Phillip Tabb

Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas (USA)

cassicat7@yahoo.com / ptabb@archone.tamu.edu

Louis I. Kahn [1]; Phillip Tabb in Montepulciano, Italy

TOPIC SCOPE

Drawing is a form of visual art that can be a representational, impressionistic, abstract, informational, or even imaginal, yet it can be part of a transformative experience as well. Drawing can be a process of deepening and of extraordinary discovery. It has the power to enable one to be awake in a place and to really see what is there, contributing to insights and an eventually enlivened presence. Mythological explorations can be renewing when found in drawing as they become what author J. R. R. Tolkien called “mythopoeia,” and a visual narrative of archetypal themes emerging where the myth-making is closely connected to the actual experience of a place [2]. Myths are said to take place before a space becomes a place and this process becomes a sacred narrative, which is attached and gives significance to it. Theologian Belden Lane, in his Axiom for Sacred Place, suggests that a place may be tread upon without being entered [3]. This suggests that the sacred realm may exit, but may not necessarily be readily accessed or initially revealed. To call into being the sacred or mythic realms of a place, seems to require either a quieting process into the ethos of the place, enactment with ritual, or possibly a conscious awakening through a process like drawing. It is this phenomenon, which is the focus of this extended abstract. And to that end, four place-oriented drawing typologies are explored: quick insitu sketches, extended field drawings, studio enhanced drawings, and mythological landscapes.

QUICK IN-SITU SKETCHES

In-istu drawing is an on-site drawing method where fast sketching techniques are combined with the heuristic of a general perceptual awareness of a place. On one level it provides the opportunity for immediate immersion, particularly when traveling through interesting places. On another level it beckons for a gestural feeling for a place and an essential rapid representational response, converting impulse into image. Most importantly, in-situ sketching requires the development of a quick “field” drawing style (squinting, scanning, quickly composing, and then drawing) where the entire composition can be captured in one impulsive setting. Often the sketch uses simple lines or tones capturing the entire scene and then focusing in on some characteristic details to give it meaning and place-boundedness. As the drawing nears completion, there often is a euphoric feeling with the understanding of the place or subject the sketch seems to seize.

There is something extremely satisfying and essential with these quick sketches.

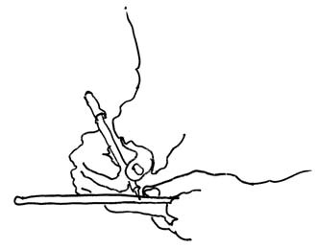

Plate 1. In-Situ Place Sketch – Duomo

The sketch illustrated in Plate 1 was drawn with very simple and quick line work within five minutes at the Piazzale Michelangelo overlooking Florence. There was a touch of color added to the Florence Duomo sketch to further emphasize its function as a place marker. The presentation will show the Galata Tower Sketches, drawn from across the Golden Horn and other examples of this drawing typology.

EXTENDED FIELD DRAWING

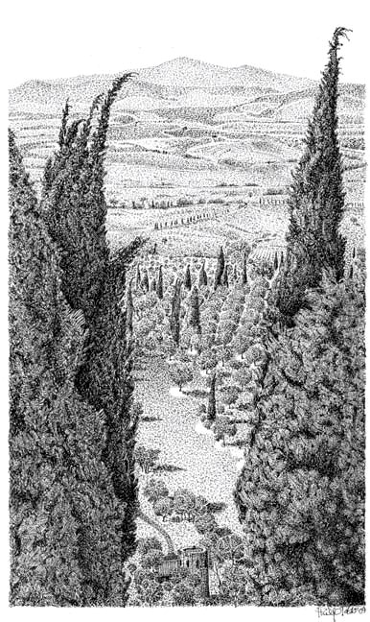

Plate 2. Extended Field Drawing – Amiata

STUDIO ENHANCED DRAWING

Extended field drawings, as compared to in-situ place sketches, allows for a more contemplative immersion experience simply because more time is given to the process. And, of course, this time allows for greater emplacement and access to insightful moments. This added time seems to be split between being quiet and simply looking, seeing and being in the place, and being fully engaged in a more detailed drawing process. There is a deepening into the fabric and detail of the place as it begins to reveal greater levels of the outward manifestation of its living inner spirit. And the drawing technique reflects this awareness. According to author Julia Cameron, there is an “in-dwelling” creative force that can be accessed and it forms a mystical union between the self (artist) and the spirit of place (divine) [4]. The presentation will focus on three drawings that were initially drawn at each of their respective sites. The San Gimignano Tower was totally drawn in place over the period of forty-five minutes. The drawing of Monte Amiata was initially drawn from one of the terraces in Pienza (Plate 2), and later enhanced in studio. And the drawing of La Consolazione located in the Val di Chio was entirely drawn over a period of several hours from the comfort of my window in my apartment at Santa Chiara, Italy.

