Trent Smith

University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah htsmith@gmail.com

Summary Statement

Things are such, that someone lifting a cup, or watching the rain, petting a dog or singing, just singing – could be doing as much for this universe as anyone. Rumi

This paper explores a series of spiritual ritualistic experiments to sacred harp methodology of worship within the churches of Christ found in the Intermountain West region. It is primarily focused on youth and college groups and the heightened awareness of acoustics in worship and the resulting phenomenological experiences had in a variety of settings. These experiments took place over a single summer in 2012 in groups of 5, 15, 35, 70, and 120 worshippers of different ages, though primarily composed of adolescents between the ages of 13 and 20.

This paper was conceptualized three years ago, however it was not until the thematic quote of this seventh conference from Rumi[1] and the organizations’ solicitation of research that dealt with non-architectural space and the importance of ritual that I considered these experiments worthwhile to document and further cement in the context of spiritual research and writing. The experiments were born out of a great desire to enhance worship, teach historical singing through re-enactment, and above all try to create a series of moments that raised awareness and respect for what many youth considered trivial worship to their God. They were not academic in nature, however I believe that an incredible amount can be learned for young designers and worship leaders alike reaching for ways to engage their adolescent church goers.

Context of the Churches of Christ

Context into the current state of worship in the churches of Christ is critical to understanding why these experiments were so important to both study and to reflect on how the spirit of worship, particularly among adolescents, is being lost in the current state of technological bombardment and distraction in adolescent spiritual experience.

Many teens at this time period were struggling to embrace the rigorous and at times restrictive nature of worship with sacred-harp songs, being a-Capella in format and often with songs that were composed in the 1800’s that did not speak to the current state of adolescent relationships with God. The team of researchers at the Barna Group[2] spent much of the time between 2005 and 2010 exploring the lives of young people who drop out of church involvement. They produced a resulting set of findings from a nation-wide survey and analysis:

In general, there are three distinct patterns of loss: prodigals, nomads, and exiles.

One out of nine young people who grow up with a Christian background lose their faith in Christianity—a group described by the research team as prodigals. In essence, prodigals say they have lost their faith after being a Christian at some time in their past. More commonly, young Christians wander away from the institutional church—a pattern the researchers labeled nomads. Roughly four out of ten young Christians fall into this category. They still call themselves Christians but they are far less active in church than they were during high school. Nomads have become ‘lost’ to church participation. Another two out of ten young Christians were categorized as exiles, those who feel lost between the “church culture” and the society they feel called to influence. The sentiments of exiles include feeling that “I want to find a way to follow Jesus that connects with the world I live in,” “I want to be a Christian without separating myself from the world around me” and “I feel stuck between the comfortable faith of my parents and the life I believe God wants from me.”

Overall, about three out of ten young people who grow up with a Christian background stay faithful to church and to faith throughout their transitions from the teen years through

their twenties.

David Kinnaman, who directed the research, concluded: “The reality of the dropout problem is not about a huge exodus of young people from the Christian faith. In fact, it is about the various ways that young people become disconnected in their spiritual journey. Church leaders and parents cannot effectively help the next generation in their spiritual development without understanding these three primary patterns. The conclusion from the research is that most young people with a Christian background are dropping out of conventional church involvement, not losing their faith.“[3]

Many of the youth that I was working with at the time (as a youth and college minister) fell into the nomad and exile category. They were torn additionally by their specific denomination, church of Christ, who have embraced many of the traditions of Sacred Harp singing and morphed them into their own, unwaveringly a Capella worship in particular.[4]

The Churches of Christ are characteristically known for having small attendance, and although they are autonomous in church hierarchy, this small size is remarkably consistent throughout the country:

Although the Churches of Christ has almost 13,000 congregations in the United States, 45 percent of these have fewer than 50 members and more than 70 percent have fewer than 100 members.[5]

This unique size often leaves members feeling like they are only part of a few people who understand their spiritual focus, compounded by the fact that the Church of Christ distribution is not even throughout the states, but primarily focused in the Southeastern Region, known as the ‘Bible Belt’ since 1924 when coined by American journalist and social commentator H. L.

