David H. Pereyra

University of St. Michael’s College in the University of Toronto, Ontario (Canada)

david.pereyra@utoronto.ca

Beauty as a transcendental quality of being invites one to enter the world of contemplation. In his book The Relevance of Beautiful and Other Essays, Hans-Georg Gadamer argues, “The experience of the beautiful in art is a form of knowing.”i To prove this argument, he works with three basic concepts, Play, Symbol, and Festival. I will argue that by designing a church with these concepts in mind, we can help a congregation to have a true experience of transcendental beauty. First, I will apply Gadamer’s three concepts to the art of liturgical celebration illustrating them through the spaces of three Christian communities, and then consider their potential effects.

According to Gadamer, these three concepts are built upon each other: the three relevant aspects of play—freedom, excess, and purposeless—under some rules are sending an invitation to participate in a different communicative dimension. The invitation is presented in a symbolic language within the framework of festival.

The experience of play is described by Gadamer as an activity without purpose. If there are actions without worldly purpose those are worship actions, and the space to enact them should be a recreation of an entire spiritual world where the soul can rest from purpose activity.ii The Reconciliation chapel at the Taizé community in France gives this sense, a place where any level of anxiety is removed from worshipers. Play requires rules, like liturgy that gives many directions about language, gestures, colours, garments and instruments; a good liturgical design must honour all these rules.iii Our deepest experience of play is when we play along with someone else.iv Worship spaces must allow a full participation of the assembly in all its expressions. Rows of pews were appropriate for the Tridentine Mass where the participation of the assembly was not a concern, but today unfixed seating makes possible different settings. The Domus Galilaeae chapel of the Neo-Catechumenal community in Israel arranges its chairs around the altar enhancing the idea of banquet.

When it is time to play, Gadamer says, all living beings express themselves more or less which a degree of excess. When it is time to celebrate, congregations should not spare any resources in order to worship God. A good example of this is the Episcopalian community of St Gregory of Nyssa in California. The rich liturgy has components of different traditional liturgies and also the space: the altar table stands in an open space before the entry doors, icons of dancing saints circle overhead, and candles and crosses occupy a platform to the right, in the middle of the building.

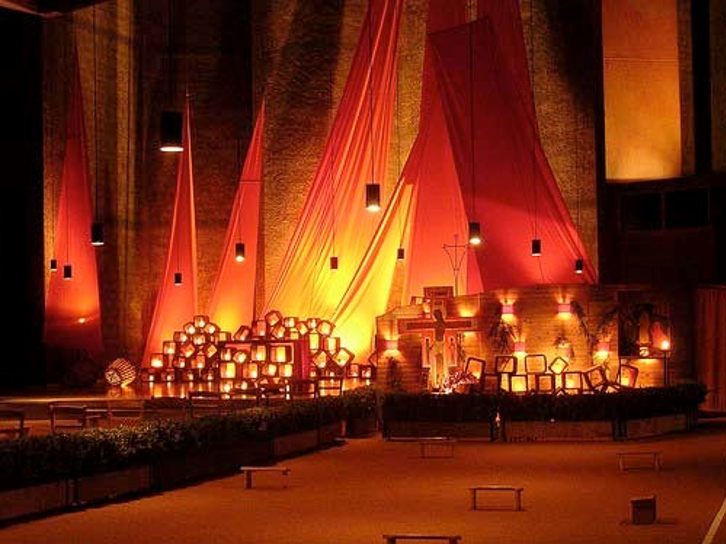

The acknowledgment of symbols is part of the act of play, which constitutes the meaning of the Liturgy in terms of its hermeneutic identity. Liturgical symbols direct our view toward a holy order of things.v Our work is discovering in the liturgy the mystery to imprint them in the character of the liturgical space. This means, in Gadamer’s words, learning how to listen to what liturgy has to say through the space. Places of worship should be a vital expression of the meaning of liturgical play. The Taizé chapel with its apparently chaotic setting, lighting, and textures becomes a symbol in itself of the Mystery.

