Kyle Dugdale

Yale School of Architecture, New Haven, Connecticut

kyle.dugdale@yale.edu

Figure 1: (above) The “Cathedral of Light” at Nuremberg’s Zeppelinfeld, 1937: described by contemporary observers as an überwältigende Glaubensbekenntnis, an “overwhelming confession of faith.” US National Archives, 532605.

“That field . . . is no longer merely a piece of earth, it is a space in a vast cathedral of light, its dome vaulted high up into the darkness of the night sky. The people are cut off from all earthly heaviness—here, they are all part of a great community, part of an experience that is greater than them. All are focused on a single point, to which all eyes, all hearts, are turned. All have become a part of this power, standing there, a small dot on the grandstand, brighter than everything else: the centerpoint of this great spectacle of light.”

— Wilhelm Lotz, “Das Reichsparteitaggelände und seine Bauten: Verantwortlicher Architekt Prof. Albert Speer, Berlin,” Der Baumeister 35, no. 10 (1937): 309, my translation.

This paper examines a series of spaces conceived, in quite different registers, in response to the global destruction of World War I—whether as immediate reactions to its implacable violence, or as calculated responses exploiting its longer-term effects of isolation, distrust, and resentment. For better and for worse, they were spaces that sought, in their own ways, to heal division, to foster unity, and to establish what can only be described as new patterns of communion. As realistic proposals, the majority of these schemes were conspicuously unsuccessful. One was disastrously effective.

The projects presented offer a range of responses to a singular historical circumstance. They include Hendrik Petrus Berlage’s 1915 design for a Monument to the Peoples (Völkerdenkmal), the 1918 Cathedral of Brotherhood (Dom der Broederschap) for the City of Light (Lichtstad) designed by Frederik van Eeden and Jaap London, and two projects by Albert Speer: his 1939 design for a People’s Hall (Volkshalle) in Berlin, unbuilt; and his so-called Cathedral of Light (Lichtdom) for the Nuremberg Zeppelinfeld, a space designed to nurture the public ceremonies of the Nazi party during the years immediately prior to the outbreak of World War II.

The paper demonstrates that each of these designs drew heavily on the architectural vocabularies of religious encounter, albeit vacated of conventional dogmatic formulations. In other words, they appropriated the familiar features of sacred spaces, without subscribing to the underlying historical commitments that gave those spaces meaning. And if the first two instances aimed to articulate visions of peace and reconciliation, the second pair had altogether different goals; yet they, too, were demonstrably designed to generate experiences that can only be described as spiritual in character. Theirs was a surrogate spirituality, to be sure; but it was by all accounts strikingly powerful and staggeringly effective—its impact recognized even by those who were outside the boundaries of its ambitions. This surrogate spirituality, wielded by architects who were professionally accomplished and highly skilled, sought to strengthen bonds of unity not only between individuals but across society more broadly; and it sought to establish new patterns of ritual and communion—new narratives that are nothing if not religious in their ambitions, invoking a new set of commitments to a newly established authority. But those narratives were fundamentally destructive.

This paper is therefore conceived as a reminder of the precarious relationship between architectural form and spiritual content. It emerges from the material of a recently published book, Architecture After God, further developed through ongoing research into the impact of classical architecture under the conditions of modernity. Its goal is to question the legitimate boundaries of architecture’s adoption of the forms of the sacred; and while its subject-matter is firmly placed on the timeline of architectural history, its implications extend to the present—recognizing that the world is again entering a phase when religious forms are being misappropriated for ends that are not always redemptive, when the vocabularies of spiritual renewal are subject to abuse, and when even the suffering of the global pandemic has been exploited for political profit. It argues that skill, professionalism, and command of historical precedent are insufficient guarantors of an ethical architecture, and that even the architecture of good intentions can be co-opted for destructive ends.It may be easy to concur, with Thomas Berry, that “the universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects”1; but architects cannot ultimately avoid the harder work of confronting an inconvenient truth: that the available patterns of communion are not all equally constructive. What distinguishes true communion from its false counterparts, or the holy from the unholy?—and how can architects, and those who love architecture, best nurture the one while guarding against the other?

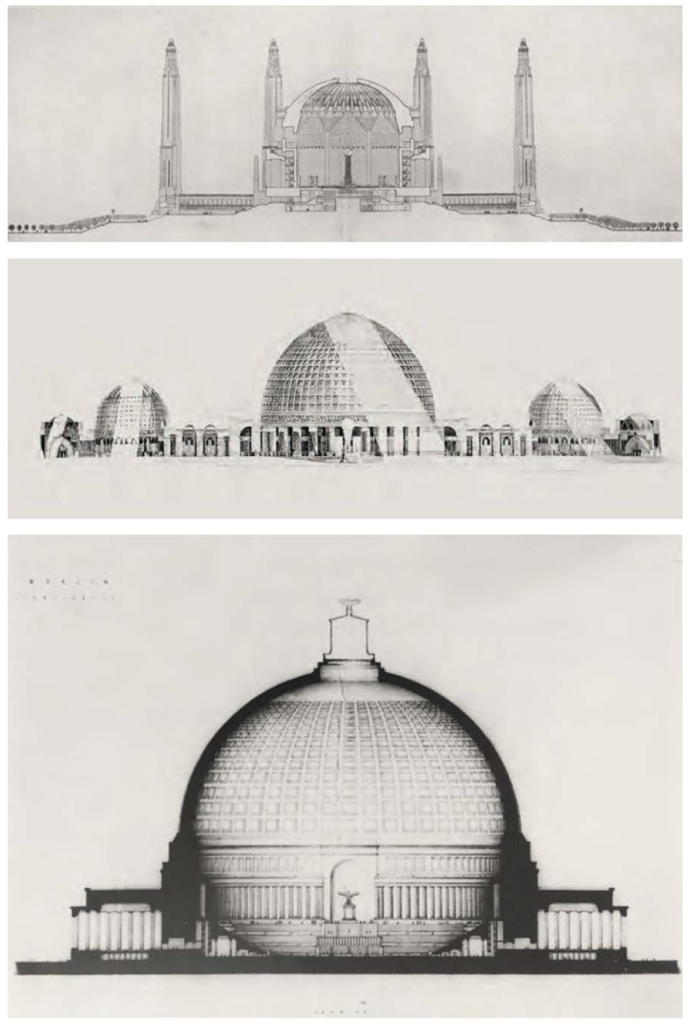

Figure 2: (top) Hendrik Petrus Berlage, design for a Völkerdenkmal, 1915; (middle) Frederik van Eeden and Jaap London, design for a Broedertempel, 1918; (bottom) Albert Speer, design for a Volkshalle, Berlin, 1939.

Hendrik Petrus Berlage, Hed Pantheon der Menschheid: Afbeeldingen der ontwerpen (Rotterdam: Brusse, 1915), 16–17; Frederik van Eeden, Het Godshuis in de Lichtstad (Amsterdam: Versluys, 1921); Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Büro Speer Pläne 2845.

1 Thomas Berry, “Petrochemical Age,” in Evening Thoughts: Reflecting on Earth as a Sacred Community, ed. Mary Evelyn Tucker (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 2006), 96.