of Shams in the sanctuary space below. Surrounding the main sanctuary are exhibition rooms displaying the Sufi poetry of Shams and Rumi, a lecture hall, research library with study spaces, visiting scholar accommodations, administration and support facilities.

The design is driven by considerations for human scale and golden mean proportions of spaces with a simplicity of means to innovatively re-invigorate the use of traditional crafts and local materials of buff brick walls, ‘Gahgel’ [12] plaster and ’Ayeneh Kari’[13]. Utilizing climatic adaptation measures to achieve a sustainable, efficient and healthy heating and cooling system that would allow maximum natural ventilation, the result is a low-energy use building. Designed to interact with the seasons and the exterior environment in a more natural way, a ground-source heat pump channels naturally heated or cooled water into the buildings, where it runs through radiant floor slabs to help regulate temperature and provide human comfort for seating or performing a prayer directly on the honed, black basalt paving, locally sourced.

The site has already been nominated to be the UNESCO World Heritage List. Thus, the memorial garden and the building spaces will be open to all visitors of different faiths, nationalities and walks of life enhanced by the pervading project design theme of “Transcendent Love”, emphasizing qualities of compassion, intimacy, piety and the ineffable. It seeks to evoke the words of Alberto Perez-Gomez: “it responds to a desire for an eloquent place to dwell, one that lovingly provides a sense of order resonant with our dreams, a gift contributing to our selfunderstanding as humans inhabiting a mortal world”[14]

Conclusion

The apparent dichotomy between meaning and form is the mainstay of Rumi’s teaching and they are inextricably connected. The design seeks to show how form continuously derives from meaning and meaning manifests itself as form. Since the two are outward and inward aspects of a single reality. Hence, the design emphasizes a concept of growth, continuity and interrelatedness – Rumi and Shams, sharing in the alchemy of the revelation of each other’s inner, hidden gold through deeply spiritual dimensions of friendship and platonic love.

Figure 1.Preliminary Site Ground Floor Plan

Figure 2. Aerial Perspective View from the South of the Project

Figure 3. Study Model of the Super-Circle Ellipsoid

Figure 4. Preliminary Design of West Elevation

Figure 5. Preliminary Section though Main Sanctuary Space, Arrival Lobby and Exhibition Hall

Figure 6. Evolution of the Super-Circle Ellipsoid & Golden Mean Setting Out of Sanctuary Dome

[1] Ishq is the Persian/Arabic word meaning “love”- the core concept of the connection of man and the Divine in Islamic Mysticism

[2] Shams literary means: “Sun”

[3] Coleman Barks, Rumi: Soul Fury, Rumi & Shams Tabriz on Friendship, Harper One, 2014

[4] Ibid

[5] Elif Shafak, Forty Rules of Love, Viking, 2010

[6] Through a young gifted colleague, Sam Tehranchi Director of Design Core Consultants of Toronto & Tehran, who agreed to be the Executive Architect, a professional services contract was signed in 2018 by his firm with the Ministry of Culture, Miras I Farhangi. This process allowed me to comply with US law & provide Pro Bono Design services.

[7] For explanation of Khalq I Jadid design process, refer to my chapter in Reza Shirazi, Contemporary Architecture and Urbanism in Iran, Springer,2018.

[8] Toshihiko Izutsu, Sufism and Taoism: A Comparative Study of Key Philosophical Concepts, University of California Press, 1984

[9] William Chittick, Me & Rumi, The Autobiography of Shams-I Tabrizi, Fons Vitae, 2004

[10] Ibid

[11] Jalal al-Din Rumi, Jawid Mojaddedi (translator), The Masnavi, Oxford University Press, 2008

[12] Persian name for refined Adobe or mud/straw plaster

[13] Contemporary and new interpretation of traditional Persian art of cutting mirrors into small pieces placed in geometric shapes over plaster.

[14] Perez-Gomez, Alberto. Built upon Love: Architectural Longing after Ethics and Aesthetics. Cambridge, London: The MIT Press, 2006, p.3.