Mencken, in the Chicago Daily Tribune.[6]

Utah, for instance, in most recent years, has 8 churches of Christ in the state, only 2 in it’s capitol. Similar numbers exist in neighboring Intermountain West states Idaho and Colorado, where these experiments take place. Having such a unique style of worship, without the addition of instruments, and given only recent mention in the media[7] causes many adults and even more youth to be shy or very cautious about bringing friends for service, let alone encouraging involvement in worship. It also contributes to an enormous feeling of being alone, isolated, with the dominate religions in the West using instrumental worship only compounds the matter.

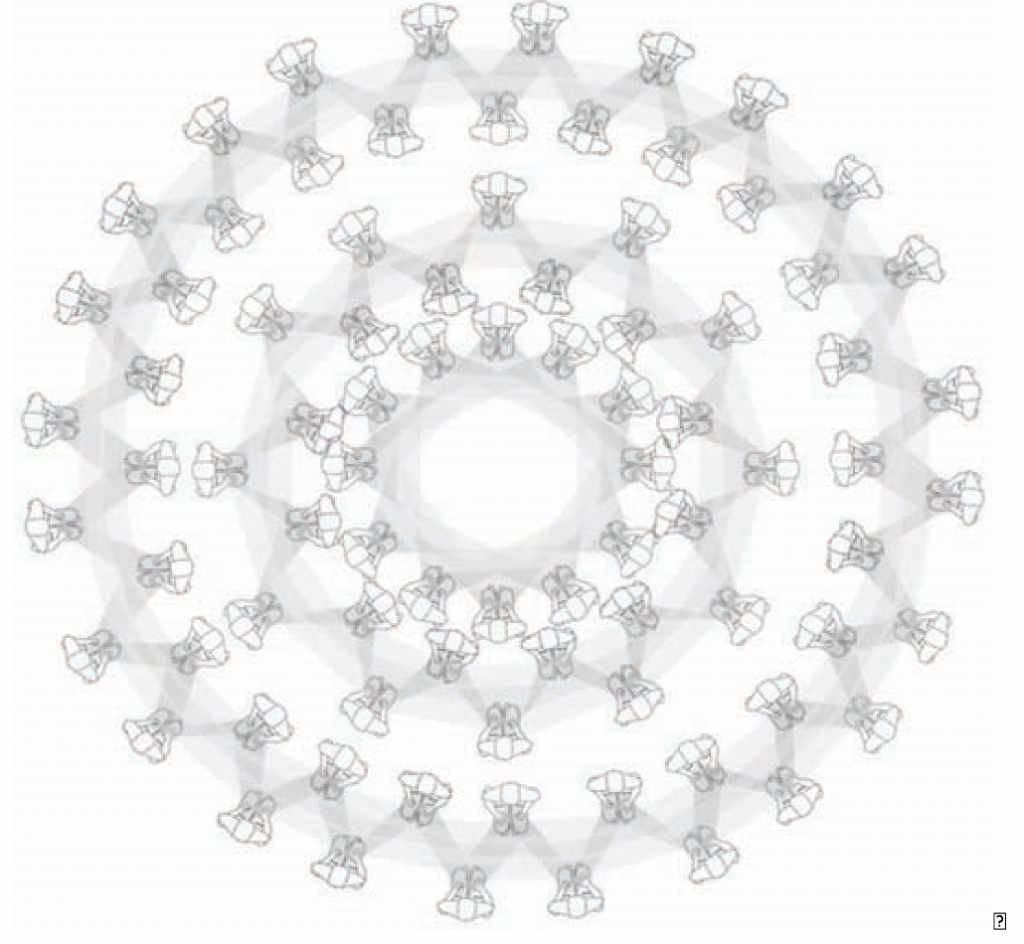

As such, the adolescents in these churches look forward to ‘church camps’, weeks during the summer months where a handful of youth from each church come together for worship, study, and games but also to stay connected with a very isolated group of believers who can share and be open about testimony and struggles they face in their own areas. These camps are attended by the neighboring states, but rarely reach attendance over 150 campers. This is contrasted in the Southeast, where thousands gather on a much more regular basis throughout all months to study, worship, and fellowship. Numbers can reach into the hundreds and even thousand mark with only visitors from neighboring cities, where there is easily an incredibly dense network and even less persecution that youth face due to the readily available support network.

