Katherine Bambrick Ambroziak

University of Tennessee, Knoxville aambrozi@utk.edu

It is the way of nature to be used, worked and touched. All of nature here has been touched; the Japanese landscape by centuries of rice cultivation, these mountains by plantation forestry, all are in some way affected, and my art doesn’t hide that fact. We all touch nature

and we are a part of this process of interaction and change, we rely on each other.[1]

— Andy Goldsworthy

Fig. 1 Dandelions and Hole (Yorkshire Sculpture Park Dandelions / newly flowered / none as yet turned to seed / undamaged by wind or rain / a grass verge between dual carriageways / on the way to Bretton), temporary sculpture by A. Goldsworthy, Neat West Bretton, Yorkshire, England, April 28, 1987 (ARTstor Slide Gallery)

Environments of the Found Object is a study of craft and place-making that relies on the associative potential of the found object to reveal qualitative and phenomenological aspects of place and material. The study examines psychologist Paul M. Camic’s 2010 analysis, “From Trashed to Treasured,” that outlines how items originally holding zero value2 may be transformed through the creative process to become appreciated aesthetic objects, artifacts that possess associative and mnemonic meaning. Presenting the works of artist Andy Goldsworthy as an exemplary model for analysis in environmental art, this proposal expands beyond Camic’s traditional limits of what constitutes the found object as generally man-made artifacts to include natural elements, structures, landscapes, and atmospheric conditions.

A blossom in a field blurs with its surroundings – it is a thread in the fabric of our environmental context that rests at the periphery of our perception. As such it holds no inherent value. Yet the blossom has the potential to attain new meaning when it is approached, noticed as singular, plucked, moved from its natural origin, and repositioned through a process of transformation or collage. This process may be as simple as placing it in a new setting or combining it with other elements without changing its physical nature. The focused attention gives it aesthetic value, a level of appreciation that fundamentally changes its nature from mundane to a cherished object.

The blossom unnoticed in the field is the victim of subjective “disinterestedness,”[2] an aesthetic approach to everyday conditions unbiased by personal association. This kind of indifference is common among contemporary societies where worth is determined by functional commodity. Appraisal is intellectualized and often judgement is relatively quick, reliant on visual cues for quantitative valuation. The haptic and more body-oriented sensory systems are comparatively marginalized as organs of assessment. Along with them fall the tangible objects and places that constitute our everyday environments and help to establish personal and cultural identity.[3] Often we are aloof and unaware of their contextual beauties, which for lack of attention approximate zero or low aesthetic value.[4] The question at hand is how we may bring such specialness into focus and grow our sense of appreciation.

Camic: Theories of the Found Object

One approach relates to the described process of discovery where the blossom is selected, removed, and given new status through a creative act which psychologist Paul Camic describes as the Found Object Process. He examined cognitive theory, rubbish theory[5], and studies of art and aesthetics to better understand how interactive and creative experiences with objects play a role in man’s emotional and social development. His study focused specifically on objects of everyday living, which he claimed has the potential to possess “a higher complex or hidden meaning beyond what was seen.”[6] Latent cognitive and associative value are released when the objects inspire a creative response. His findings are similar to accounts whereby reclaimed or found objects are “recognized as emblems of a way of life involving powerful emotional commitment.”[7] This creative process demands subjective attention and aesthetic judgment where personal value is ascribed.

Camic’s research relied on grounded theory, analyzing results from survey questionnaires, to investigate how individuals used and realized value in found objects in their day-to-day lives.

Through data analysis, he identified superordinate categories that provided the supporting structure for an explanatory understanding of found object use. These were discovery and engagement, history and time past, the symbolic and functional object, psychological processes, and ecological affirmation. He reported that “[f]ound and second-hand objects were found to be evocative things that stimulated emotions, acted as mnemonic triggers, became part of a personal reflective account, and were responded to through creative actions that enhanced the aesthetic appeal of the object.”[8]

Though the majority of Camic’s account focused solely on the found object, he foregrounded his argument with a short narrative about man’s primitive instinct to seek out and embellish natural features within his environment – the example given was a projection or indentation within a cave.

“When early prehistoric people recognized a cave’s natural feature as ‘found object’ and incorporated it in a picture, it is possible that the natural feature took on a higher value than if left alone.”[9] This story was told in a single paragraph; nowhere else in his extensive analysis does he reference man’s relationship with natural contexts as qualitatively influential to experience and aspects of human emotional and social development. Environments of the Found Object argues that by extending Camic’s found object theories to natural contexts, be they natural elements (a shaft of wheat, a pinecone, a stone), landscapes (fields, forests, a cliff-side), environmental activities (moving water, breezes), or the perception of environmental stimuli (sound vibrations, temperature changes), we may better understand and apply transformative processes that reveal the qualitative and phenomenological aspects of place and our relationship to it.