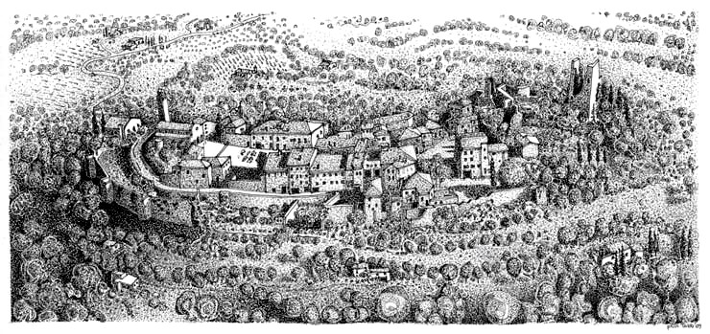

Studio enhanced drawing begins with being present with a site, making initial sketches and taking subject photographs. Then the drawing is worked in the studio environment where it can either be re-constructed or enhanced and developed into a more precise drawing. This process can be augmented with more controlled rituals, meditation, with focused and intense drawing episodes. Dutch artist and author, Fredrick Franck suggests that “time stands still” and there is the potential for rediscovering the world [5]. This drawing technique seems to support this process where multiple drawing episodes allow for meditation, visual research, reflective adjustments, and careful drawing practices. The presentation will illustrate drawings in this mode as shown in Plate 3 and will show the greater detail and rendering care afforded by more time and controlled studio conditions. Usually these drawings are more abstract, more detailed or difficult to revisit, as in the case of Civitella in Val di Chiana, photographed from an airplane. The drawing, Chiesa Collegiate, was initially sketched in pencil on site and later enhanced and rendered in studio.

Plate 3. Studio Enhanced – Civitella in Val di Chiana

MYTHIC LANDSCAPES

According to Robert Samples, a symbolic metaphor exists whenever a symbol, either visual or abstract, is substituted for an object, process or condition [6]. In a landscape then, the metaphor can be a generative element of that landscape and may be seen as a guiding evolutionary force. Mythic landscapes are a drawing process, where the mythic realms coexist with the natural or human-made elements of the place. The presentation will illustrate the Chinese White Tiger with the celestial constellations of the west. Pegasus is one of the first accounts of the notion of “spirit of place” where his hoof touching the ground creates a healing place and the point where the divine interacts with the Earth (Plate 4) [7]. And the Winged Lion of Venice is related to St. Mark and his protective and healing qualities of place. Myths of creation, place myths, concepts of wholeness, division of the universe, the conjugation opposites, heroic tales, animal myths, and emplacement drawings are all explorations that are hopefully intended to enrich and expand a sense of beauty and wonder that still remains in the places we live and visit [8]. The mythological dimension can describe the deep structure, subconscious and sacred nature of the place. Drawing in this context is a way of remembering (re-membering).

An early notion of Genius Loci comes from the Greek mythology of Pegasus the winged horse-god. The divine (hoof) connects with the earth (ground) and spirit is transmuted to the physical and place that defines it. The word for Pegasus has been related to “springing well.” In the sketch the constellation for Pegasus and the cosmos open a way to earth and the spirit of place.

Plate 4. Mythic Landscape – Pegasus [9]

SUMMARY

Traditional forms of sacred art, such as Tangka Painting, Icon Writing, Mandala Sand Painting, Zen drawing, Vastusutra Upanisad, Persian Miniature Painting, and Islamic Patterning, each seem to grow from the discipline of a slowing down process of the mind, reduced temporal density, an opening to divinity, and an anchoring into an observational presence. There are many sacred drawing practices, however, this presentation will explore and illustrate the four-place drawing typologies previously discussed. The quick in-situ sketches and drawing vocabulary develop hand-eye coordination and the ability to capture a scene or place loosely (generalizing cognition). Field drawing gives the opportunity for site-specific emersion and the time to deepen into the place (sensual experience). Studio-enhanced drawings create a context for focused attention, and ritualized drawing development (differentiating cognition). And mythic landscapes allow for the imaginal world of myth and magic to be revealed (mythopoeia). Parallel engagements of these drawing techniques help with informing interactivity and an enriched sacred practice – developed drawing skills aid in clarity representations and sacred practice brings emotion and spirit into the process. It is the accumulative combination and interaction of these techniques that contribute to seeing, drawing and developing a place-oriented sacred work of art. And of course, it is the experience that emerges out of this process, which is most intriguing and important.

I see and where the eye is opened, all is illuminated. – The Tibetan [10]

REFERENCES

- Richard Saul Wurman, What Will Be Has Always Been: The Words of Louis I. Kahn, Rizzoli, New York, 1986.

- J.R.R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf: Including “Mythopoeia,” Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 2001.

- Belden Lane, Landscapes of the Sacred: Geography and Narrative in American Spirituality, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2001.

- Julia Cameron, The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity, Tarcher Putnam Books, New York, 1992.

- Fredrick Franck, Zen as Seeing: Seeing/Drawing as Meditation, Vintage Books, 1973.

- Robert Samples, The Metaphoric Mind: A Celebration of Creative Consciousness, Addison Wesley Publishers, Boston, 1978.

- Gail Thomas, Pegasus, Dallas Institute for Humanities and Culture, Dallas, 1993.

- Michael Brill, Using Place-Creation Myths to Develop Design Guidelines for Sacred Space, NIA Grant Publication, 1985.

- All work illustrated in plates 1-4 of this abstract were done by the author using 005 Micron pens on watercolor blocks.

Alice A. Bailey, The Labours of Hercules, Lucis Publishing, London, 1974.