Carolyn V. Prorok

Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania

cvprorok@oshun.us

Now it is time that gods emerge

from things by which we dwell….

Ranier Maria Rilke 1925ii

Preamble

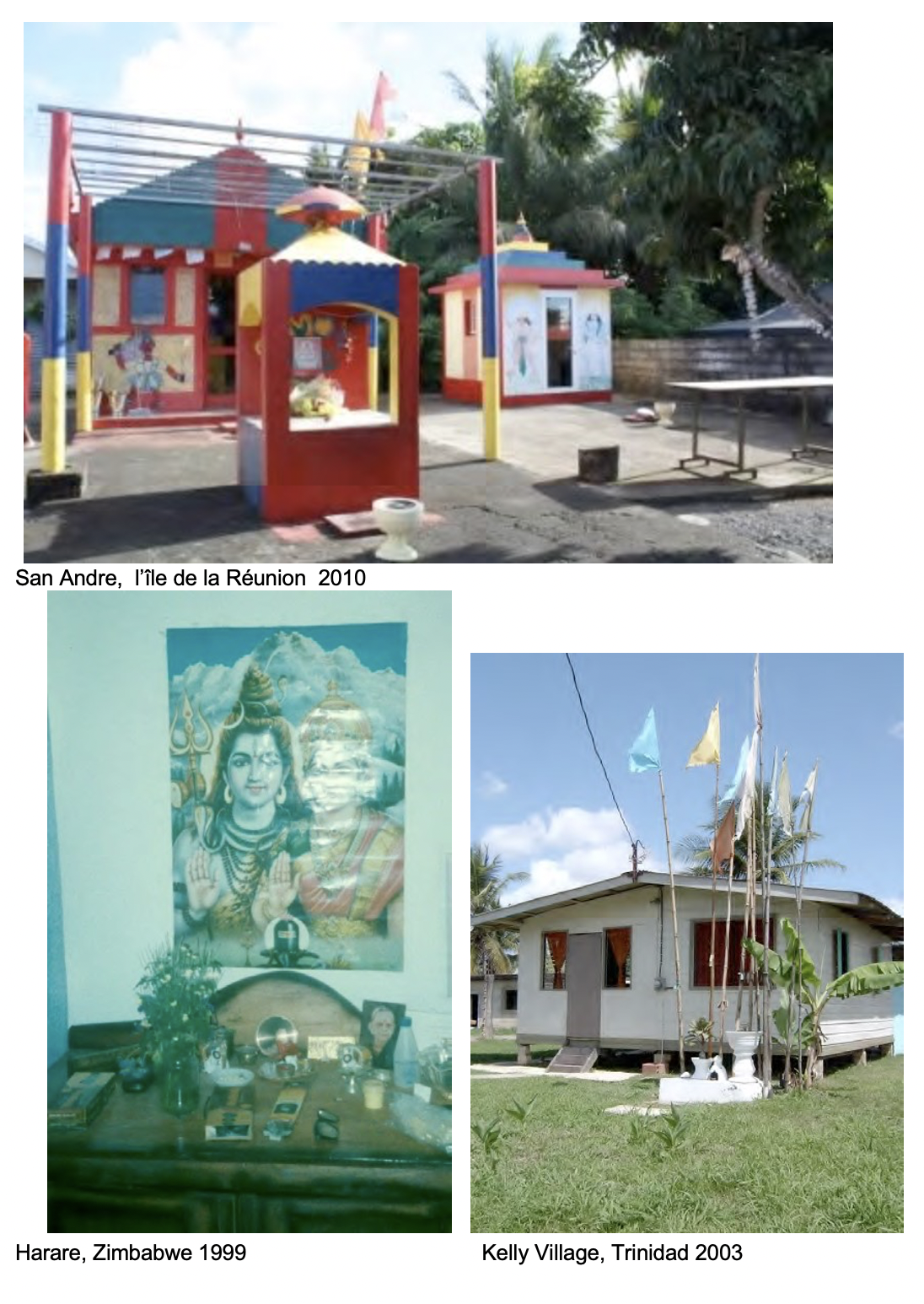

A common perception of Hinduiii sacred space often revolves around magnificent specimens of monumental architecture. Voluptuously sculpted Khajurao, whimsical bas relief of elephants on parade at Mahabalipuram, and the sublime towers of Dakshineswar are among Hinduism’s greatest architectural achievements.iv Mandir, as temples are called among Hindus, may also be somewhat modest in scope and décor. Such temples are found throughout the subcontinent and abroad. Less well-known, yet so numerous as to exist in the millions, are shrines to specific deities in the villages, under trees, along roadways, and capturing open spaces in urban zones from street corners and road dividers to the public side of walled compounds and parks/gardens. They may be small (one square meter to three square meters) but they are often colorful and they attract many passersby who stop to pay respect. Despite countless places for faithful worship in India and abroad, most Hindu families do not visit them often or regularly. Their own homes are centers for ritual observance.

