Lindy Weston

University of Kent, Canterbury, U.K.

lindyweston@gmail.com

Scholars of architecture, culture, and spirituality are concerned with studying spiritual transcendence, while maintaining traditional research methods.[1] It follows that an historical example is presented in this paper to illustrate the theme of spiritual experience evoked by ordinary things. The specific historical example is Gothic architecture of the twelfth century and the concurrent liturgy of construction. Traditional stone masonry of Gothic architecture is simultaneously tedious and edifying.

This specific time in history (12th Century) is important because the weight of the Christian tradition was concerned with seeing God in the earthly realm. The example of Christ which ordered the Church and Christian society, also ordered the work of the masons. We know of the weight of the Christian tradition from the literature written at the time, and the role Christianity filled in Western Europe after the fall of Rome.

It follows that studying spiritual transcendence in the twelfth century calls for an open inquiry whereby the literature and voices of the past are allowed to speak on their own terms. These terms are described within a religious narrative, and this religious narrative needs room to unfold before us. Ultimately the voices of the past tell us that we live in a mysterious and immense God-given cosmos, and we have been called to participate in this cosmos.

The difficulty of the task is evident when looking at the scholarship of Gothic architecture. Readers are hard pressed to find contemporary literature that allows the voices of the period to speak for themselves. Furthermore, master masons left us no written records from the twelfth century. This is not to say that contemporary literature is completely devoid of value. Far from it. Instead we must be able to understand the recent scholarship and see an ancient Christian worldview before us.

The most ubiquitous understanding of Gothic architecture is given to us by art historian Erwin Panofsky. His articulation of the birth of Gothic architecture has been repeated often in history books.[2] Out of a desire for precision and accuracy, Panofsky isolated the birth of Gothic architecture to one person, and one theological idea. Abbot Suger, we are told, was influenced by Dionysian light metaphysics, and as such wanted more sunlight in the cathedral. God is re-presented by light in Dionysian writings. Hence, Abbot Suger wanted larger windows and less stone, so therefore his theological concepts influenced the birth of Gothic architecture at the Abbey of St. Denis. Somehow sunlight became a metaphor for God, and Abbot Suger wanted more of it in inside.[3]

What may not be readily apparent is the inappropriate language used in scholarship about

Gothic religious texts. For the Gothic thinker, architecture did not merely signify God, but embodied something of God himself. God is present in the Gothic cathedral, and not merely re-presentational. It follows that contemporary habits of thought, which treat religious ideas as metaphorical, prevent an authentic understanding of ancient Christianity. Instead we must, at the least, entertain the idea that God is present in Gothic architecture.

Abbot Suger was influenced by the Dionysian tradition, and a general trend of Christian NeoPlatonism, but there is something far more obvious if we don’t seek to explain Gothic architecture as the concept of one person. What will be explained is Gothic architecture can be better understood as the collective efforts of a religious society who shared a common understanding of Divinity. Instead we can interpret Abbot Suger’s chronicle as just that: a written account of events. It doesn’t make sense to treat Abbot Suger’s writings as having a direct influence on construction decisions when we have no direct evidence of his influence on master masons.

What we do have evidence of, despite the absence of written records from the master masons, is the way in which the cathedral was built.[4] We know the master masons used practical geometry and hand tools to create beautiful buildings. We also know the master masons had a medieval Christian view of the world, and despite illiteracy, would have been immersed in the same religious spirit of the age as Abbot Suger.[5] We also know that Abbot Suger allocated a special place for Christian craftsmanship within his chronicle. In his example we can see the ancient Christian worldview which is sometimes overlooked by contemporary scholarship.