In the Intermountain West in particular, rallies, retreats, and camps can only happen February through October, with both family-themed holidays as well as much more severe winter conditions serving as a literal barrier between the churches. As such, these times of fellowship not only serve as times of learning but also of great rejoicing reunions, with some youth being the only or one of five teens in their local church, finally seeing members of their faith and of their age struggling with the same issues and providing support to one another.

Scope

I began serving in multiple facets for a 100 person Church of Christ in Murray, Utah, during my Architectural education at the University of Utah and was fortunate to observe the differences in their own worship and traditions with my own religious upbringing in Tennessee at a much more conservative church. I wholeheartedly embraced many of their struggles, and set myself towards ministry with their college and youth, where they had much neglect and organization. Finding ways to connect them to nature, as we had a park nearby as well as ample access to the mountains, became my contextual focus. Through hikes and impromptu trips, I began experimenting with acoustical settings and arrangement of the group in order to both observe and appreciate nature as well as be conducive to a loss of self in relation to the their God[8].

This particular church sat in three-quarter round, whereas almost all my own church experiences were in a linear fashion, everyone facing the pulpit, and worshipping only frontally, the sound of the person behind you either helping or hindering. My exposure to this new style of seating intrigued me greatly, especially in context of the scripture so often used to defend Acapella singing, Ephesians 5:19, quoting New American Standard Bible (NASB) version:

19 speaking to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody with your heart to the Lord;

In this arrangement you could almost literally sing towards another person across the room. I began experimenting with my own classes in the full-round, observing both the heightened acoustics which was nothing new but also the heightened awareness that you were being watched from both in the front and in larger, multi-row groups, from the behind, an entirely new sensation from linearly arranged congregational seating.[9]

The center of the circle became sacred space, the space of authority, which is nothing new in history or even in small groups, however for this particular religious group so rarely meeting formally in the round, the void in the center became not only holy, but a place for questions to dwell in the silence, a place to project questions without the need to direct them to someone in particular for an answer.

First Case Study

On the way to speak to a group of young adults from neighboring states at a retreat in Idaho, I began experimenting with ways to both break the tension felt in-the-round as well as relate it to the axis-mundi passing through not only each of the members, but through the space we created when in-the-round, the God of the void if you will.[10]

With college-age Christians, I was able to both explain what I was wanting to try without the adolescent angst or questioning, this group in particular (about 15 young adults) were incredibly nimble and humble in receiving instruction and exploration related to their own faith experience. In addition to simply experimenting with arrangements, I realized that acoustical variations manifest through how they sat in the round was an incredible opportunity. This allowed an experience of completely enveloping my fellow worshippers with sound, something that was so common in the South with thousands of worshippers singing indoors or outside, where by sheer number you could become both immersed and entrenched in sound that literally could move you with acoustical vibrations.[11]

In order to give anything close to that experience, something we missed so much out West, I had to deepen the silence in which a single sound could be heard, making the silence stronger, more powerful, so that the sound of singing could completely envelop you. So instead of trying to test these arrangements indoors, where any number of distractions could ruin the silence, I took the group outside into the center of our camp.

