Erling Hope

Society for the Arts, Religion and Contemporary Culture, NYC hopelitwrk@aol.com

www.sarcc.org

Recent decades have seen an abundance of inspired innovation in the design and arrangement of worship spaces. But this success is at odds with the stubborn difficulty the visual arts continue to have in working out a productive relationship with these spaces. The radical and profound insights which the past century’s artistic explorations have yielded rarely find any comfortable fit as focal elements for worshipping communities in the United States. With notable exceptions, and many partial exceptions, the invitations of truly bold artists to design, appoint, and embellish these spaces yields far more bitter fruit than the efforts of the truly bold architects to house them. Communities are torn by bitter disputes about the suitability of the labors of the artist for the mood and actions of the sanctuary, and the cliché of the artist alienated by the conventions of the faith community is reinforced, to no one’s benefit. At the same time, fervent worship is cheapened by the empty witness of artwork anchored in its own clichés.

The problems lie in part with divergent approaches to a fundamental and recurring question of our times; that of the relationship between the individual and the community. Visual artists have inherited a conventional ethos which vigorously interrogates any subservience of individual to community, whereas nearly every Jewish and Christian tradition affirms the individual’s responsibilities to the faith community, to varying degrees. And these Abrahamic traditions are by no means unusual in this among the wider family of faiths.

That is the broad view. In a narrower view, the process by which artist and community conventionally interact is also at fault, and is far more, in a sense, fixable. I propose to address, in a partial way, two concerns raised by these conditions. Call them the “Why” and the “How.” Why artists working within contemporary modes of expression should be participating in the formation and embellishment of these spaces–what they have to offer which cannot be satisfied by the acknowledgedly rich relationship being forged with contemporary architecture–and how these artists and these communities might come together and weave, as warp and weft, the fabric of a new and productive relationship between artist and church or synagogue. This would be a relationship informed by respect, each for the commitments of the other, and each for the gifts of the other.

—————

A myriad of theoretical and theological reasons argue for the inclusion of visual artists in the design and appointment of the sanctuary space. But a host of practical reasons pertain as well. Contemporary visual artists are technicians of a family of concerns which can support and enhance even the most institutional of religious traditions. Among these concerns are the obvious ones, such as engaging the whole human being-–emotional and sensual as well as intellectual, social, intuitive—through appeal to the senses; providing an enlivening and stimulating environment, demonstrating care and attention to liturgical actions by adornment of the furnishings and objects which serve them, etc.. What may be less obvious, but no less important,

is that several of the core impulses of the last century of artistic innovation are in deep conversation with some of the fundamental values of—not just religion generally—but of Abrahamic tradition specifically. The aestheticization of the ordinary, of the marginal, even of the monsterous, represents a kind of orchestration of awe. This awe is what enables the artist to see the ordinary or the outcast as if for the first time, and this seeing as if for the first time is an expression of metanoia. It represents, as it were, the redemption of the world. And while this set of values falls most closely into alignment with Christian tenets, it’s roots are firmly set in the socalled priestly impulse of Abrahamic tradition more widely, which seeks to restore worshippers into proper relationship with the cosmos.

If the arts have inherited this priestly impulse from Judeo-Christian roots, they have inherited the strong influences of its prophetic instinct as well. If the priestly is the remedial function (by this usage), the prophetic serves as the diagnostic. The confrontational stance which characterizes much of this art, and bars it from inclusion in the space called sanctuary, is not ultimately necessary for the mission of revitalizing culture and tradition by shining a light on its blindspots. Artists can and do interrogate the role of language and of sexuality in human experience without producing blatantly sexual or bafflingly nonsensical images. Artists do explore the religious dimensions of the act of questioning… tacitly. They express the metaphysical weight of irony … without nihilistic sarcasm. It happens. Not all the time, of course—subtlety is a rare thing, and there is plenty of crap out there in every discipline—but often enough that the visual arts remain relevant to the project of corporate worship. More importantly—and this is as extreme a claim as I will make—if current organized religious traditions harbor any long-term plans to remain relevant, unsupported by the poisonous suspicion of critical thinking, of irony, of questioning, of sexuality, of the prophetic impulse which seeks to enliven it, they will need to learn to engage these issues productively. Artists offer the best chance for them to do so.