Fig. 2 natural element: Wheat Sheaves near King’s Somborne (geography.org); natural landscape: Cliffside, Sydney (courtesy of Joey Hess); environmental activity: Waves, cropped2 (courtesy of Birgit Zipser); perception of environmental stimuli: That Sound (courtesy of Selma Gokcen)

Goldsworthy: Analysis of Process and the Found Environment

This proposal studies the artist Andy Goldsworthy[10] in order to give specific reference to how the found object process, reconceptualized to include environmental and natural elements and forms, achieves the aesthetic valuation and cognitive structures described by Camic and thematically outlined in his superordinate categories. The question is how the artist’s interaction with natural materials and environments affects his emotional judgement, promotes empathy with material and place, and stimulates emotion. Evidence is gleaned from Goldworthy’s written and spoken words, available through published interviews and documentaries, and highlights recurrent material and formal themes found in his art.

Transformation through the Creative Process

Camic categorized two transformative processes, one focused on the object, the other on the finder/maker. Discovery and Engagement is the most direct of the categories. It involves three phases: seeking, the active hunt that involves the thrill of anticipation that brings about emotional arousal, motivation, and cognitive engagement, followed by the moment of discovery which stimulates one’s perceptual field and triggers a sense of satisfaction, and finally, a metamorphosis which occurs when the familiar or assumed use of the object generates a creative response.[11] Throughout this process, there is a subjective focus on the object or material being sought, as well as the place where it is found. The second category, Psychological Processes, describes emotional and cognitive changes to the finder/maker himself. This category suggests that there is an aesthetic reaction to the creative response which impacts mood, memory, and identity.[12]

Every day I’ve gone out I’ve learned a little more about the materials, the places they come from.[13]

In many accounts of Goldsworthy’s seeking, he is described as “foraging,”[14] methodically and purposefully searching for materials that inspire an action. He claims, “Often I go out and don’t have any idea what I’m going to do.”[15] His work is frequently improvisational, discovering unforeseen relations within a place and learning from its “internal aesthetic norms.”[16] He allows himself the flexibility to respond to changing environmental conditions and he even builds them into his work – sunlight affecting how we perceive ice and rising tides stealing nests made of driftwood. Through this process he test the possibilities and limits of materials and gains appreciation for their organic response to their environment.

I don’t think the earth needs me at all, but I do need it. To just go off into the woods and make a piece of work roots me again. And if I don’t work for a period of time I feel rootless. I don’t know myself.[17]

Contemplative in both actions and words, Goldsworthy responds emotionally to his work. It gives him bearing and “roots” him, providing context not just with the place, but with a cultural identity that is understood through place. He is immersed in his surroundings and offers his body to the task. Captions that list the medium of the art often include Goldsworthy’s own physical actions – snow, sun, wind, throws. Actions persuade the body; “behaviors precede emotion;”[18] creativity spawns psychological change.

Material Investment

Materials have associative value to the finder/maker that are linked to personal or communal histories. Identifying the importance of History and Time, Camic claimed that by acknowledging that the found object has a past life, it permits the finder to reflect. “Linking the memories and histories that each object has had for the finder allows for the making up of stories about the lives of the object, thus emotionally imbuing both the object and life of the finder.”[19] Goldsworthy relays several stories about found materials and how they promote an empathetic knowledge of his context. Fascinated by the layers of social history in the bucolic Cumbrian landscape,21 he focuses on structures such as fieldstone walls that speak about an agricultural history and tradition. “People have lived, worked, and died here,” he states, “and I can feel their presence in the places that I work. I am the next layer upon those things that have happened already.”[20] He goes on to speak about the system of walls that symbolize communal ties between farms, territories, and even countries. They are an artifact of the history of the place and represent an ever changing physical, social, political, and economic landscape. “The wall is a line that is in sympathy with its context, flow around the world, veins around the world.”23 An artifact with similar motive is wool. As a product of sheep, wool represent the impact that the animal has had on the landscape which has been cleared through millennium of grazing. “Sheep have left their story behind them in the landscape.”[21]

Fig. 3 Raisbeck Pinfold Cone, Cumbria, 1996, installation by A. Goldsworthy (ARTstor Slide Gallery);

Sheep’s Wool on Drystone Wall, n.d., temporary sculpture by A. Goldsworthy (courtesy of Marie Andrews)

While gathering stone for work, Goldsworthy seeks sources that have already been disturbed and is reluctant to unearth any piece that is naturally set in the ground. He compares taking a longstanding stone to uprooting a tooth, [22] a destructive action. This ethic developed early in his career when he refused to even tear leaves from trees for his installations, but rather “waited for them to be given to him as a passage of time… and the natural process of entropic decay brought them to the ground.”[23] These ideas satisfy Camic’s categorization of Ecological Affirmation, which relates to moral concerns for the environment.[24]

