Phoebe Crisman

University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA

crisman@virginia.edu

Wakȟáŋyeža kiŋ lená épi čha táku waštéšte iwíčhuŋkičiyukčaŋpi kte.

Let us put our minds together and see what life we can make for our children.

– Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake (Chief Sitting Bull)1

There is a profound overlap between Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural conception of continuity and the world view and traditional architecture of many Native American tribes. Like the pueblo, earth lodge, and tipi typologies, Wright’s buildings seek to integrate with the land, climate, culture, and material of a place. The architecture of Taliesin West connects deeply with the physical and spiritual nature of the Sonoran Desert through site-sourced stone and low, planar forms that provide shade and channel air. Wright described living in the desert as a spiritual cathartic and how “Our new desert camp belongs to the Arizona desert as though it had stood there during creation.”2 Pueblo architecture and earth lodges of the Great Plains attained this situatedness. Yet, traditional Native American spirituality goes beyond site specificity to understands everything as related—stones, plants, creatures—all part of a living universe. While a compelling vision, Sioux scholar Vine Deloria Jr. rejected the possibility of American Indians living in harmony with nature today because indigenous culture has been radically transformed over time and deliberately destroyed by US government policies.3 Amidst this loss, however, Deloria found American Indian spiritual traditions still more in tune with the needs of the modern world than Christianity with its historic support of imperialism and disregard for ecology.4 What does the culture of indigenous peoples mean for their architecture today? And architecture more broadly?

These questions were explored through the collaborative design of a gathering place for the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate to reclaim their culture, spirituality, and tribal sovereignty.5 The Sisseton and Wahpeton are two bands of the Dakotah tribe and the larger Očhéthi Šakówiŋ. The word Dakotah may be translated as friend or ally and derives from the word WoDakotah, which means “harmony—a condition of being at peace with oneself and in harmony with one another and with nature.”6 Yet, over sixty percent of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate (SWO) live in poverty and forty percent are unemployed.7 Poor education, lack of skills and jobs, substance abuse, and youth suicide are barriers to individual and community thriving. Understanding current tribal conditions requires a knowledge of Dakotah history. Human rights atrocities during the Dakota war, the subsequent mass internment of over 1,700 women and children at Fort Snelling, and forced displacement from their wooded homelands in Minnesota to barren prairie reservations still affect the tribe. Settler colonization and mandatory assimilation were achieved through federal laws that prohibited speaking the Dakotah language and engaging in Native spiritual practices. Children were forcibly removed from families and sent to Christian boarding schools that eradicated their Dakotah identity, language, and way of life. Tribal trauma also includes the historic discrimination that accompanied European contact and continues today. Yet the Dakotah nations have survived and are in the process of defining for themselves how they will integrate their cultural knowledge, practices, and Dakotah language with their current affairs.8

Seeking to support those efforts, a transdisciplinary team of University of Virginia (UVA) faculty and students worked with SWO citizens to design a self-sufficient and sustainable cultural center on their Lake Traverse Reservation in South Dakota.9 The group explored how architecture can embody culture and spirituality through space, form, material, and use. Native American ecological paradigms10 and cultural identity were studied as ways of healing the effects of systemic social injustice and influencing the architecture—from form to materials and making. Also, the design process was informed by theories of agency11 and community engagement,12 feminist writings by Donna Haraway, Sandra Harding, and Caroline Ramazanoglu,13 and Richa Nagar’s work on co-authorship and storytelling as tools of empowerment.14 The negativity many Dakotah people feel toward “carpentered,” rectangular forms and spaces were explored during a four-day co-design workshop on the Reservation.15 By nurturing relationships with tribal members and recognizing different subjectivities of the participants, the UVA students and faculty were able to situate their design research within the context of knowledge production on the Reservation.