So that’s why. Or, these are some reasons to keep at this thing. As for how; that may be a more delicate question to address. It is perhaps interesting to note that, within the creatively tumultuous productivity of the last couple of decades, two of the most arresting examples of (broadly defined) “sacred space” have emerged under the care of what is probably the least liturgical sect in the world. Quakers, or Friends—the Religious Society of Friends (the tradition from which I come)— spawned, with Minimalist artist James Turrell, the Live Oak Meeting House in Houston, Texas in 2001. His signature treatment of the skylight at the center of the structure invites, orchestrates-engineers, really—a state of altered consciousness. He engineers a state of altered consciousness. Using the simple technique of feathering the border of the skylight to a sufficiently fine edge that no actual edge is perceptible, he denies the human eye an edge or detail to fix on and register distance. The infinite depth of the sky’s falling away is rendered as though a flat panel suspended from the ceiling, forcing the viewer into a new cognitive posture of observing oneself observing. And this awareness is one of the trim tabs of religious or spiritual experience.

The other example to take from the Quaker efforts would be the “Eyes Wide Open” public, temporary memorial to those killed in the Iraq war. Here, an empty pair of combat boots represented each American service person killed in the first years of that war, and varying numbers of regular “civilian” shoes represented the unknowable numbers of civilians dying violently. The effectiveness of the use of the boots is difficult to convey. Each boot had a name tag tied to it, with, for the service people whose families consented, the name, rank and age listed (the boots were not those of the actual combatants). For those few whose families did not consent, the tags were labeled with “anonymous.” Similar details accompanied the civilian shoes. It was not uncommon for nausea or trembling, or other bodily emotional responses, to accompany reflective visits with the ghostly absence of these legion of lost compatriots.

Here is what is interesting to me about these two examples: Though their functions are very different—they could be said to embody the finest expressions of priestly and prophetic impulse in the arrangement of “sacred space”—Turrell seeks to restore us to a right relationship with creation; Eyes Wide Open forces an emotional confrontation with the fruits of our (collective) action. Also, one is permanent and the other temporary; one looks up and one looks down and this itself is a profoundly important distinction. Nevertheless their degree of effectiveness is roughly comparable. Using simple means they reach far beyond themselves, these modest arrangements of matter. And they reach us deeply and uncannily.

But the first one, Turrell’s Live Oaks Meeting House, operates under the conventional model for the interaction between artist and faith community. The artist-hero, alone on the desert mount of monastic studio practice, appeases, beguiles or wrestles revelation from the muse, and returns with it to the city gates, for the people within to accept or reject it.

It is a particular blend of Moses, Jacob and Ezekial, and it works wonderfully for the gallery system. It does not work for the worship space of the 21st Century, as it did not work for the worship space of the 20th Century. The audience for the gallery self-selects; the artist can deploy the disregard for community and society necessary to plumb the depths of existential authenticity, and wager that a discriminating clientele will find them. But the worshipping community is preformed. The artist cannot waltz in, foist the fruits of creative exploration on this gathered community and expect universal acceptance.

The sad truth, or one sad truth, about the Live Oak Meeting House that we are unlikely to read about is the discord it wrought on the Quaker community there. Anecdotally, we hear of schisms in that congregation. We hear of attrition as members who found the presence of the artist too prominent in the mood and effect of the building, leave the community to worship more comfortably elsewhere, or perhaps to not worship at all.

Yes, we also hear of new members joining the community partly because of the adventurous spirit attested to in the witness of this built environment. And some aspects of these adjustments will ring familiar to architects involved in the design of these buildings. But architecture never lost, and can never lose, its connection to collaborative process. In any case, we cannot ethically engage in these projects with the assumption that the community will be rearranged by them. The visual arts have undergone such a radical reworking of their social contract in the last century that the impact on these types of projects almost guarantees some amount of rearranging.

