Linda Berry ljbaiawcc@gmail.com

Hawaiian Belief System

Those of us with a Christian background have ancestors who were created in paradise, but were soon thrown out.

Hawaiian cosmology offers the opposite. God created the sky father, the earth mother, an older brother in the form of a taro plant (an essential to the Hawaiian diet), and finally, the younger brother, man. Thus man is linked in a loving family relationship to the plants and animals of his environment, to the stars and planets in the sky, and to the land itself. Man regards the āina, the land, as part of his family, with compassion and gratitude. This attitude is still held by contemporary Hawaiians:

I have two convictions in life. One of these convictions is that I am Hawaiian. The other conviction is that I am this land, and this land is me. [1]

Hawaiian well-being is tied first and foremost to a strong sense of cultural identity that links people to their homeland. At the core of this profound connection is the deep and enduring sentiment of aloha āina, or love for the land. Aloha āina represents our most basic and fundamental expression of the Hawaiian experience. The āina sustains our identity, continuity, and well-being as a people. It embodies the tangible and intangible values of our culture that have developed and evolved over generations of experiences of our ancestors. [2]

Mana is the life energy, the living spirit, that flows through all living things, including land and man. Hawaiians access this living spirit through the six senses: the five senses that we ordinarily recognize, and the sixth sense, the na’au, or belly center.

Manifestations of the Hawaiian Belief System

These beliefs manifest in a holistic view of the environment, a concept of land commonly owned, and everyday access to spirit.

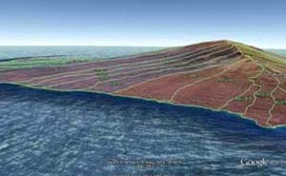

Traditional Hawaiian chiefs developed a sophisticated system of ordering the land to make society more productive, based on Hawaiians’ loving relationship to the land. Each island was divided into roughly pie-shaped areas, starting at the top of the mountain and continuing down into the surrounding ocean. Each section or ahupua’a contained a variety of cooler upland forest and warmer lowland climates, waterways, freshwater wetlands and marine areas, providing the people of each ahupua’a with everything they needed to survive. Gulches carried rainwater from the forested uplands down through the taro fields and into fresh-water fish ponds. The Hawaiians cherished and protected the relationships between the different parts of the system.

[3] Ahupua’a boundaries on Maui

The brilliance of this system reveals itself in the numbers of people it supported. At the time of first contact with outsiders in 1778, the entire population of the Hawaiian Islands was entirely selfsufficient. Now the islands import 92% of their food. Only 8% is produced or gathered locally. With the exception of Oahu, each island then, under the traditional ahupua’a system, supported more inhabitants than live on each island now.

While the chiefs and common people held all the land in joint tenure, one’s work on the land gave each inhabitant the right to live in a specific place. This differs from the American concept of squatters’ rights, which grants land ownership to one who lives on and works a specific plot. And it differs from the idea of land ownership based on a paper deed rather than on the actual deeds of a lifetime.

Accessing the mana, the spirit of the land is an everyday occurrence. For example, when a new project comes up for review by our local Design Review Committee, a Hawaiian member reminds us to go walk the site, not with camera or tape measure, but with our six senses attuned to what the site can tell us. In attending to our senses, we are brought into the present, where spirit can reach us, allowing mana to manifest.

This architect and the āina

I had learned about the ahupua’a system of land division at a state planning conference, and, while I intellectually understood its significance, I came to appreciate it differently while hiking up Kulanihakoi Gulch. The gulch, subject to frequent flooding, was similar to one responsible for destroying in 1910 an historic stone church near my home. At the highway, the bridges reveal the gulches as dry, shallow, unimpressive depressions. They look innocuous when we routinely drive by, so I was curious to learn how one had the power to destroy a massive building.

Before beginning the hike, we called a kahuna who confirmed that it had been raining heavily for over an hour, making a flood in the gulch likely. We agreed to begin hiking in the gulch itself to get past the highway, then climb to the adjacent ground as soon as practicable.

At the point where we climbed out of the gulch, we paused and formed a circle to do a blessing. As we raised our heads from the blessing, we heard a sound like a distant waterfall. As the sound increased, a finger of water came around the bend, followed by a shallow river. As we watched, the water climbed higher and higher on the rocks in the gulch, until it reached four or five feet in depth and filled the width of the gulch. Seeing the water flowing into the dry gulch aroused in me the same feeling of understanding and of being understood that I had felt on entering the Pantheon and at Salk Institute, like a doorway had opened for me.

Water-filled gulch

We continued to hike along the top of the gulch, while the water flowed below us. At one point the canyon reached over 100 feet deep, with steep rocky sides, indicating the volumes of water required to erode such a canyon.