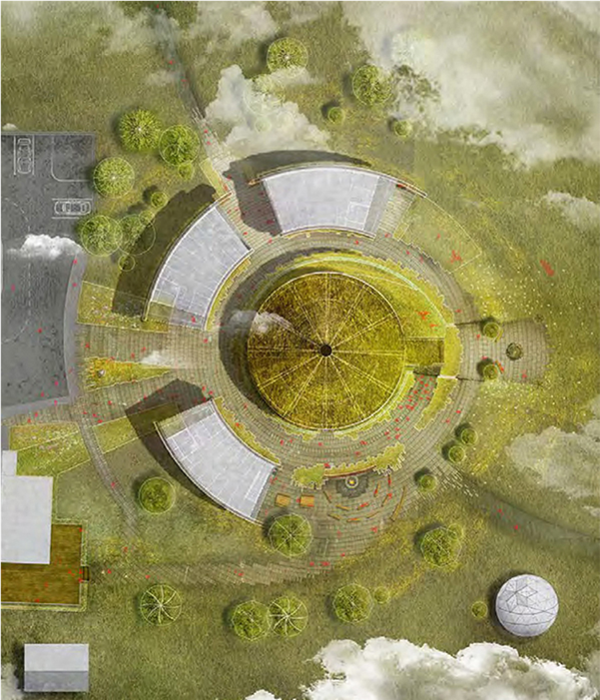

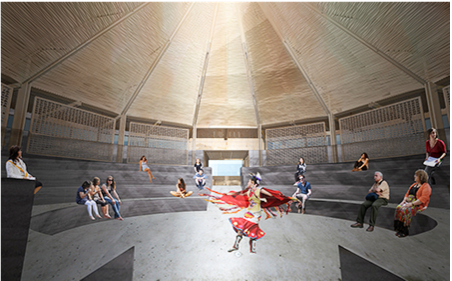

The Cultural Center will be located at the Sisseton Wahpeton Tribal College, where massive, nondescript rectangular buildings float on a field of asphalt within the larger Jeffersonian grid.16 Asserting autonomy from this cartesian condition, the design weaves into a restored tallgrass prairie at the campus edge. A village of small, off-the-grid studio buildings encircles a central tiotipi inspired by traditional earth lodges. The tiotipi will support storytelling, theater, music, and dance performances. Students of all ages will learn about traditional crafts and new film and digital media practices in the studios. Archive and gallery spaces will safely store and display historical tribal artifacts. Intertwined gardens and work courts will provide places to learn about native medicinal plants, seed saving, and Native foods. The holistic Dakotah world view directly influences the architecture. The ceremonial directions–east, west, north, south, sky, and earth— establish the everchanging center of their universe. Every place can be a ceremonial center, the here and now, representing all times taking place simultaneously, and making ‘whole again what has now become disassociated and chaotic’.17 Situated within this cosmological model, the cultural center will be a place to make the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate whole again. Akin to Dewey’s idea of continuity, the center, like an organism, “does not live in an environment; it lives by means of an environment.”18 Powered by wind and sun, the buildings will collect rainwater and be warmed by the earth’s geothermal heat.Made of locally sourced wood, rammed earth, and hemp insulation, the buildings are designed to be built in phases by tribal members, vocational students, and UVA students working together without heavy equipment. The construction process itself will build tribal capacity and community.

By creating a place for intergenerational education and reflection that resonates with Dakotah values, the architecture of the cultural center seeks a central role in the tribe’s effort to undo colonial legacies, advance economic and political sovereignty, and support cultural flourishing. This co-design project was not structured as a gift between benefactor and recipient, but rather as a process of exchange and mutual expansiveness between two diverse communities—each sharing their knowledge and ways of being in the world. Many lessons learned in the process might be transferred to non-indigenous communities in search of an architecture of meaning.

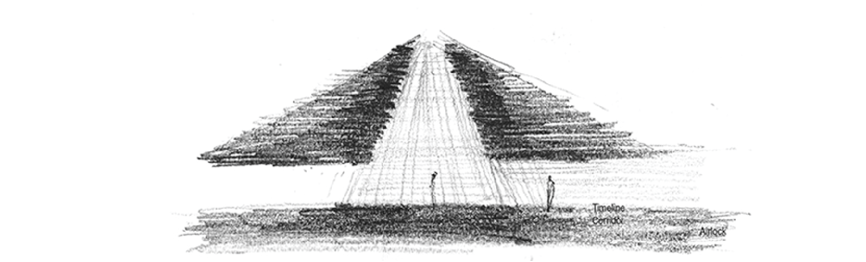

Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Cultural Center in restored prairie landscape

UVA team with Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate collaborators in earth lodge

Interior of tiotipi and surrounding gallery / Image credits: UVA Crisman SWO Collaborative Studio, Fall 2018

Notes

1 Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake, known as Chief Sitting Bull, was a Lakota leader credited with this quotation.