So the delicate question of how to bring artists into this process is central. We cannot count on any current system of commissioning such works to generate enough agreement on what will work best for a space. The best artists around today have their passionate, articulate detractors. The tradition itself is built to subvert consensus. If an artist or a work of art is true to the risktaking heritage of its tradition, how do we structure the relationship so that an already formed community can be reasonably assured that the relationship will be fruitful?

Short answer: The community must be brought into the creative process. Members of the community must feel a sense of participation in, and ownership of, the creative process.

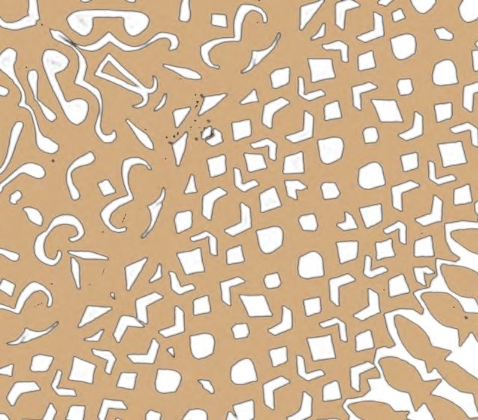

I have been working on several approaches to working with faith communities to collaboratively generate patterns which can be transposed into design elements within a worship space. These approaches make the design and appointment of a worship space a truly collaborative product of the community it serves, and an opportunity for the community to learn about itself as individuals and as a group. At the same time, it affords the artist room to explore creative possibilities without absorbing all the risk of speculative creative effort aimed at skeptical and unfamiliar audiences. The community provides the raw materials, and the professional artist or designer stewards the creative energies of the community to form a cohesive and durable vision. Starting with simple processes–pen and ink, scissors and paper–with conversation, and with strategies for creating a workshop environment that fosters reflection and expression and activates the ontological imagination, artist and congregation move on to use simple digital design applications to turn the products of the gathered community into figurative and abstract patterns.

But patterns themselves, if poorly applied or casually considered, can undermine the entire enterprise, suggesting the superficiality of a graphic surface, or the busy-ness that banishes silence. The promise of religious belief and practice is that it should provide us a glimpse of the larger pattern of the cosmos. Glimpsing the whole in the fragmentary; this is the hunger behind the impulse. Graphic patterns, executed under the inspired guidance of professional artists and deployed selectively, can serve to represent this function viscerally, engaging the whole human in the worship act. Pattern can organize space, provide texture and visual interest, and suggest order, expansiveness, and playfulness. Arranging fragments of radial patterns, for example, in elements of the interior architectural design or furnishings, so that the center of the glimpsed pattern corresponds with altar cross or aron, focuses attention and asserts ontological claims native to their worship spaces. They can be used as ornamental motifs on furnishings, banners and appointments, or as more focal elements of murals, altar screens or leaded glass panels.

The ways a congregation goes about “doing” liturgical art are evolving. The iconic model of the commissioned artist, adrift in the existential ocean of solitary studio practice, is giving way to more collaborative approaches. But collaboration without some sort of informed guidance will have difficulty crafting a clear vision. The methods I am proposing and developing suggest new ways to enact this collaborative approach, while generating genuinely useful and provocative design elements for the contemporary worship environment.

————–

One of the models for this approach is the Judeo-Christian hymn tradition. It is impossible to overestimate its genius. Each human body pushes its voice out into the space with singular effort; each voice rises and arcs into the envelope of the joined refrain, disappearing into the gathered whole. These are moments when ordinary grace reaches into extraordinary Grace. It perfectly describes to our senses our faithful role in the universe.

When we hear our voices leaning in to a larger song of a community, we know that we are members of that community, if only as sojourners. When members of a faithful community see ourselves reflected in a work of art or design, can identify our own marks in the larger canvas, we know we are spiritually at home. The thrill of participation in the corporate, communal creative effort is an experience of ordinary, extraordinary Grace. It is material hymnody.