Isabel Potworowski

Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism, Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada isabelpotworowski@cmail.carleton.ca

How does architecture provide a place for social interaction and spiritual renewal? This question was a central theme in the fourth-year undergraduate architectural design studio “Sacred Space | Sacred Place” that the author recently developed and taught. Students explored the relation between space, place, and the sacred through the design of a sanctuary, understood as an architectural intervention that frames and brings into focus significant qualities of place.

Space, Place, and the Sacred

The notions of space and place introduced in the studio refer to the writings of Chinese- American geographer Yi-Fu Tuan (1930-2022), who describes place as a discrete, structured, familiar and meaningful unit within the surrounding undifferentiated “space.”1

The “sacred,” on the other hand, has traditionally referred to objects or places that are “consecrated” or dedicated to a deity, and are therefore protected, isolated, and set apart. It has also been defined in opposition to the profane. However, if the sacred is considered in a less dualistic and limited way, one might recognize all of reality as potentially sacred. As well, considering the sacred in a broader sense, without strict reference to the divine, we might say that places become sacred when, because of their significance, they are set apart or elevated from our everyday reality.

The studio explored the connections between place and this broader conception of the sacred. It posited that there are places in which, through our awareness and connection to them, we can orient ourselves both physically and ontologically. This kind of orientation, as argued by American comparative religions scholar Lindsay Jones (1954-2020), is the fundamental religious question, and is one of the main functions of architecture; it implies finding one’s place in the world, in space and time.2 Mexican-Canadian architectural historian Alberto Pérez-Gómez has proposed, along similar lines, that “transcendence” can be understood as an awareness of being part of the environment, “a larger whole, even though this whole may not be intellectually understood.”3 The experience of being oriented and connected in this way could be described as one of wonder, awe, silence, transcendence, nostalgia, and desire in front of something that seems close to us, even a part of us, yet that remains beyond, ungraspable, ineffable. A place could be said to be sacred when used and experienced in this way; it is, then, a mediator of transcendence.

Architecture that sets places apart to be experienced in this way relates to the notion of sanctuary. The Latin term sanctuarium denotes a container for keeping sacred things. For Jones, a sanctuary sets a place apart and acts as a focussing lens, allowing what is within – or perceived from within – to be experienced as sacred.4 However, whereas Jones intends a “hermetic refuge of sacrality,”5 the studio considered the sanctuary as connected to the surroundings, as a lens that puts significant qualities of place into focus and orients us towards them. This conception of the sanctuary builds on the idea that, if all of reality is potentially sacred, then the role of architecture as a “mediator of transcendence” is to reveal the sacredness of a given place to our experience.

How does architecture present the sacredness of a place? How does it act as a sanctuary, mediating an experience of transcendence? It does so through both physical architectural properties – including spatial geometry, materials, light, paths and thresholds – and through the ritual actions that it frames. In this studio, ritual actions were understood as intentional actions, carried out by an individual or a group, that heighten one’s awareness of and connection to place.

A central element of the sanctuary was a gathering space for the local community, recognizing that the relation between the individual and the divine is most directly mediated by other persons, as American architect and scholar Michael Benedikt has written,6 or, in the words of German Lutheran theologian and comparative religionist Rudolf Otto (1869-1937), through “transmission by living fellowship.”7 Architecture can be a significant setting for such an encounter. It can foster a sense of community with an orientation towards the beyond. In designing gathering spaces, students were asked to consider contemporary approaches to procession and ritual, and how such activities shape one’s physical and ontological sense of orientation, contributing to a communal experience of the sacred.

Studio Methods and Design Task

Starting with the framework of concepts outlined above, the studio presented students with a diversity of perspectives about sacred space and place, encouraging them to form their own position on these topics. The studio was composed of four assignments: a text study, precedent study, site analysis, and design of a sanctuary.

Students began by presenting a scholarly text on these topics. They were prompted to consider the types of buildings and places that might constitute a sanctuary, the relation between sacredness and place, and the role of movement and ritual in the experience and creation of sacred space and sanctuary, among other questions.

Then, in pairs, students carried out a precedent study of what they considered to be a sanctuary. Their personal experience of the place was significant in this study, which is why the precedent had to be one that they had visited or could visit. Observations made by the students include the spiritual energy that seemed to emanate from the rushing water at a site that is sacred to the Algonquin people, the “civil sacredness” of the monumental Senate building, and the “otherworldly” experience of walking through a cemetery.8

Following these two introductory assignments, students chose a project site in Ottawa. In addition to an “objective” site documentation including plans, sections, as well as historical and current uses, they were asked to identify and describe significant qualities of their chosen sites that affect or reveal their sacredness. They did so through a photo essay and through sketches, videos and other representations that communicated a sense of place. Based on these observations, they built evocative site models that let the sacredness of the place speak, focussing primarily on how materials can bring out the atmosphere of their sites.

