Clive Knights & Travis Bell

Portland State University, Portland, USA knightsc@pdx.edu, btravis@pdx.edu

“Earth, who came to us

Eyes closed

As though to ask

For a guiding hand.” [1]

Today, under the auspices of a weak and diluted notion of ‘design’ conceived predominantly as a problem-solving activity, architectural practice is almost blind to the depths of human being, desensitized and methodologically paralyzed by systematic procedure and codified action. The artfulness of all human making, cognizant of the original, encompassing implications of the Greek term ‘techne,’ has suffered unprecedented fragmentation and reduction in the industrial era, the arts being extracted from everyday life and mollycoddled inside the rarified environment of the museum, theatre and concert hall.

Since everyday life is where we get serious things executed efficiently with technical expertise attuned by the rigors of mathematics and logical process, the excesses of art have been, for the most part, edited from our habitual lives. The multitude of things that humans make have been cast into parallel, dichotomous universes, either swallowed up into the purposefulness of the mundane, or set aside as devices of aesthetic pleasure, in both cases divested of the capacity to connect us to the fullness of a world bounded by horizons of transcendence. We have made the former group of artifacts too busy, wrapped up in assisting us in getting things done; while letting the latter collection become lazy, too self-referential in an effete concern for nothing but the purposelessness of aesthetics. In any case, the products of both are subordinated to a system of artificial exchange-value, a single, leveling immanence that drains the ontic depth from each towards the shallowness of merchandise. Why can’t shoes and paintings and eaves once again be spoken of as equally artful endeavors, each an opportunity for metaphoric revelation of what it is to be human through the manual dexterity of our imagination, where the activity of making each is once more an act of poeisis?

In response to the conference ambition to address “the spiritual value of the highest human capacities for making,” the authors propose a scripted dialogue that will exercise ethical questions through the conference lens of ‘craft’. Kearney reminds us, “’Spirit’ is a very capacious category that, at times, can mean anything and everything. But for the most part it means something, and indeed something important. We meet many in our secular age who are still hankering after ‘something’ – they know not quite what – however that may be defined. This is often referred to as a ‘spiritual quest’.”[2] In recognizing something perpetually missing from, or incomplete in, our lives can we earnestly set out to make it? Do we fill in the gap with an artifact, or do we answer the lack with action and get crafty? Kearney goes on to suggest that the spiritual is not necessarily religious and, importantly, differentiates the spiritual from the sacred, which, he argues, “resides somewhere between the spiritual and the religious. It differs from the spiritual in that it is something you find rather than something you seek. It is ‘out there’ somewhere, rather than ‘in here,’ so to speak. It is there before you are aware that it is there – before selfawareness, before consciousness, before epistemology. We do not cognize the sacred, we recognize it.”[3]

Kearney has characterized the sacred as the embodiment of radical otherness, and we will animate the conversation at the symposium by exploring the degree to which human making might draw primordial impetus from the outward dynamic of a human search for more (the spiritual), matched by the incoming dynamic of the world’s capacity to answer the call with content extending beyond the reach of the skillful hands of the craftsperson (the sacred). LeroiGourhan states, “The human hand is human because of what it makes, not of what it is,”4 but what characteristics of its action and its facture might hold a revelatory capacity for correspondences between the spiritual, which we search for, and the sacred, that we discover?

The possibility of such profound correspondence has perhaps been insightfully legitimized in the making of architecture by Le Corbusier in terms of the ‘ineffable,’ by Hejduk, channeling Benjamin, as the ‘aura’ of a work, and perhaps also by Zumthor’s ‘atmosphere.’ How do you make what can not be fully anticipated, where maximized prediction and control (exercising the post-Enlightenment ideal of absolute freedom to decide) are relinquished for extemporal possibilities, not free to impose but rather, free to respond, an engaged freedom in action, improvisational, participatory, conditioned by the contingencies of a world not of our making. How far can we reach with manipulative skill before we must confess to a limit by acknowledging the surplus that erupts from the materials in our hands? How often those who craft things are frustrated by the material they handle that refuses to surrender, taking its own course, ignorant of human intention as it thwarts every effort to bring it under control. What claim does matter make upon us and what claim do we make upon it in return?

Tallis exalts the human hand as the key to self-awareness by virtue of both its indeterminacy and its sensitivity. With the hand we can touch our body and first learn that it is ours, differentiated from all that is not, from an-other, from nature. As such, the hand is the well-spring of a sense of selfhood, of subjectivity, and of agency. With the physical versatility, and hence practical aptitude of the hand, the primordial proto-tool, humans can manipulate the stuff of the world, take up what we find and modify it towards something else.[4] But why? To promote survival? To stimulate bodily pleasures? To make concrete what we know? To make concrete what resists our knowledge? What really matters in the manipulation of matter? How do we enter into meaningful partnership with material through acts of craft as against the monologue of technical domination? What is at stake in improvised making (Ingold), over calculated manufacture? Is there an eschatology of craft, a redemptive dimension to the act of making in the face of our mortality (Steiner); what of incarnation (Kearney), living flesh in communication with flesh (Merleau-Ponty)? What is the value of approximation versus exactitude, risk in the act of making rather than prognostication and certitude (Pye)?

As an interlocution between two handymen (the co-authors, conversing), two individuals passionately espousing, sometimes incompatible, worldviews, a two-person ‘agon’, a scripted performance devised to present alternating perspectives, we will aim to bring to the foreground nuanced positions on the cultural import of craft, hoping to offer insight into the virtue of both the activity and its finished products. We offer a prelude to a conversation to follow……

“What is completion? A small-scale model of transcendence given to someone who without this gift would just have been himself. And being yourself alone just isn’t enough. How dull to be nothing but yourself.” [5]

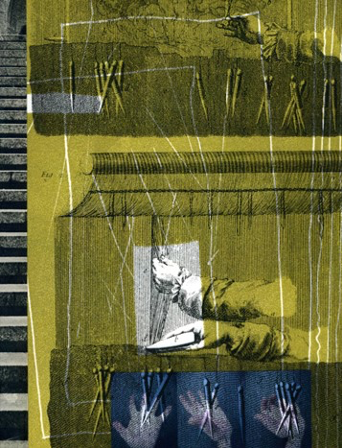

Manipulanda, collage, 2014, Knights

[1] Yves Bonnefoy, from “Let this world endure” in The Curved Planks – Poems (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2001) p41

[2] Richard Kearney, Reimagining the Sacred (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016) p15

[3] ibid 4 André Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 1993) p240

[4] Raymond Tallis, The Hand: A Philosophical Inquiry into Human Being (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003)

[5] Adam Zagajewski, Another Beauty (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1998) p138