Paul Tesar

North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina (USA)

paul_tesar@ncsu.edu

The proposition I would like to put forth for discussion is that our widely perceived deterioration of a spiritual dimension in contemporary architecture may–among many things–be due to the fact that its vast array of idiosyncratic and constantly changing expressive languages overburdens the human attention economy and thus subverts our ability and desire to penetrate beyond the conspicuous surfaces of buildings: they don’t pass our threshold of relevance, the very entry gate to our sensing, feeling, and thinking being.

“Form is a language, and that language should be intelligible to us: we yearn for intelligibility and therefore for expression. Part of modern anxiety is due to the lack of legitimate expressiveness, because we are surrounded by secretive things that deny us the communion that we think should naturally appear in the work of man in space.” — Eladio Dieste

This statement of concern, voiced by the great Uruguayan architect Eladio Dieste a few years before his death in 2000, proposes an idea that may strike many among us as a peculiar anachronism in today’s aesthetic climate: that architectural expression could have, no, should have a moral dimension, rejecting “secrecy” of expression in favor of one that strives to reach us somewhere on the level of our shared humanity.

This secrecy could result either from a predominantly private and idiosyncratic “language” (if that is not an oxymoron), or perhaps from a muteness that resides at the opposite end of the spectrum, from a neutrality of form that is devoid of content, meaning, or passion. The world of architecture provides us amply with both today, and both have the potential to deprive us of “intelligibility and legitimate expressiveness,” either because we don’t understand what is there or because there is nothing there to be understood.

Dieste seems to be proclaiming something like a basic human right to architectural expression that is “naturally” relevant and engaging, without a need for any “theory” to decipher a secretive code that may inform it. Dieste is not talking here about beauty, or taste, or even appeal– connections to things that are always at least partially subjective–but about something more fundamental: that no expression of architectural form will ever have a chance to affect us, let alone touch us in a spiritual way, if it does not reach us first. This kind of inertia is not a matter of like or dislike, of agreement or disagreement, but an indifference that rises from a sense of disconnection and irrelevance. In the realm of aesthetic experience even feelings of aversion or rejection arise from a form of encounter and are as such a constructive part of the give and take of living. Incomprehension and apathy, on the other hand, point to the exact opposite, to the lack of any “communion.” They are dull, lifeless, and empty. They are the consequence of the fact that something has remained inert and has not passed our all-important threshold of relevance.

Relevance–the condition that an object of experience connects with us and a given matter at hand, that it has the power to affect how we feel, think, or act–is probably the most fundamental screening device of human experience, as it would go beyond our powers to attend to everything that is “there.” We select our environment, usually not consciously, on the basis of relevance to our biological, psychological, and existential condition. In the realm of architecture we are deceiving ourselves if we think that our expressions are addressing submissive audiences, eager to attend to, or even to decipher, what we put in front of them. In the typical case our fellow human beings simply don’t experience architecture “framed”, like a work of art, to which they turn their undivided interpretive attention, but in the course of everyday existence, where the objects of experience are either “naturally” relevant and enter our world–or not.

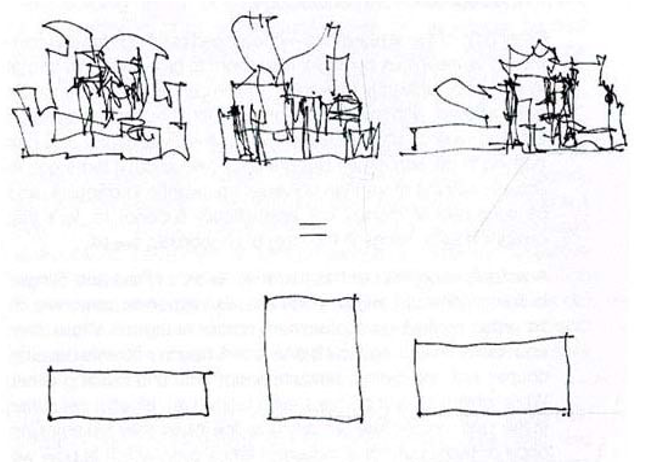

The competition for our attention to works of architecture (among too many other things) has been accelerated in recent times to an almost feverish pitch. It has become an economic necessity for the “serious practitioners” of the art to be unconventional and provocative–in other words disproportionately attention-consuming–as professional success today largely depends on their skill of attracting attention to their work and to themselves through novelty and controversy: conspicuous production for conspicuous consumption. But anytime we experience something new, whose relevance is not naturally given, we tend to exhaust our limited powers of attention–if we attend at all–on the first, the surface layer of experience, to simply figure out what it is we are experiencing and what it might mean. If we experience something with a certain degree of familiarity, on the other hand, as for example with a building in the context of established traditions and types, we can direct our attention to its specific and subtle qualities, to what differentiates this building from other similar buildings we know. In other words, we can use our attention to penetrate deeper into the object of experience, to discover its specific and unique identity, its wonder and mystery, because its general identity is not in question and already known.

This ability to penetrate to deeper layers of the nature of a thing or event seems to be one of the fundamental conditions for our ability to develop a spiritual relationship, as it allows our attention to connect, to reflect, and even to contemplate. Paying attention to this leaf, to this face, to this door–not once, but repeatedly–is not only the initial step of our aesthetic relationship to something, and thus the seed of our impulse for art or the mastery of a craft, but also of a relationship of affection and attachment that can develop and unfold only over time. Things become significant, events turn into rituals, and we discover that we love a place we know.

Attention is one of the most basic gifts we can bestow: a distinction that separates a person, a

thing, or an event from the vast sea of the unattended. This resource is not limitless, and we tend to reserve it for things and people that matter to us and to our existence. Relevance cannot be proclaimed or forced, and without it not much else will happen. This raises of course the difficult question of how things become “naturally” relevant to us, in the case of architecture not just subjectively but inter-subjectively. But that is a complicated matter better left for another day.