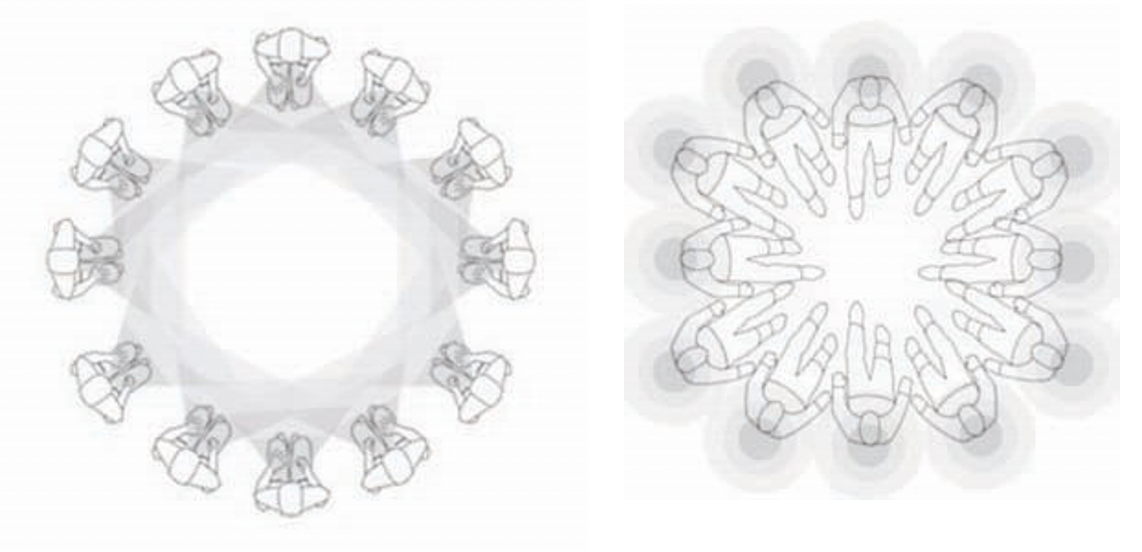

Moving twenty or so college students onto the 4” concrete pad basketball court, I arranged the group in a seated circle facing each other. Four songs had previously chosen to reduce organizational interruptions, to be led with complete silence between each song. The group was seated facing each other (Figure 1), sing one song, pause, and then simply lay down from their seated positions, forming a flat circle with heads on the outer edge at the next song. (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Seated inward-facing arrangement Figure 2. Laying outward-facing arrangement

The group was instructed not to talk, and everything was to be done in complete silence, heightened by the enormous dark sky full of stars in Eastern Idaho mountain wilderness. About a minute of silence would pass once everyone was settled into the new position, and the song leader would begin whenever he was ready and in a good state of mind to begin a joined state of worship.

The seated circular arrangement was very common to the group, as discussed earlier, however when lying down (Figure 2), the immediate projected sound was now directed upward instead of toward another person, and you could faintly hear the person next to you who was further away now by lying down, raising awareness, not only to song timing and on their part[12], but a deeper reflection to whom they were singing.

After this song, and again in complete silence, the group was to sit back up and rotate one hundred eighty degrees to form a seated circle facing outwards (Figure 3), again making it difficult to hear the person next to you, and a deep feeling of loneliness overcome you as you sung not to your peers nor to God above, but to the world of blackness which seem to envelope the worshipper, bringing on the all-to familiar feelings of isolation and fear of the dark unknown, characterized by the woods and the now unfamiliar campgrounds bathed in shadows.

Figure 3. Seated outward-facing arrangement Figure 4. Laying inward-facing arrangement

A moment of silence passing this song, then everyone simply lay down again, this time forming a tight knit circle with the heads in the center, so that you could barely hear yourself due to the sound of the people next to you (Figure 4). The members of the group were all looking upwards at the sky, together, forming a unified and deafening sound, a feeling of closeness that was so unfamiliar to the western worshippers, and a sense of the Almighty’s presence by the uninterrupted millions of stars that you suddenly aware but did not have to face alone as in the previous lying arrangement (Figure 2).

As an aside, when the group was in this final position singing, the concrete started vibrating with the acoustical reverberations of our vocal worship, insomuch as your head began tingling with the vibrations, and it was quite literally a moving experience for us all. The group was completely engulfed in sound, and then immediately following the last note, engulfed in silence under an enormous canopy of stars. It was an incredibly moving worshipful experience, felt both by myself and through testimony of other group members, by most of the group. Worship now had more than just ritual, it had variation in audience, and by such variation a change in purpose for the worship.