Abbot Suger said this about Gothic architecture:

“Whoever thou art, if thou seekest to extol the glory of these doors, Marvel not at the gold and the expense but at the craftsmanship of the work. Bright is the noble work; but, being nobly bright, the work Should brighten the minds, so that they may travel, through the true lights, To the True Light where Christ is the true door. In what manner it be inherent in this world the golden door defines: The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material And, in seeing this light, is resurrected from its former submersion.” (Panofsky 1979, XXVII)

This quote describes not a re-presentation of divinity, but instead a meeting of divinity through craftsmanship. Abbot Suger is telling us that Divinity is present not only through work, but through crafting material. The matter (i.e. masonry stones) of the cosmos is therefore important, as is the action of humans. It follows that God, man, and the cosmos are vitally important for Abbot Suger and the ancient Christian worldview.[6]

Abbot Suger describes the construction of the Abbey of St. Denis in liturgical terms. Here is where the liturgy of construction is first recorded. Abbot Suger recounts the many important political figures present to lay the stones of the Abbey of St. Denis, and the consecration myth of Christ and the leper at the Abbey of St. Denis.[7] Furthermore liturgy is a term commonly used today to describe the rites and ceremonies of the Church, and this paper suggests it is possible to see a liturgy of construction existed for twelfth century masonry because the process of medieval building was understood as a place of reconciliation with Divinity.[8] Therefore the work of the medieval masons can be seen as Christian public service and Christian public work.[9]

The consecration of the Abbey of St. Denis reveals a liturgy of construction, whereby Abbot Suger chronicled the laying of stones by dignitaries, and even King Louis VII participated in the work. In the presence of these many important dignitaries, holy water was used to prepare the mortar, and in turn many present laid stones in the foundation of the chevet.[10] This story would certainly have been known to the subsequent masons of lower social rank, whom worked on the Abbey of St. Denis.

Another story surrounding the consecration of the Abbey at St. Denis involves the presence of Christ himself. Furthermore, legends of Christ’s presence at the abbey also indicate the extent to which the stones are considered relics. Christ’s presence and consecration of the church is relayed in the legend of the leper, who was sleeping in the church the night before the planned consecration. The leper was woken by the presence of Christ’s light, angels, and St. Denis himself, and all of which participated in consecrating the newly built abbey. Christ simultaneously healed the leper and removed his skin malady to reveal perfection underneath. The scene is attested to by a distorted area on a marble column. Christ affixed the leper’s former skin to the marble column, and thereby created stone masonry that was accepted by medieval man as a relic.[11]

These foundation stories and myths reinforce the status of stones as relics, therefore a concurrent liturgy can be established to exist for all masons.

The theological principle that underlay craftsmanship and a liturgy of construction is uncreated being. As part of the neo-platonic Christian tradition, we can understand the activity of the masons within the medieval Christian cosmology, whose ultimate source is God who creates himself. The uncreated and self-creating aspects of God can be seen in his creation, and humans can participate in God’s creation through craftsmanship. The Christian tradition, which Abbot Suger and the masons are part of, tells us that all being shares God’s being. To say that God is uncreated Being is to establish that God has within himself the explanation for his existence. No external agent or cause brought God into Being, nor any condition. His presence flows from himself, and he has no dependency. Furthermore God is superior to everything else in the logic, order, and reason for his existence. We are reminded of the Christian conception of God, of whom uncreated being plays such an important part, when Rene Guenon suggests the “world is not eternal because it is contingent. In other words it has a beginning as well as an end because it does not contain its principle in itself, that principle being necessarily transcendent with respect to it”.12

Not only is God uncreated, but he is also necessarily so. His being is necessary not only for creation, but for his own existence. He owes no contingency to another, and is the source of creation. The essence of God is his creation, yet God is uncreated.[12] This essential nature of God having no external source of creation provides the basis for knowing anything “in itself”.

God’s essence is to be, and his act of being is his act of being. Furthermore the Latin term, “ipsum esse subsistens”, used throughout the medieval Christian tradition characterises this understanding of God as the subsistent act of existing itself.[13]

