Joshua Zinder

Joshua Zinder Architecture + Design

jzinder@joshuazinder.com

Introduction

Design-adept and solutions-oriented, architectural practice leaders look for ways to bring likeminded partners together to create positive, long-term social change where they live and work. They also want to communicate widely the potent role that design can play in addressing various social issues: inclusivity, accessibility, homelessness, refugeeism, food insecurity, poverty, sustainability and more.

The challenge for architects is to find a way to bring together community leaders, nonprofit organizations, public officials and entities, private stakeholders, and others to raise awareness of social issues, and the potential for bringing design thinking to bear to illuminate new approaches and solutions. In this presentation, we will explore the experience of co-organizing a municipality- wide, multi-day event undertaken in Princeton, New Jersey, and share how that event, Sukkah Village 2021, offers a model for practitioners to leverage their skillsets in the service of social progress by partnering with faith-based nonprofits, worship communities, and compatible organizations that wish to support the effort or that stand to benefit their cause, or both.

Precedent

Events that combine design and spirituality are relatively common, and almost always associated with traditional holidays. Common examples include gingerbread house building and tree- trimming events for Christmas, Easter bonnet crafting – often combined with a “parade” – and various Halloween-related activities from pumpkin-carving and costume parties to full-scale haunted house attractions.

In 2010, New York nonprofits Reboot and Union Square Partnership teamed to create an exciting new public design competition: Sukkah City. Architects submitted plans for various types of sukkahs, the temporary hut-like shelters that figure into traditional observance of the week-long Jewish festival Sukkot. Each design had to meet certain strictures enumerated in traditional observance, such as “walls must be at least 10 handsbreadth tall,” and “the roof must be thick enough to shade those sitting inside, and thin enough so stars are visible at night.”

A jury of esteemed design professionals and critics determined twelve finalists, which were built and displayed in Union Square’s greenspace for the public to admire, enjoy, and vote on. The winner was declared the “people’s sukkah” and remained standing for the entire Sukkot holiday. Sukkah City was especially notable for communicating to the public how design can communicate meaning. As noted, architecture critic Justin Davidson wrote:

“Anointing the winner…is almost superfluous; what matters is that for a short time, one of Manhattan’s few town greens will host a conclave of meaningful structures, created not as curiosities but as rest stops for the soul.” 1

Sukkah City organizer Jonathan Foer emphasized the connection between spiritual tradition and social issues: “The sukkah is a space to ceremonially practice homelessness…an architecture of both memory and empathy—memory of the huts the Israelites dwelled in…and empathy for those who live today without solid shelter.”

Background

Inspired by Sukkah City’s impact and resonance, Sukkah Village 2021 reimagined the design- oriented event as a local celebration and a call to action rather than a competition, emphasizing the role of community in social change and the power of design to inspire and illuminate.