Variations on a Theme

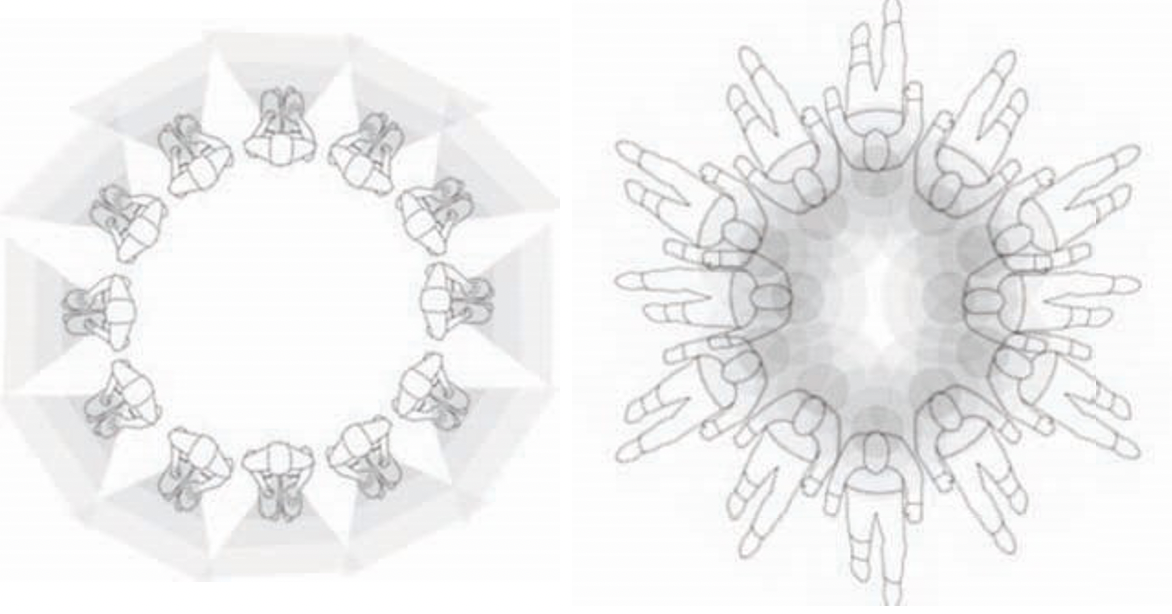

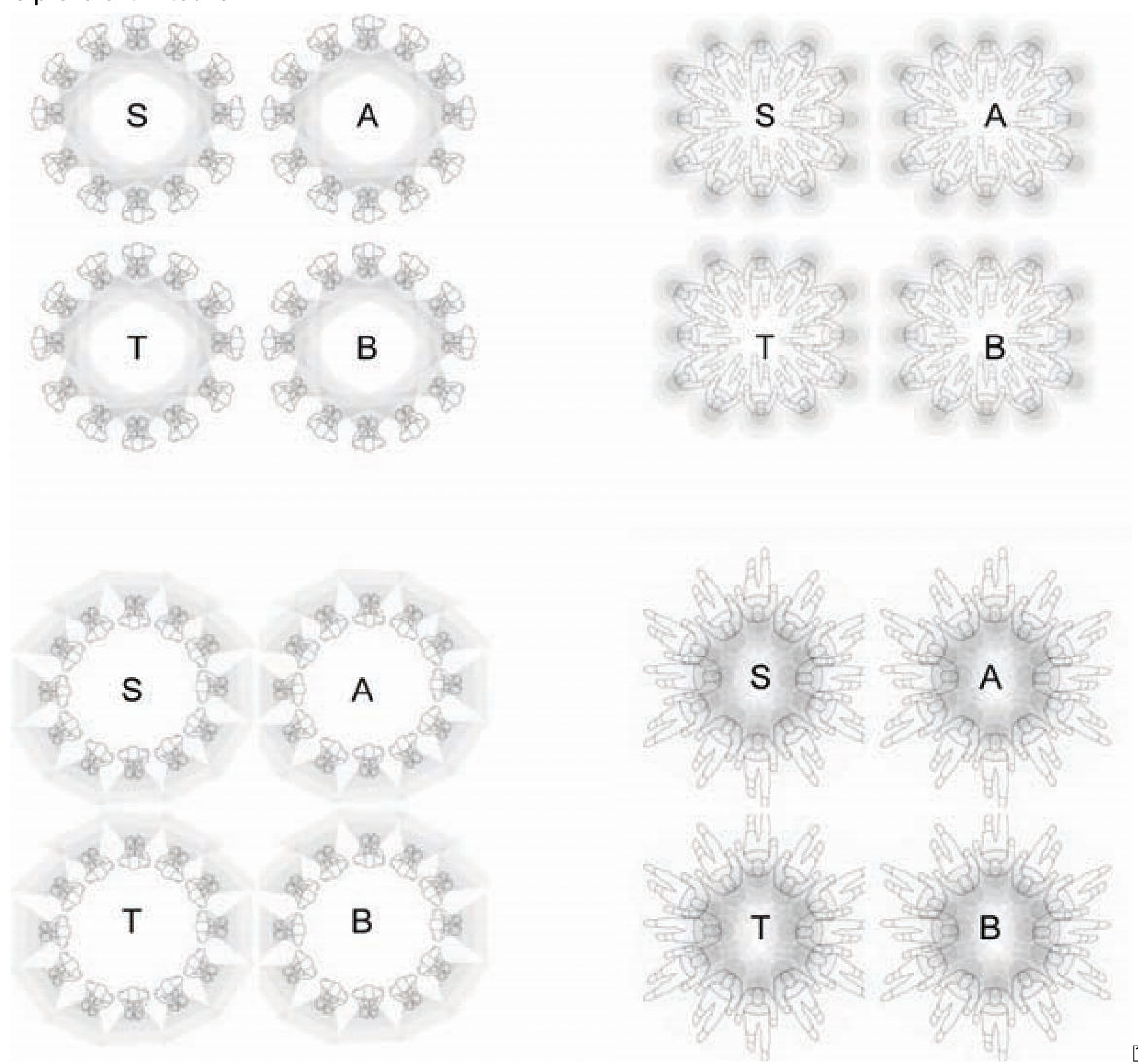

With a great response to the first experiment, I continued with exploration through diagramming on how the spatial organization of both the location of singers as well as the actual position of worship might enhance the worship experience. About a month later, I was given opportunity to work with about 60 teenagers in Colorado, with unrestricted access to experiment and teach. I introduced them to the four position worship, and after an incredible night of worship using it, I decided to start variations on this experiment. The next morning, I divided the 60 teenagers into the formal four-part arrangement groups Soprano, Alto, Tenor, and Bass (SATB). We then went through the same experiment, though this time with the circles adjacent to one another (Figure 5).

This was akin to the ‘hollow square’ arrangement found in sacred harp singing, as a means to reinforce the sound quality of each part, as well as to teach people who did not know their part, as is prevalent in teens.

Figure 5. Adjacent arrangements of worshippers going through the 4 song arrangement arranged Soprano (S), Alto (A), Tenor (T), Bass (B).

Another experiment while at this camp was to nest the different groups. In one particular evening, we had many guests as well as counselors and were under an enormous outdoor pavilion. I began the experiment after it became dark, so without the sky above it was pitch black in the outdoor room. I again grouped the worshippers, but this time also divided them into sub-groups based on camper/counselor which simply corresponded to teen/adult. With these divisions, we then nested the circular groups one within the other, so at some point in time you were seated both incredibly close to someone facing you as well as someone back-to-back to you.(Figure 6.)