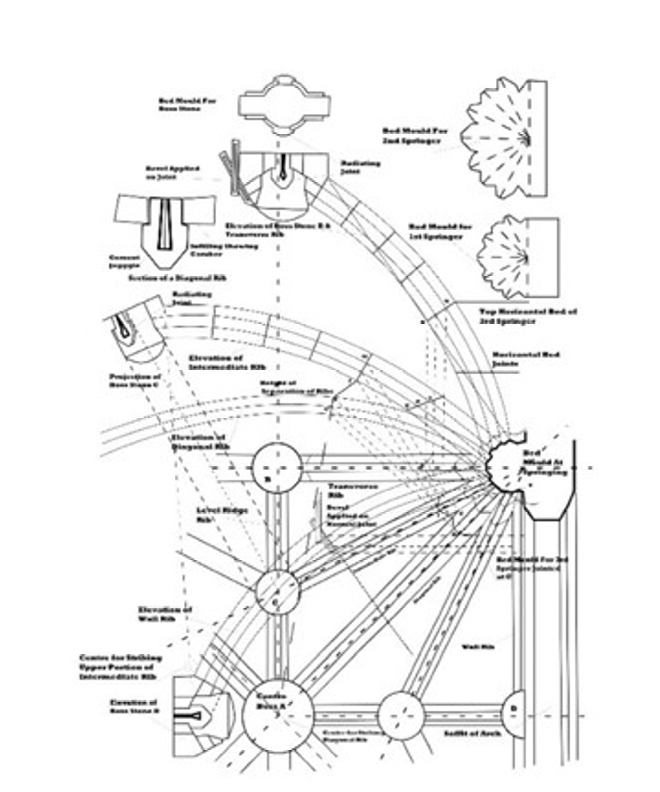

From this fundamental understanding of medieval Christianity we can then see the importance of how the masons worked. The use of geometry and the use of hand tools both demonstrate the application of a medieval worldview in building during the twelfth century. Christian masons saw something important in geometry and craftsmanship.

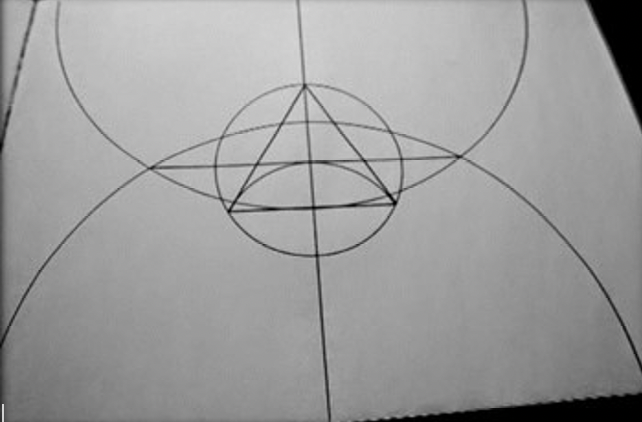

What did medieval masons see in geometry and craftsmanship? The short answer is the masons could see God’s nature in geometry and their work. The use of a straight edge and compass allows for geometrical constructions that generate the templates used for carving stone. Hand tools such as a hammer and chisel are used on stone in a manner that continues the process of creation in a way similar to God’s act of creation.

Understanding how geometry is self-creating requires constructing the same geometrical figures used by medieval masons. Using a straight edge and compass, it is possible to demonstrate self-generation from a single point to triangles, squares, and other shapes necessary for creating templates from which to cut stone with.

Figure 1 Geometrical Constructions, Drawn by the Author

Furthermore the same religious sense of self genesis can be seen in the act of carving stone. The series of drafts by which the chisel removes stone to match the template, is a process where each step relies upon previous steps, and each step generates subsequent steps. Each point in the process of craftsmanship generates each subsequent point.

Figure 2 Laying Out of a Rib Vault, Drawn by the Author from Warland.

Figure 3 Drafting a Finished Stone Profile Using Hand Tools, by the Author.

Bibliography

Barrie, Tom, Julio Bermudez, Anat Geva, and Randall Teal. 2007. “Creating a Forum for Scholarship and Discussion of Spirtuality and Meaning in the Build Environment.” Architecture Culture Spirituality. 1-7. Accessed May 15, 2015. http://www.acsforum.org/ACS_founding_whitepaper_2007.pdf.

Doig, Alan. 2008. Liturgy and architecture from the early church to the Middle Ages. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Ellard, Peter. 2007. The sacred cosmos: theological, philosophical, and scientific conversations in the early twelfth century school of Chartres. Scranton: University of Scranton Press.

Grant, Lindy. 1998. Abbot Suger of St-Denis: Church and state in early twelfth-century France. London: Longman.

Guénon, René. 2001. The reign of quantity & the signs of the times. Ghent, TX: Sophia Perennis.

Helen Gardner, Richard Tansey, Fred Kleiner. 1996. Gardner’s art through the ages. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Ivanovic, Filip. 2011. Dionysius the Aeropagite between Orthodoxy and Heresy. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

James, John. 1990. The master masons of Chartres. Sydney: West Grinstead Pub.