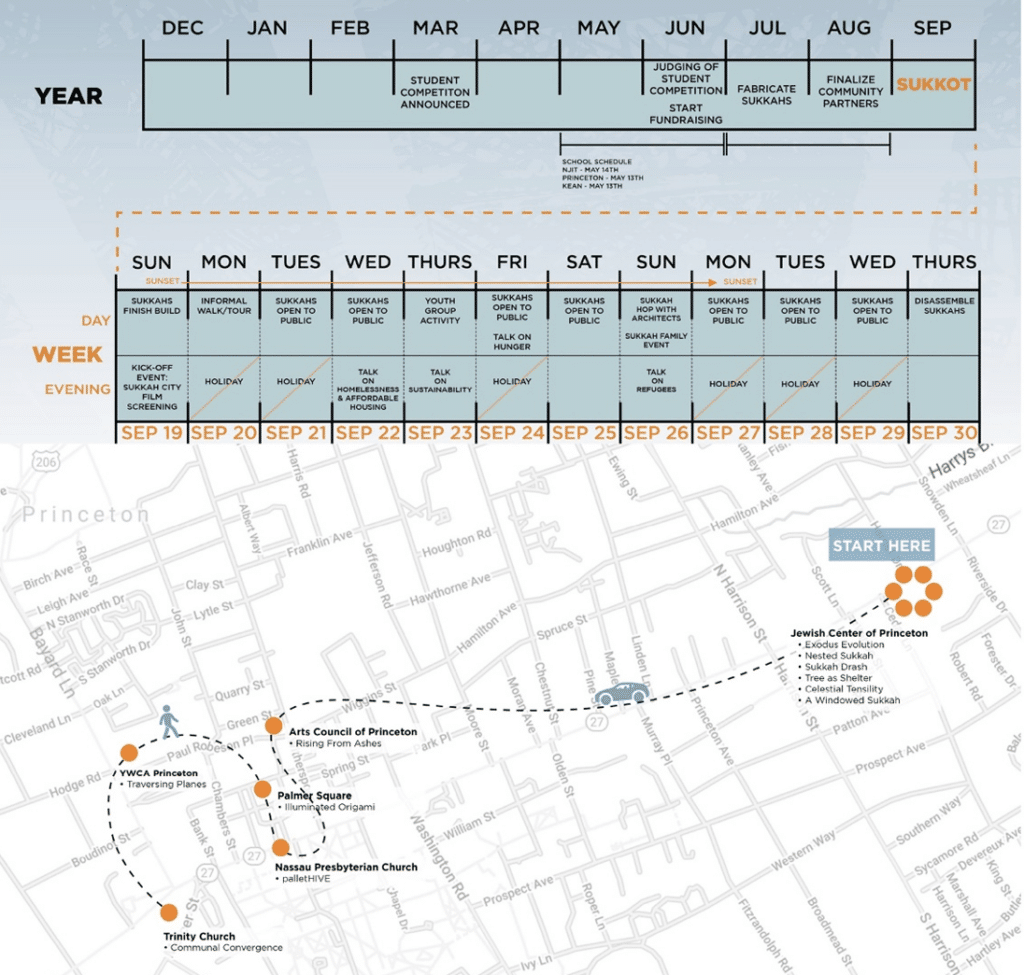

Fig.1 Schedule and proposed site map, from planning meeting presentation for Sukkah Village 2021 participants and sponsors (ã JZA+D)

