Jeff Dardozzi

LivingStructure, Brandon, Vermont

jdardozzi@livingstructure.org

Introduction

This research explores the concept of theodicy (affirmation of the divine in the face of evil) in the secular context of designing/building through the COVID pandemic (Belk, Wallendorf and Sherry, 1989, 1)

Sociologists of religion have long noted the secularization of religious behavior concomitant with the sacralization of the secular. Keeping this observation in mind, this presentation explores the social dynamics and the structure of experience in a modest residential build project by a small design/build collective working in the high risk, constrained and fragile circumstances of the pandemic.

While for much of society the impacts of COVID were wholly negative, the experience of building through COVID has been life-affirming (theodicratic). Even in the presence of death and the overwhelming fear of contamination, social bonds flowered and grew, commitment to practice renewed, and a sense of clarity in purpose and connection to place strengthened. The experience of the artifact as the expression of something far more than the sum of its parts was made concrete.

Through the examination of process and organization as well as unintentional practices and alternative approaches to working the built environment, the presentation maps our secular practices to the ‘properties of the sacred’ as synthesized by consumer behavioral scientists Belk, et al and based on the writings of Durkheim, Eliade, and others.

Background

LivingStructure is, formally, a low/no profit design/build company that focuses on small budget, residential dwellings in rural spaces. We have been active for over twenty-five years. One side of our mission is to facilitate low cost self-built housing utilizing traditional communitarian and rural economic models coupled to social and material ecologies that lie outside the singular logic of market economies. The other side of the mission is to keep love alive in the act of building by maintaining a high level of agency, improvisation, communitas and affection for the work, the artifact, and the people who grant us the privilege to be who we are. We also live collectively on one property so our work lives are woven into our personal lives. There is no collective religious practice.

The COVID pandemic was a unique experience for many. Much of the experience appeared to be adverse and traumatic: the loss of loved ones, the loss of interpersonal intimacy in everyday life, the untethering of routine and habit. The sudden isolation and limits to freedom of movement and action challenged all. The overwhelming fear of contagion reshaped attitudes, behaviors and

norms. The pandemic also disrupted the economic life of the world. In the realm of construction, the industry experienced remarkable levels of labor shortages, inflation and supply chain disruptions that suspended or terminated projects large and small.

The pandemic also ruptured the normalcy societies tend to work very hard to maintain. A normalcy that, for many of our clients and crew, generates negative emotional responses to social and material conditions that are largely imposed by that normalcy. As a result, this rupture created a new kind of space in people’s lives that they had rarely, if ever, experienced before – unstructured time. Lives were no longer compressed into exhausting schedules of tasks, objectives, and goals remediated with the consumption.

This played an important role in both providing the space to reflect as well as the space to commune which allowed a project that would be difficult to realize under the ever mounting obstacles. We found that the nature of the way our work is organized shielded us from these obstacles to a large extent, which not only served to provide for our material survival, but also affirmed the values and meanings that frame our work.

Sacred Properties Found

LivingStructure’s methodology, if there is one to be found, lies in a long concatenation of adverse feelings to social conditions that often dictate the form and content of life on and off a building site. The methodology could readily be described clinically as a personality disorder if the feelings were not as socially pervasive as they are.

Most of these responses appear ad hoc, although some are obviously reasoned. However, formal linkages to the sacred were never connected until the space of the pandemic led to the incidental reading of Eliade and Durkheim as well as the interpretations of Belk et al., and with it the realization that many of the things we find ourselves doing may be grounded in a quest for the divine in everyday life and the presence of the divine may serve to strengthen social bonds in the face of adversity.

The ‘properties of the sacred’ are briefly detailed below and interpreted through the lens of how we design and build:

Hierophany

There is a belief that a building reveals itself through a series of events no one has control over. Decisions are often in situ and ad hoc and, as is often the case, material things, ideas, people seem to always appear on cue, especially when evoked.

Kratophany

Walking a fine line between success and failure as both are transformative forces to be feared.

OppositiontotheProfane

The chemistry of a build is easily profaned if someone’s presence is demarcated solely by the arms length transaction and prescribed roles.