When Christian communities worship with all their hearths and soul, the celebration becomes a real Festival.vi Gadamer says that celebrating is an art that we have lost, and I strongly believe that we have lost as well the art of designing spaces for the celebration of the Christian liturgy.vii For Gadamer this art consists first in not allowing separation between one person and another.viii This is the aspect ofInclusion, which can be translated into designing a church as a welcoming space. St Gregory of Nyssa is a good example of this aspect. Christians gather in the name of God to enact liturgically a “festival address”, sometimes requiring a profound silence from the ones who are listening.ix A good liturgical environment is the Reconciliation chapel, inviting worshipers to contemplate and participate in a sacred silence environment.

The last aspect is time. Gadamer says, “The temporal structure of the performance is quite different from the time that simply stands at our disposal.”x Liturgy’s temporal structure is quite different from everyday time.xi Liturgy imposes its own time upon us; it invites us to linger in its rituals. Our duty is to discover its autonomous time to imprint on the forms of architecture. “The essence of temporal experience of art is in learning to tarry in this way.”xii Liturgical architecture perhaps is one of the ways to grant us, finite beings, the experience of eternity.

Conclusion

Gadamer has sought an anthropological foundation in the phenomenon of play as the highest expression of freedom. The three mentioned communities, Taizé, Neo-Catechumenal and St. Gregory, worship regardless of age, race and social class, with a deep sense of belonging. Their spaces are a reflection of the unity of Christian of the past and the present.

One of the primary reasons for Gadamer’s work was to make us aware of our relationship with the world and how in our creative efforts we are trying to retain what threatens to disappear.xiii The liturgy through its rites gives to the temporary a new form of permanence. These three sacred spaces retain the ephemeral, connecting the present with eternity, throughout the actions undertaken in their different liturgies, Neo-Catechumenal celebrating an everlasting banquet, Taizé’s community giving the experience of being set apart, Episcopalians inviting to sing, to dance, and to become God’s friends.

The three communities have designed their churches based on the language of their liturgies. The three liturgical spaces are built around strong symbols—Neo-Catechumenal, a big altartable; Taizé, the grand tent in the dessert; St Gregory, a circle of saints dancing above the altar.

Their particular form of play helps them to perceive the eternalness in the temporal and this is because of the symbols.

Finally, the festival: this concept critically challenges our cultural life, where the individual is raised above communal values. Those churches were designed for liturgical celebrations releasing us from our individualistic life.

The experience of the liturgy culminates when one is surprised by the delicacy of the assembly, the priest, the choir and the space itself; they evoke the work, the liturgical celebration, its composition, and its internal coherence to reach, unintentionally, the Eternity present in the moment.

Notes

i – Hans Georg Gadamer, The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

ii – Romano Guardini, The Spirit of the Liturgy (New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 1997),61-72.

iii – A baptism fountain located close to the assembly allows congregation to go there for some ritual actions during some feasts, in favour of “freeimpulse.” A long distance between the altar and the ambo gives a sense of procession of the Book of the Gospel.

iv – Gadamer calls this aspect “participation.” Gadamer, 23.

v – Louis Marie Chauvet, The Sacraments: The Word of God at the Mercy of the Body (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 2001), 11.

vi – Alejandro García-Rivera, The Community of the Beautiful: a Theological Aesthetics (Collegeville, Minn: Liturgical Pr, 1999), 131-135.

vii – Gadamer, 40.

viii – Ibid., 39.

ix – It is the aspect of “speechandquietness.” Ibid., 40.

x – It is the aspect of “temporal structure.” Ibid., 41.

xi – “The ecclesiastical year is a good example, as are all those cases like Christmas, Ester, or whatever, where we do not calculate time abstractly in terms of weeks and months.” Ibid.

xii – Ibid., 45.

xiii – Ibid., 46.