This valuation of found materials comes from an affinity Goldsworthy feels for nature. It is an empathetic response. Natural elements have an innate relation to man – they are within him and they are part of the same. When describing bracken (dried fern stalk), he says it “is a material that

I’ve always enjoyed working with. It is aggressive on the hands. I associate it with bleeding hands.”[25] The color red and its relation to blood is recurrent in Goldsworthy’s work. Blood from his

Fig. 4 Red Pools, detail, exhibited at Galerie Lelong, Winter 1995, installation by A. Goldsworthy, photograph by Larry Qualls (ARTstor Contemporary Art, Larry Qualls Archive)

own hands, red maple leaves, red poppies, and red stone are symbolic metaphors. “Stone is red because of the iron content. It is the reason why our blood is red.”[26] With this statement, Goldsworthy connects inanimate materials to the life of man, considering the material to have the same energy flow. Referencing the category of the Symbolic Object, Camic claims that such attributes enhance memory and provide powerful personal association.

Formal Symbols

Using sensuous forms, various material media, techniques that themselves possess a history, the artist who would present a world is always in dialogue with an existing world.[27]

Goldsworthy scavenges not just for natural materials, but also forms simply derived from nature that offer symbolic and personal meaning. A survey of his work dating back to the 1970s reveals recurrent formal themes that reveal associative potential and reinforce aesthetic valuation. Citing three such forms, we continue to encounter support for Camic’s analysis.

The day after Julia’s death I worked with a tree – a hole in the tree. I see it as a kind of visual entrance into the tree – a black hole containing both life and death. Out of holes comes growth. [This is m]y way of understanding not just death, but absence, the intangible, in the context of a tree that will come back to life.31

Temporary sculptures of holes and crevices, often created from the most temporal of materials, symbolize death and life (or reclamation), the cyclical condition of both nature and man. His cairns, built of found wood, stone, and ice, serve as “markers to [his] journey,” places where he finds attachment and comes to know through the process of his work. He has described them as both guardians, standing and protecting, and as the seed, full in anticipation of life. 32

A river is not dependent on water. We are talking about flow.[28]

Goldsworthy gives formal character to the terms flow and energy with an undulating line that varies in scale and material depending on its context. Specific materials may also convey this idea, such as the blackened end of the bracken which is the result of contact with the earth and is evidence of the heat within the ground, the energy transfer. Finding elements such as this, he identifies with the “energy of a place” and comments about the “tremendous potential here.”[29]

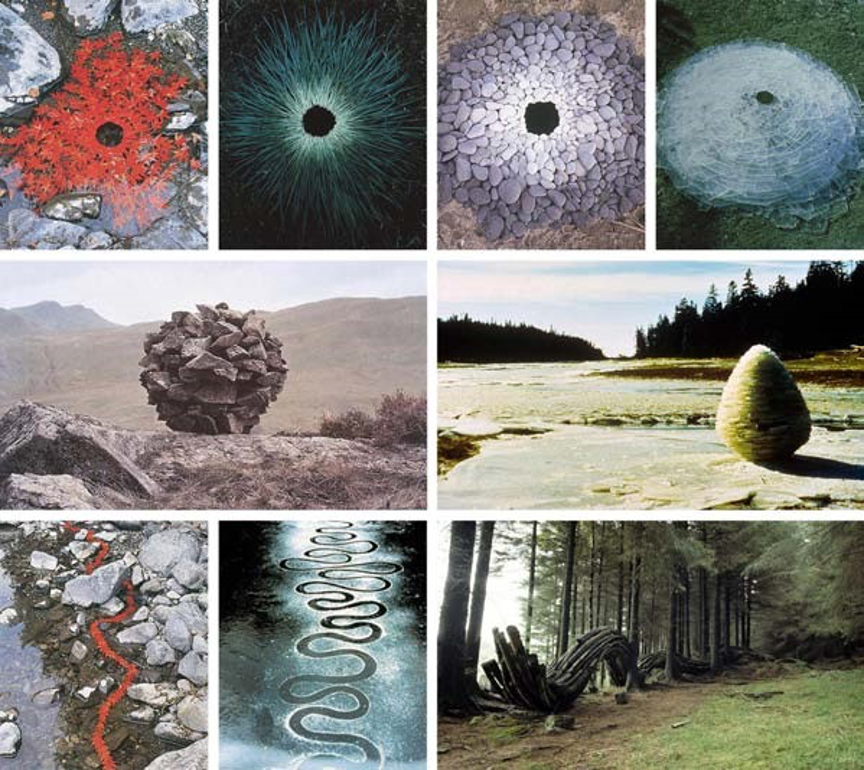

Fig. 5 Japanese Maple and Hole (Japanese maple/…), Ouchiyama-Mura, Japan, Nov. 21-22, 1987;