This made for complex overlaps when laying down, however the acoustic quality with such density of worshippers, heightened by rain hitting a tin roof, thunder, and flashes of lightning gave way to an incredible experience. We used more than four songs, and after a moment of silence between the songs I also gave instruction on changing the arrangement, so each group had a chance to be in the inner-circle, of particular importance acoustically and religiously.[13]

Figure 6. Nested formation in Position 1, Seated worshippers facing inward/outward

Conclusions

Things are such, that someone lifting a cup, or watching the rain, petting a dog or singing, just singing – could be doing as much for this universe as anyone. Rumi

While so much of our world tends towards complexities, it is the thematic setting of Rumi’s words that remind us that some of the simplest acts can have profound meaning and I expand to say experience. These experiences were just that, a means to bring heightened awareness to something that many worshippers take for granted, and simply to discuss with these young adults the importance of thinking and experiencing who you are worshipping, how you are worshipping, and ultimately why you are worshipping.

There are many physical correlations with the position of the worshipper formally and with the formation and initial experiences/actions of teen faith. Initially, they come either with friends or family and are wholly concerned with an outward facing relationships with others (Position 1, seated facing inward circle, Figure 1). When faced with difficulties or struggles, they then turn to God, entirely on their own with the Creator (Position 2, lying facing up, head outward, Figure 2).

When doing so, they often become self-absorbed, neglecting their fellowship with others (Position 3, seated facing outward, Figure 3). With maturity and hopefully some kind of intervention, they join in fellowship with their peer group, struggling, wrestling with their faith together, but still focused on their own relationship with their God (Position 4, lying facing up, head inward, Figure

4).