Approaches to making site models included using tree bark, CNC milling topography onto a tree trunk slice, and representing water with layered watercoloured transparencies.

Taking the site analysis and model as a point of departure, students then designed a sanctuary as a focussing lens for the identified qualities of place. There was no required area or set program, but the project had to include spaces for indoor and outdoor gathering, individual contemplation, and an entrance path and sequence. These areas were to include a space for exhibition and/or remembering, a space for experiencing the site, and two additional functions from among the following: a spiritual retreat, a chapel, a community outreach function such as a meal service, a performance or event space, or another function that they deemed appropriate for the site. The final design was presented through architectural drawings, as well as through physical models of the overall intervention and of a significant space or tectonic detail.

Selected Student Work

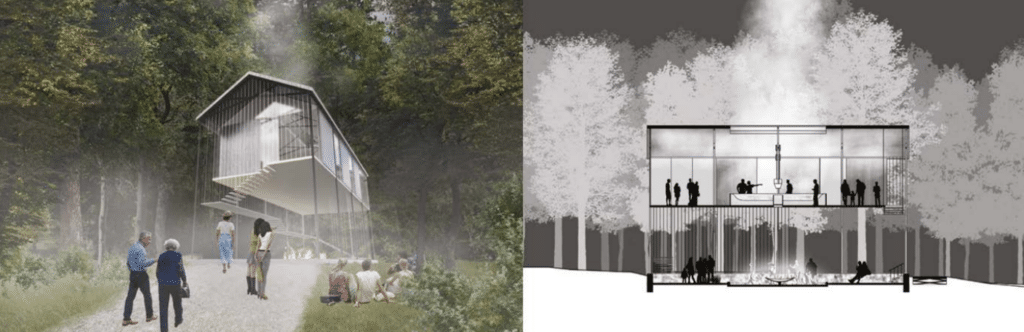

Three examples of student projects demonstrate how these questions were approached. In the first project, the students, Ty Follis and Bianca Hacker, preserved the remains of a recently burned sugar shack on their site and designed a gathering space as a light “soul” rising from the “dead” ruins, with a fire continuously burning in the footprint of the old structure. Their addition re-interpreted the process of making maple syrup, highlighting its ritual and sacred aspects to the indigenous people.

Figure 1: “Ascension” by Ty Follis and Bianca Hacker. ©The students and Carleton University.

The second project by Gavin Bailey, Sasha Borwick, Jackson Flagal and Jacob Wilson proposed community and contemplative spaces along the banks of a river containing the ruined piers of a former railway bridge, as well as a new pedestrian bridge that left the old piers exposed.

Figure 2: Proposal including two connected projects: “Ontological Observatory” by Jackson Flagal and Gavin Bailey, and “Between the Stones” by Sasha Borwick and Jacob Wilson. © The students and Carleton University.

The third project by Elizabeth King is a procession along a river that includes larger pavilions at the beginning and end, and three more intimate pavilions (“forest,” “river,” “edge”) that provide different experiences of the water; it proposes that experiencing the sacred requires one to be invested in one’s environment.

Figure 3: “The River Procession” by Elizabeth King. © The student and Carleton University..

Concluding Remarks

These projects show how architecture can foster spiritual renewal: giving form to ritual actions, framing ruins as a reflection of mortality and existence, and designing a processional path. They show how a sanctuary can act as a ‘mediator of transcendence’: not being transcendent in itself, but mediating – that is, framing and providing a setting for – an experience of the greater transcendent whole to which we belong. It is a whole that we can intuit through an awareness of the sacredness of our environment and our place within it.

1 Yi-fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota press, 2002), 6.

2 Lindsay Jones, The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture: Experience, Interpretation, Comparison, vol.2 (Harvard University Press, 2000), 26–31.

3 Alberto Pérez Gómez, Attunement: Architectural Meaning after the Crisis of Modern Science

(Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2016), 228–29.

4 Jones, The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture, 2000, 2:264–67.

5 Lindsay Jones, The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture: Experience, Interpretation, Comparison, vol. 1 (Harvard University Press, 2000), 265.

6 Michael Benedikt, ‘On Architecture, Divinity, and the Interhuman’, in Architecture, Culture, and Spirituality, ed. Thomas Barrie, Julio Cesar Bermúdez, and Phillip Tabb (2015; repr., Routledge, 2016), 16.

7 Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and Its Relation to the Rational, trans. John Harvey, 7th ed. (1917; repr., London, UK: Oxford University Press, 1936), 63.

8 The notion of the “civil sacred” is based on the article by Matthew T. Evans, ‘The Sacred: Differentiating, Clarifying and Extending Concepts’, Review of Religious Research 45, no. 1 (September 2003): 32–47.