2 Quote credited to Frank Lloyd Wright on Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation website https://franklloydwright.org/frank-lloyd-wrights-taliesin-west/ [accessed 12 January 2019]

3 Vine Deloria Jr., Custer Died for your Sins: An Indian Manifesto (New York: MacMillan, 1969) and Vine Deloria Jr., Spirit and Reason (Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 1999).

4 Vine Deloria Jr., God is Red: A Native View of Religion (New York: Putnam, 1972).

5 Darren Ranco and Dean Suagee, “Tribal Sovereignty and the Problem of Difference in Environmental Regulation: Observations on “Measured Separatism” in Indian Country,” Antipode, 39/4 (2007), 691-707.

6 Suzanne J. Crawford and Dennis F. Kelley, American Indian Religious Traditions: An Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, Denver and Oxford, England: ABC Clio, 2005).

7 Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate website http://www.swo-nsn.gov [accessed 10 January 2019]

8 Jack D. Forbes. “Nature and Culture: Problematic Concepts for Native Americans,” in Indigenous Traditions and Ecology, ed. John A. Grim (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 119.

9 Collaborators included Dustina Gill, Director of the native NGO Nis’to; Erin Griffin, Director of Dakotah Studies at the Sisseton Wahpeton Tribal College; University of Virginia Professor of Architecture Phoebe Crisman and Professor of Global Development Studies David Edmunds; Adriana Greci-Green, Curator of Indigenous Arts of the Americas at the Fralin Museum of Art; and Karenne Woods, Director of Indian Programs at the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities.

10 See Cassandra Barnum, “A Single Penny, an Inch of Land, or an Ounce of Sovereignty,” Ecology Law Quarterly, 37 (2010). Also Darren Ranco and Dean Suagee, “Tribal Sovereignty and the Problem of Difference in Environmental Regulation: Observations on ‘Measured Separatism’ in Indian Country,” Antipode, 39/4 (2007), 691-707.

11 According to Anthony Giddens, [Agency] means being able to intervene in the world, or to refrain from such intervention, with the effect of influencing a specific process or state of affairs. See Anthony Giddens, The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 14. Also Bruno Latour, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987) and Tatjana Schneider and Jeremy Till, “Beyond Discourse: Notes on Spatial Agency,” Footprint: Delft School of Design Journal 4 (2009).

12 Ernest Boyer, “The Scholarship of Engagement,” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1996). Mark Wood, “From Service to Solidarity: Engaged Education and Democratic Globalization,” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 8, 2 (2003), 165-181.

13 Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies, 14, 3 (1988), 575-599. Sandra Harding, Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Thinking from Women’s Lives (New York: Cornell University Press, 1991). Caroline Ramazanoglu and Janet Holland, Feminist Methodology: Challenges and Choices (London: Sage, 2002).

14 Richa Nagar, Muddying the Waters: Coauthoring Feminisms across Scholarship and Activism (Urbana, Chicago and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2014).

15 Fixico, D. 2003. American Indian Circular Philosophy, The American Indian Mind in a Linear World. Routledge: 41-62.

16 William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill & Wang, 1983). Carolyn Merchant, Ecological Revolutions: Nature, Gender, and Science in New England (Chapel Hill: University of South Carolina Press, 1989).

17 Deloria, Spirit and Reason, 55.

18 John Dewey, Logic. The Theory of Inquiry (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1938), 25. Also Kevin Armitage, “The Continuity of Nature and Experience: John Dewey’s Pragmatic Environmentalism,” Capitalism Nature Socialism, 14, 3 (2003), 49-72.