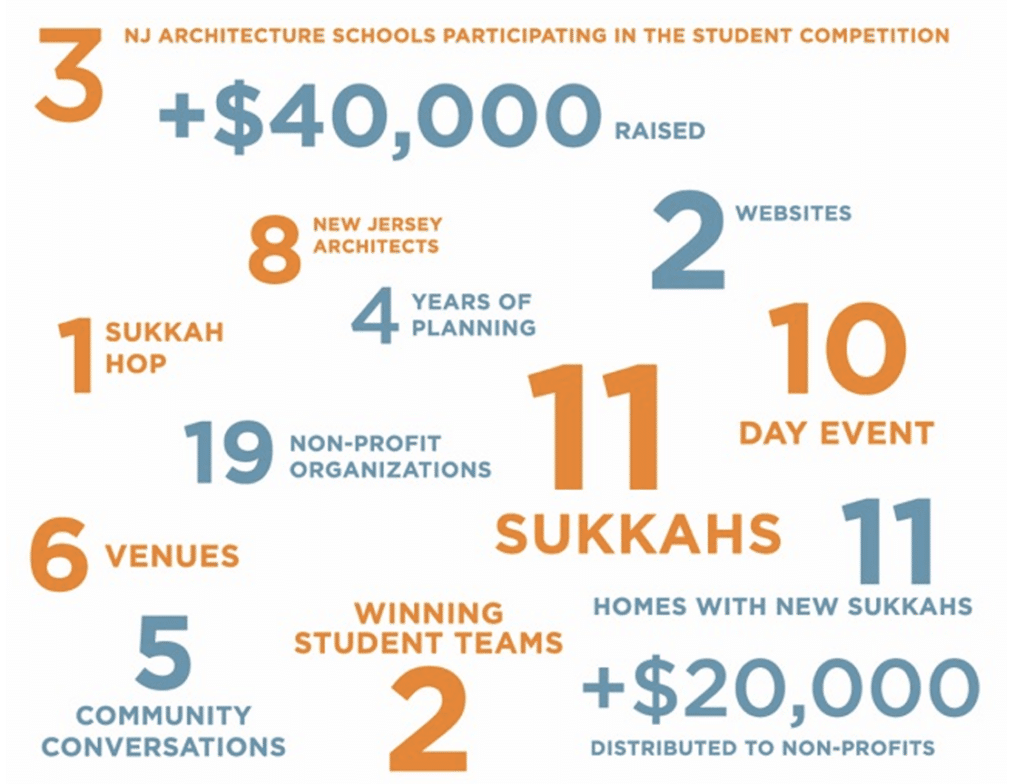

Led by integrated design firm JZA+D in partnership with the Jewish Federation of Princeton Mercer Bucks, the organizing effort focused first on enlisting sponsors, including AIA New Jersey and the Municipality of Princeton, and nineteen participating nonprofit organizations, including the Jewish Center of Princeton NJ, Arts Council of Princeton, Send Hunger Packing, Trinity Church, and United Way of Greater Mercer County. Contributions ranged from direct funding to service provisions, volunteers, and locations for visitor-accessible sukkah displays and related events and activities.

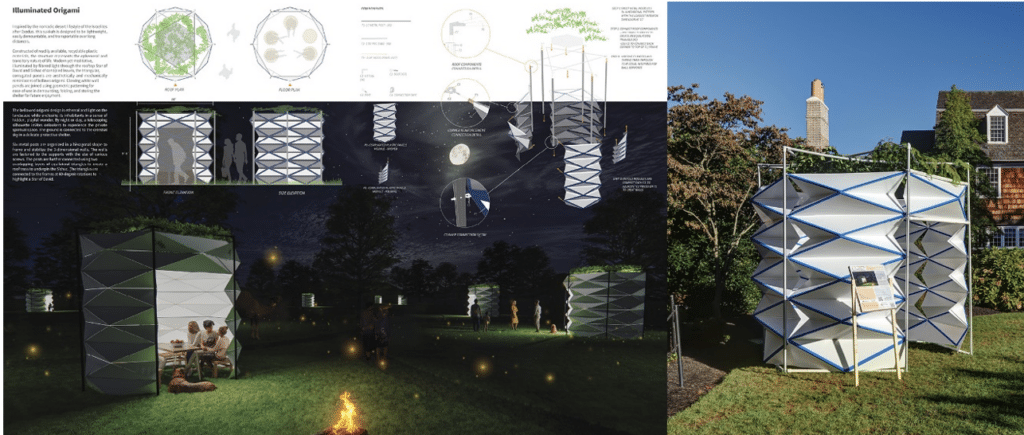

The organizers engaged eight architecture firms to design and build (and ultimately donate) imaginative sukkahs, with two college-level student teams selected through a statewide competition contributing likewise. Provided nominal stipends to cover some costs, each design team was partnered with a non-profit which they could incorporate into their design. Required to follow the strictures enumerated in Jewish tradition, including being sustainable, the designs also had to adhere to additional parameters related to public safety as well as reuse, particularly ensuring ease of mounting and demounting for the lay person – this last instruction critical in the plan to auction off the built sukkahs to benefit the contributing non-profits.

Fig.2 Design board for one of eleven original sukkahs (ã JZA+D)

Erected for public display on several Downtown Princeton sites, the shelters stood for the entirety of the Sukkot festival holiday, serving to bring attention to a variety of issues including hunger, homelessness, refugeeism, and sustainability. Sukkah Village participants and organizers hosted related events including a panel discussion series, a film screening, walking tours, family crafting activities, and a day-long “Sukkah Hop” where design team members stationed by their built sukkahs greeted the public and answered questions. At the close, eleven sukkahs were put up for auction online, raising over $20,000 to benefit the nonprofit organizations who participated.