Discussions with teens and working with them for four years as a minister, these exercises helped garner a greater sense of purpose and awareness to how they interact within their own youth group but within a larger congregational whole, and a network of communities separated by distance. I have not tried these experiments in the Southeast, and I feel that using a natural setting is imperative to the success of the experience, and there is a vastness wholly belonging to the West. With the rise of technological interruptions and the continued disconnect of people with their spiritual awareness, these experiments only serve as a small step in creating moments where time and space can stand still in order to force us to reflect, ponder, and commune with the

sacred.

[1] Rumi. Things are Such. poem. Translations for this text abound, originally Persian, 15th century

[2] The Barna Group is an independent religious research group, founded in 1984, based out of California and provide research services at the intersection of faith and culture. https://www.barna.org

[3] Note see Kinnaman. You Lost Me: Why Young Christians are Leaving the Chruch…and Rethinking Faith. Baker Books.October 1, 2011.

[4] Many CoC church leaders quote many Biblical passages when instrimental discussions happen, but most cling to Ephesians 5:19, quoting New American Standard Bible (NASB) version: “19 speaking to one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody with your heart to the Lord;”

[5] See the Churches of Christ in the United States report by Carl H. Royster which is renewed annually, using attendance records and now enhanced with online directories and software for demographic data. 21st Century Christian Publishers, 2015.

[6] Tennessee is known as the Belt Buckle of the Bible Belt, of particular importance for the author of this paper, who was raised Church of Christ in Tennessee then began youth and college ministry in Utah, Colorado, and Idaho, where these experiments were held.

[7] The 2003 Civil War action movie Cold Mountain featured sacred harp singing, and then a 2006 movie Awake, My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp, is the first feature documentary about a specific Southern group of Sacred Harp singers, which created an interesting influx of visitors to Church of Christ worship services, although many of the formal aspects of arrangement and order are not used in contemporary Church of Christ worship, however the roots are there and practiced often.

[8] While I understand that there are people of many different beliefs, I am attempting to narrow the focus to Churches of Christ, who are monotheistic.

[9] The main difference here was that now you didn’t feel as if someone was always watching you from behind, but almost awkwardly and constantly making eye contact with someone mouth ajar, singing.

[10] See Exodus 25:19-22: 20: “The cherubim shall have their wings spread upward, covering the mercy seat with their wings and facing one another; the faces of the cherubim are to be turned toward the mercy seat. 21″You shall put the mercy seat on top of the ark, and in the ark you shall put the testimony which I will give to you. 22″There I will meet with you; and from above the mercy seat, from between the two cherubim which are upon the ark of the testimony, I will speak to you about all that I will give you in commandment for the sons of Israel. Many Christians believe that God is dwelling in the ark, however upon close reading he resides above the mercy seat but below the cherubim’s wings, in the empty space. Contemporary study discusses a similar space formed when two people are speaking or worshipping together, briefly eluded to in the New Testament, Jesus speaking in Matthew 18:20: “For where two or three have gathered together in My name, I am there in their midst.” The idea begs the question, is He a third? Or simply dwelling, or existing, in the sheltered void, the space between two, where God resides.

[11] Many references to Sacred Harp singing, from which Church of Christ singing is adapted, references the wall of sound, felt particularly in the center of the hollow square arrangement significant to that style. It is loud, straight-toned, and is sung with an incredible fervor and volume characteristic of rural worship.

[12] Without digressing too much into the technical, most singers, especially in religious chorus or choirs, are assigned a range (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass) which corresponds to a line of music in four-part harmony singing, usually emphasising harmonies, however in sacred harp singing often encouraging dissonant harmonies which create a very particular, almost forlorn and tension-laden sound to the worship atmosphere, heightened by a context of small group in wilderness, forcing sound into the silent night.

[13] Many references in the Bible speak to the organization of the Temple, with the Holy of Holies being the place where the high priest would speak to God, also referred to as the innermost room. See Exodus 26, Ezekiel 25, 1st Chronicles 23, 2nd Chronicles 5:7, 1st Kings 8, and Hebrews 9.