Home Is Where the Gods Livev

Practically invisible to non-Hindus and non-family members are home shrines that are essential for the spiritual and material well-being of households. All practicing Hindus maintain an altar or a shrine in available space inside the home or outside along an interior wall or in a garden. It is here that images and artifacts revolving around the ancestral patriline, the deity that has been worshipped for generations by the patriline, and any other deity with which family members have formed a relationship can be found. Maintaining the shrine, making daily offerings, and reciting relevant prayers every morning and evening are primarily the responsibility of the eldest woman in the home. Men may or may not actively engage with the shrine on a daily basis—but, they do have ritual responsibilities for specific events. This gendered division of ritual labor is rooted in the belief that women, as natural repositories of sakti (the creative energy that makes life in this material world possible), must—through her actions—guarantee the spiritual health (and by extension the material health) of the household. In this way, every Hindu home constitutes a sacred space.

From the 1830s to 1917, Britain (and to a lesser extent France) transported hundreds of thousands of people from the Indian subcontinent to its far-flung tropical empire to labor on plantations and railroads. After WWII, migration to North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and the Arab Gulf States has resulted in a substantial, contemporary diaspora. Combined with the earlier migration, more than 25 million people of Indian origin are living in l dozens of countries. About three quarters of this population identifies as Hindu though this proportion changes with each community abroad. Given the role of the home as the first and primary sacred space for essential life affirming rituals, Hindus around the world have a ready made location for maintaining their faith tradition.

Ante-Architecture in the Hindu Diaspora

Hindus do build public temples, and monumental ones at that, wherever they settle. Local cultural, religious, and political conditions play a role in what Hindus can build and where they can build. If local culture and politics are intolerant of Hindu practices, then Hindus tend to keep a low profile and community events are held in a mundane local structure or at a home that can accommodate the entire community. As conditions liberalize, fully developed monumental structures can be erected. In the meantime, some Hindu communities rely almost exclusively on their home altars for family and community worship—so much so, that private temples begin to mushroom in gardens and alongside houses where the family owns and controls the property. I refer to this process as ante-architecture. It is a dynamic and powerful means of expressing Hindu religiosity without prescribed, designed ritual spaces. Any mundane space—including walk-in closets, pantries, bedrooms, window boxes, garages, and garden sheds—can be converted into a shrine. The home as sacred space is literally defined by active engagement with the shrine. As the family is able to afford it, or life events compel them towards it, an actual temple structure is built as part of the house or alongside the home. Most of the time, this is a vernacular expression that draws upon local materials and remembered decorative styles from the region of origin. Globalized representations of Hinduism and local cultural aesthetics will also play a role. Proper positioning of the deities, associated artifacts, and botanical elements remain fairly constant. Only the wealthiest and most enthusiastic of devotees can hire an architect or specialist from India to design a private temple according to prescribed traditions (e.g., agamas). Instead, each diasporic community—especially those from the 19th century—create their own highly localized, vernacular styles.

Once the deities are installed and the breath of life (prana) is imparted to them through appropriate rituals and daily observance, the home becomes one with the gods. Patrilineal ancestors remain linked to the contemporary family and future generations are guaranteed. All manner of trials and tribulations can be faced with greater confidence. Joyful celebrations are more deeply satisfying when one’s home is also god’s home. In this way, any home space is simultaneously a spiritual dwelling.

All photographs are by the author. ii

The first lines of a poem cited by D.F. Krell in Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings, NY: Harper & Row, 1977:320. iii

The term Hindu is largely a British colonial invention that, in some ways, is meant to cover most if not all indigenous faith traditions from the Indian subcontinent. Sikhs and Jains have been somewhat successful in distinguishing themselves from this broad category. Many other faith communities simply accept the designation while others struggle to reject this label. Dalits are among the more vocal. Still, an extraordinary philosophical literature and a rich ritual tradition has developed over several millennia that are more or less linked through a number of common sensibilities. In this sense, the term holds enough relevance for our purposes here. In any case, we are stuck with it for now.

Khajuraho, 11 century, northern Madya Pradesh (southeast of Delhi); Mahabalipuram, 8 century, northeastern Tamil Nadu (south of Chennai); Dakshineswar, 19th century, eastern bank of the Hugli River (south central Kolkata). v Lindsay Jones notes that, “…for most Hindus, the focus of their ritual lives was not the famous temples but the small altar that existed in virtually every private home.” in, The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture: Experience, Interpretation, Comparison (Volume I), 2000: p.141.