Jones, Lindsay. 2000. The hermeneutics of sacred architecture: experience, interpretation, comparison. Cambridge, MA: Distrubuted by Harvard University Press for Harvard University Center for the Study of World Religions.

Painter, K. 1999. “The Water Newton Silver: Votive or Liturgical?” Journal of the British Archaeological Association (CLII): 1-23.

Panofsky, Erwin. 1979. Abbot Suger On the abey church of St.-Denis and its art treasures. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Warland, Edmund George. 1929. Modern practical masonry: a comprehensive treatise. London: B.T. Batsford.

Wildiers, N.M. 1982. The theologian and his universe: theology and cosmology from the Middle Ages to the present. New York: Seabury Press.

Wilkinson, Philip. 2010. 50 architecture ideas you really need to know. London: Quercus.

[1] Barrie, Tom, Julio Bermudez, Anat Geva, and Randall Teal. 2007. “Creating a Forum for Scholarship and Discussion of Spirtuality and Meaning in the Build Environment.” Architecture Culture Spirituality. 17. Accessed May 15, 2015. http://www.acsforum.org/ACS_founding_whitepaper_2007.pdf.

[2]Panofsky, Erwin. 1979. Abbot Suger On the abey church of St.-Denis and its art treasures. Princeton: Princeton University Press; Helen Gardner, Richard Tansey, Fred Kleiner. 1996. Gardner’s art through the ages. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College Publishers; Ivanovic, Filip. 2011. Dionysius the Aeropagite between Orthodoxy and Heresy. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

[3] Wilkinson, Philip. 2010. 50 architecture ideas you really need to know. London: Quercus.

[4] James, John. 1990. The master masons of Chartres. Sydney: West Grinstead Pub.

[5] As regards what follows it must be remembered first that in late antiquity books were expensive and rare, that memory played a far greater role in all culture than nowadays, that much literature, including large parts of the Bible, was known by heart, and consequently the use of a single word would act as the reminder of whole swathes of scripture and liturgy.” Painter, K. (1999), ‘The Water Newton Silver: Votive or Liturgical?’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association, CLII, (page, 1-23).

[6] 1.) Wildiers, N. M. 1982. The theologian and his universe: theology and cosmology from the Middle Ages to the present. New York: Seabury Press., (page 23-25, 31, 110), 2.), Ellard, Peter. 2007. The sacred cosmos: theological, philosophical, and scientific conversations in the early twelfth century school of Chartres. Scranton: University of Scranton Press., (page 209-237).

[7] Doig, Allan. 2008. Liturgy and architecture from the early church to the Middle Ages. Aldershot, England: Ashgate.

[8] Jones, Lindsay. 2000. The hermeneutics of sacred architecture: experience, interpretation, comparison. Cambridge, MA: Distributed by Harvard University Press for Harvard University Center for the Study of World Religions. Despite a focus on South American examples and emphasis within Jones’s previous work, his morphology can certainly be helpful as a heuristic guide when attempting to interpret sacred architecture many years preceding modernity. To come to an appropriate understanding of medieval Christian architecture for example, it is important to understand the religion which existed at the time. The foundation of Gadamerian hermeneutics informs Lindsay Jones throughout the exploration of sacred architecture by providing a means to encounter a way of looking at the world that is inaccessible for many scholars today.

[9] “A rite is, etymologically, that which is accomplished in conformity with order, and which consequently imitates or reproduces at its own level the very process of manifestation; and that is why, in a strictly traditional civilization, every act of whatever kind takes on an essentially ritual character.” Guénon, René. 2001. The reign of quantity & the signs of the times. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis., (page, 338).

[10] Suger, Erwin Panofsky, and Gerda Panofsky-Soergel. 1979. Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St.Denis and its art treasures. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p.101.

[11] Grant, Lindy. 1998. Abbot Suger of St.-Denis: church and state in early twelfth-century France. London: Longman. 12 Guénon, René. 2001. The reign of quantity & the signs of the times. Ghent, NY: Sophia Perennis, (page 48).

[12] The word ‘creation’ is being used as a verb and a noun.

[13] The essence of God is His existence, that he is ipsum esse subsistens.