Contamination

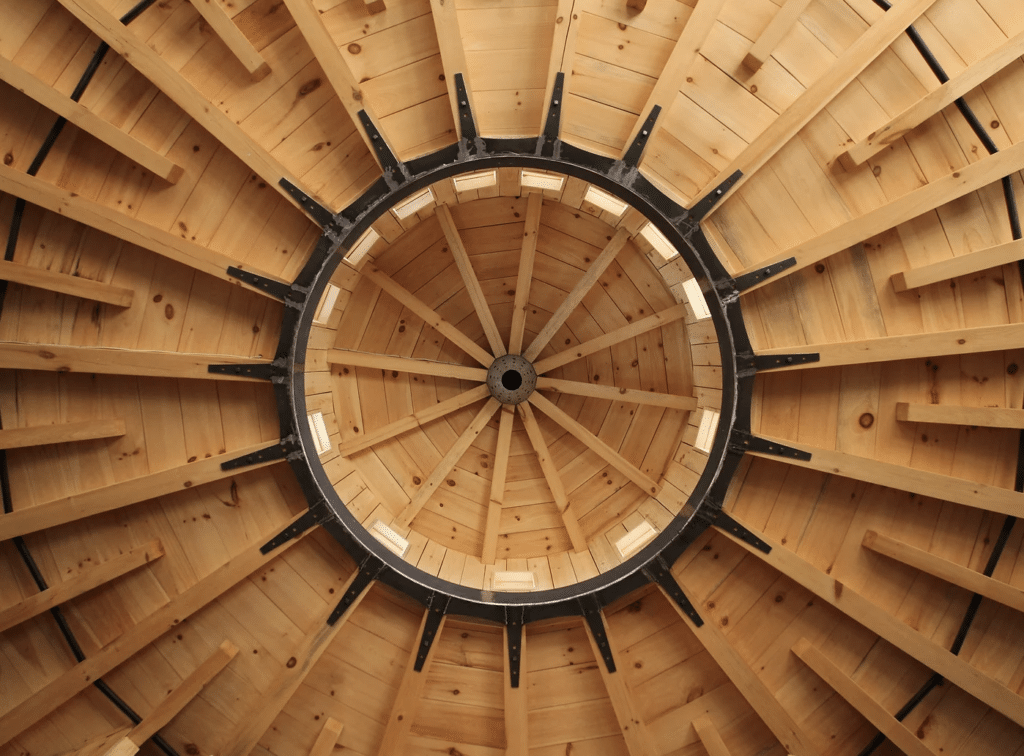

Buildings are far more than the sum of their parts. The task is to imbue them with the unique personality of all those who make it. We believe it becomes a living thing whose life affirming qualities are contagious.

Sacrifice

Beginning a building is seen as a force unleashed and something submitted to, regardless of the toll it takes.

Commitment

Architecture and building is neither solely a business or profession, but a way of living and being in service to others.

Objectification

“How do you price this?…we don’t.” The fact that we can make a building that defies common business logic and conventional understanding and still persist is an affirmation of the building’s intrinsic qualities and the redemptive nature of the work.

Mystery

A persistent recurring feeling when visiting an old project is to feel its separateness, that it is a thing in itself, the quality of the ‘totally other.’

Communitas

Operate with little formal structure, hierarchy, specialization or employees. We use little to no subcontractors and the labor mix ebbs and flows, composed of the core team, old colleagues, new homeowners, interns, volunteers and friends – whoever can pitch a hand. We teach anyone how to make. We often form life-long relationships with our clients and crew. Making dwellings brings structure and meaning to life.

Ecstasy and Flow

Common in craftwork and ever present in the timeless way of building (Alexander, 1979). Recognition that processes must create space for ecstasy/flow to occur otherwise the work is oppressive and therefore profane.

How and why these ways of working emerged over time to create social conditions for resilience and solidarity is the subject of the presentation. The conclusions drawn suggest that the ‘properties of the sacred’ are often themselves quotidian in nature, innate to everyday life if allowed to flourish and play an important role in social life.

This presentation is preceded by a survey of the conference attendees asking them to identify which ‘properties of the sacred’ are present in their practice. The results will be presented at the end of the presentation. The survey contains an abridged description of the properties for reference which will hopefully provide for informed discussion.

References

Belk, R. W., Wallendorf, M. , and Sherry. J. F. (1989). “The Sacred and the Profane in Consumer Behavior: Theodicy on the Odyssey.” Journal of Consumer Research 16(1), 1–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2489299.

Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. United Kingdom: Harcourt, Brace, 1959.

Durkheim, Émile. The elementary forms of religious life. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Katsiaficas, George N.. The subversion of politics : European autonomous social movements and the decolonization of everyday life. United Kingdom: AK Press, 2006.

Alexander, Christopher. The Timeless Way of Building. Taiwan: Oxford University Press, 1979.