Grasses and Hole (Yorkshire Sculpture Park Spring Grass/…), England, April 25, 1987; Pebbles around a Hole, Kinagashima-Cho, Japan, Dec. 7, 1987, Ice and Hole (Yorkshire Sculpture Park Worked through the night/…);England, Feb. 20, 1987,temporary sculpture by A. Goldsworthy (ARTstor Slide Gallery)

Stacked Stone, Blaenau Ffestiniog, Wales, June, 1980, temporary sculpture by A. Goldsworthy (ARTstor Slide Gallery); Stacked Ice (Rivers and Tides),exhibited at Galerie Lelong, Fall 2002 – Winter 2003,temporary sculpture by A. Goldsworthy, photograph by Larry Qualls (ARTstor Contemporary Art, Larry Qualls Archive)

Japanese maple/ leaves stitched together…, Ouchiyama-Mura, Japan, Nov. 21-22, 1987, temporary sculpture by A. Goldsworthy (ARTstor Slide Gallery); Flow (Rivers and Tides),exhibited at Galerie Lelong,

Fall 2002 – Winter 2003,temporary sculpture by A. Goldsworthy, photograph by Larry Qualls (ARTstor

Contemporary Art, Larry Qualls Archive); Sidewinder, oblique view in forest, Grizedale Forest Park, Cumbria, 1985,temporary sculpture by A. Goldsworthy (ARTstor ART on FILE Collection)

Conclusion

It’s really the relationship to the common and the ordinary, the things that are around me, the everyday things that are most important to me.[30]

The merit of the found environment is that it provides aesthetic experience[31] that adds cognitive value to our otherwise peripheral view of the world. The processes by which environments are subjectively analyzed and given value “can be understood as a stage model of aesthetic judgments that involve cognitive and affective assessment, emotional arousal, and creative action.”[32] Goldsworthy’s site-specific art and installations focus in on the unique environmental and material conditions with objectives and results akin to those highlighted by the Found Object Process. Through his practice of reclamation, reexamination, reinterpretation, and transformation, he refocus subjective attention to the specialness of place and moments of quotidian perfection.

[1] Fumio Nanjo, “Three Conversations with Andy Goldsworthy: Fumio Nanjo,” in Hand to Earth: Andy Goldsworthy, ed. Terry Friedman and Andy Goldsworthy (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2004), 164. 2 David Gascoygne, A Short Survey of Surrealism (London: Cobden Sanderson, 1936), 169-170.

[2] Margaret Iversen, “Readymade, Found Object, Photograph,” Art Journal 63, no. 2 (2004): 46-47.

[3] Mihály Csíkszentmihályi and Eugene Rochber-Halton, The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1981).

[4] Paul M. Camic, “From Trashed to Treasured: A Grounded Theory Analysis of the Found Object,” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 4, no. 2 (2010): 83.

[5] Michael Thompson, Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979).

[6] Camic (2010), 82.

[7] Mildred Constantine and Arthur Drexler, introduction to The Object Transformed (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1966), iv.

[8] Camic (2010), 88.

[9] Ibid., 81.

[10] This paper assumes a reader’s familiarity with the work of Andy Goldsworthy and does not go into detail regarding specific works of art. Rather, the analysis focuses on the author’s motives and emotional/cognitive responses to his craft process.

[11] Camic (2010), 88.

[12] Ibid., 89.

[13] Kenneth Baker, “Searching for the Window into Nature’s Soul,” Smithsonian 27, no. 11 (Feb. 1997): 96.

[14] Ibid., 94.

[15] Ibid., 95.

[16] Bryan E. Bannon, “Re-Envisioning Nature: The Role of Aesthetics in Environmental Ethics,” Environmental Ethics 33 (Winter 2011): 431.

[17] Andy Goldsworthy Rivers and Tides: Working with Time, directed by Thomas Riedelsheimer (2001; Mediopolis Films, Art and Design / New Video Group, 2004), DVD.

[18] Barbara Myerhoff, et al., Remembered Lives: The Work of Ritual, Storytelling, and Growing Older (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992), 129.

[19] Camic (2010), 89. 21 Baker, 96.

[20] Rivers and Tides 23 Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Baker, 97.

[23] Jeffrey L. Kosky, Arts of Wonder: Enchanting Secularity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 137.

[24] Camic (2010), 89.

[25] Rivers and Tides

[26] Ibid.

[27] Bannon, 426. 31 Rivers and Tides 32 Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Kosky, 137.

[30] Baker, 98.

[31] Paul M. Camic, “Assemblages as Rorschach: Empirical Hermeneutic Aesthetics and the Art Spectator,” in Art and Science, ed. J.P. Frois, P. Andrade, and J.F. Marques (Lisbon: Gulbenkian Foundation, 2004), 228-231.

[32] Camic (2010), 88.