Effects and Impact

Sukkah Village 2021 ultimately attracted hundreds of locals and visitors to Downtown Princeton to view the outdoor displays and participate in the various scheduled activities. Local news press as well as design media covered the event: The Architect’s Newspaper wrote that, “Although Princeton’s Sukkah Village comes over a decade after [Sukkah City] the pressing social issues… are more salient than ever,” and adding, “Thematically, these issues tie in squarely with Sukkot.”2

The festival also appeared in Bloomberg CityLab, Princeton Town Topics, and multiple Judaic- interest publications including Hey Alma, Jewish Link, and Jewish Telegraphic Agency. The feature in Hey Alma noted in particular the secular and interfaith aspects of the festival: “We appreciated that sukkahs were erected in secular and religious spaces alike, and not just Jewish ones either. Though the Jewish Center of Princeton houses six of them…others are located at the Arts Council of Princeton, the YWCA, and at two churches.”3

Fig.3 Aerial view of “Sukkah Hop” (ã JZA+D)

To understand the impact of the festival more fully, JZA+D conducted an informal survey of participating community organizations’ leaders, professional design team members, and the student sukkah designers. Asked “How would you rate the amount of exposure the event brought to your organization/cause?” 10 of the 11 responding organizational leaders indicated either “satisfied” or “very satisfied.” The same number indicated that Sukkah Village had both short- and long-term impacts on their organization, ranging from “a little” to “a great deal” and including increases in requests for information, monetary donations, and volunteerism. Ten respondents also said they would likely (or very likely) participate in Sukkah Village again.

Asked for comment one respondent noted, “Building connections between Judaism and other members of our community is a plus,” and another that Sukkah Village “achieved wide-spread community engagement,” suggesting that progress had been made toward the goal of reinforcing community-based solutions. In the space provided for ideas on doing things differently in future iterations, responses included:

- additional focus on specific issues

- adding more activities to the festival roster

- congregating all sukkahs on a single site

- “more lead time to direct foot traffic to the displays.”

Design team leaders responding likewise overall praised the event, indicating that the practical design challenge served as a team-building exercise that fortified existing firm culture. Some criticisms offered ideas for better communication and organization – one student team shared an experience of challenges related to the stipend timing, which receiving the funds earlier would have alleviated. All designer respondents indicated that they greatly appreciated the unique opportunity to address social issues and galvanize community around discussions of solutions, as typified by this comment from KSS Architects:

“[I]t’s really important to our firm that we do what we can to contribute to/participate in the community, and this was the perfect opportunity for that…it was great to be able to think about areas of social responsibility that aren’t necessarily relevant in our own work typically.”

Conclusion

Sukkah Village 2021 can serve as a practical roadmap for architect-led multi-stakeholder partnerships creating large-scale design-focused events that engage, delight, illuminate, and inspire. Passionate advocates for a variety of causes can draw on the experience to create new, widely impactful events in their region, championing charitable and nonprofit organizations that tackle major social issues with architecture and design serving as a catalyst for change and bringing wider attention to – and deeper understanding of – those issues and the potential for design to inform solutions. The hope is that the tools and methods presented and the lessons learned provide inspiration for other such events nationally and globally as well as opportunities for improving on conception and execution to make the most of the event and capitalize on a “long tail” to sustain fundraising and continued awareness and volunteerism – buoyed by the work and public relations and communication efforts of participating peers, nonprofit partners, community leaders and event attendees.

Fig.4 “Sukkah Village By The Numbers”

1 Justin Davidson, “Sukkah vs. Sukkah,” New York Magazine, September 9, 2010, https://nymag.com/arts/architecture/features/68057/

2 Matt Hickman, “Princeton’s Sukkah Village 2021 sheds light on pressing social issues,” The Architect’s Newspaper, September 22, 2021, https://www.archpaper.com/2021/09/princetons-sukkah-village-2021- pressing-social-issues/.

3 Chloe Sarbib, “In This Small New Jersey Town, Sukkahs Pop Up in Unlikely Places,” HeyAlma.com, September 23, 2021, https://www.heyalma.com/in-this-small-new-jersey-town-sukkahs-pop-up-in-unlikely- places/.