Seeing that water flow downhill brought the gulch to life for me, and with that, brought the land to life for me as well. All of a sudden I knew my connection to the āina. Interesting to me is that, unlike the flash of insight and connection which I had experienced previously in some buildings, this sense of connection and understanding is ongoing because the land is always here, providing a continual feeling of being held.

Application to contemporary architecture

In 2009, I was invited to design a Denver airport-type canopy to cover the outdoor areas of Maui Mall, to make it more competitive with a covered mall nearby.

During the design process, in walking the site, I realized that the delightful contrast of sun and shade, the caress of the trade-winds and the fragrance of flowering trees would all be lost under a canopy. I noted there were three distinct paths, all leading to a center point, where a ring of palms surrounded a circle of concrete. Every time I walked into that center, I felt like I had reached the heart of the mall, but it was lifeless.

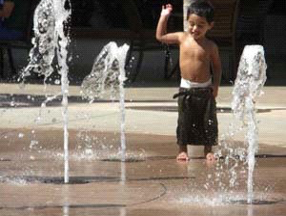

I shared my experiences with the owners and recommended that instead of enclosing the space with a canopy, we build within that empty circle, a fountain where children could play, with shaded seating for their parents. The moving water of the fountain and the children playing in it would bring life to the mall.

The owners agreed, and at the end of construction, we held a traditional Hawaiian blessing. The kahuna said, “We on Maui know that water is a blessing. This fountain is a sacred gift to the community because each time our children run through this fountain, they will be blessed.”

Two years later, a native woman who writes a weekly newspaper column mentioned that she had enjoyed taking her grandchildren, visiting from the mainland, to do all the traditional Maui activities and included in her list, “playing in the fountain at the Maui Mall.” Consider this question: how did a two-year old fountain become “traditional” on an island where tradition is taken seriously?

Why share the Hawaiian mode

A repeating issue inspired this paper. In the past year, our local Design Review Committee reviewed three projects involving gulches. Each of the architects proposed constraining the gulches which run through their sites by enclosing the gulches in concrete culverts and building over them.

The areas of these projects are subject to flooding, causing silty runoff into the ocean, damaging marine habitat. Converting natural gulches into concrete culverts will exacerbate this. In spite of encouragement to do otherwise, the architects will not rethink their plans. Ironically, these architects each claimed they were creating a sense of place within their projects, oblivious that they were in fact burying the actual sense of place, the existing living spirit of the land, the mana.

Conclusion

My wish is that, as architects, we learn to view the land as a whole system, not isolated sites, and that we detect with all our senses the powerful sense of place within a site and allow that mana to express itself in our designs. Then our built designs will rise up from the land, embodying within their forms the spirit of the land.

References

Beamer, Kamanamaikalani, No Mākou Ka Mana, Liberating the Nation, Honolulu: Kamehameha Publishing, 2014.

Ho’omanawanui, Ku’ualoha, “Hanohano Wailuanuiaho’āno: Remembering, Recovering and Writing Place,” Hūlili, Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Wellbeing (Volume 8, 2012) 187 – 244.

Kanahele, Pualani, “I Am this Land and This Land Is Me,” Hūlili, Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Wellbeing (Volume 2, 2005) 21 – 30.

Kikiloi, Kekuewa, “Rebirth of an Archipelago, Sustaining a Hawaiian Cultural Identity for People and Homeland,” Hūlili, Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Wellbeing (Volume 6, 2010) 73 – 116.

Lindsay, Elizabeth Kapu’uwailani, “The Hour of Remembering,” Hūlili, Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Wellbeing (Volume 3, 2006) 9 – 18.

McGregor, Davianna Pōmaika’i, Nā Kua’āina: Living Hawaiian Culture, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2007.

Oliveira, Katrina Ann Kapā’anaokalāokeola Nākoa, Ancestral Places, Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press, 2014..

Steinbeck, John, America and Americans, New York: Viking Press, 1966

Whittaker, Elvi, The Mainland Haole: The White Experience in Hawaii, New York, 1986.

Young, Kanula G. Terry, “Thru One Lens: Sources of Spiritual Influence at Kamakakūo Kalani,” Hūlili, Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Wellbeing (Volume 2, 2005) 21 – 30.

[1] Kanahele, Pualani, “I Am this Land and This Land Is Me,” Hūlili, Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Wellbeing (Volume 2, 2005): 23.

[2] Kikiloi, Kekuewa, “Rebirth of an Archipelago, Sustaining a Hawaiian Cultural Identity for People and Homeland,” Hūlili, Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Wellbeing (Volume 6, 2010): 75.

[3] Google Earth with overlay from Aha Moku website, “Maps of the Islands”, http://www.ahamoku.org/index.php/maps/#map.