Karen L. Mulder

Corcoran College of Art + Design, Washington DC

klmulder@mindspring.com (preferred); Karen_Mulder@corcoran.edu

As I began researching a unique postwar German arts movement in 1992, various terminological and disciplinary disjunctions confronted me. The experience subsequently converted me into an advocate for multidisciplinarity as the best tool for investigating architectural function through time. My subject focused on an unexplored trend among German designers commissioned to replace monumental window arrays on historic sites after 1959, particularly in nationally significant sanctuaries. More than 70,000 historical churches in West Germany required renovation or total reconstruction after the war; vaults and glass were the first casualties.

The designers I studied insisted that their concepts were “architectonic.” In the end, this ‘architectonic’ glass provided the portal to a much broader consideration, related to the ways that meaning changed after Auschwitz, in spaces considered sacred to the nation’s identity. The greatest terminological issue related to “architectonic,” which translates quite differently in

German than English, although ACS members could hardly avoid the quandaries of using

“spiritual,” “sacred,” or “religious” as qualifiers for spatial quality. In English, “architectonic” refers generally to ‘aspects related to architecture’ or structural quality. In German, however, architectonic relates to the concept of Raum, used by Giedion in the epic 1950s text, Space [Raum], Time and Architecture. Raum in its fullest Germanic sense constitutes a physical container for interiority, and interiority incorporates a shifting physical experience due to ambient light, progression through the space, or materials. This interiority also relates to a psychological state of mind that changes as ambience, light, or depth acts upon it, making some Räume more sublime than others, or necessitating distinctions in spatial treatments for differing purposes. In the end, the architectonic designers concluded in their manifestos that light was their actual material, glass the actuator for the material, and Raum the combustion chamber for the interaction between them. They dismissed painters, like Chagall, who simply used glass as a ground for painted pictures.

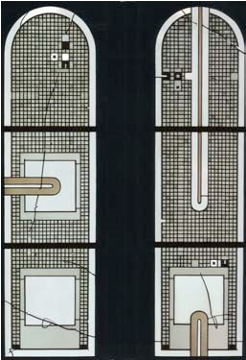

Johannes Schreiter, restoration of 12th-century St. Nikolaikapelle, Soest with 1995 windows. Frankfurt Dom Wahlkapelle, with arrow indicating place of emperor’s election, and crown icon.

Disciplinary disjunctions arose as I realized that stained glass, as both craft and practice, has not been theoretically engaged since the 19th century. By the mid-1990s, a handful of theoretical or in-depth academic reassessments began to emerge about the broader societal implications of culture on art and architecture, and some fleetingly took glass programs into account. Texts like Artistic Integration in Gothic Architecture (1995), or Medieval Architecture, Medieval Learning by Radding and Clark (1994) cleared away some of the obstacles to a broader discussion of the historical European sanctuary as a design complex or ensemble, rather than a discrete construction influenced by abstract ideologies on the one hand, or the idiosyncratic choices of masons, patrons and builders on the other.

A handful of German-language preservation surveys and the Allied strategic bombing report occasionally focused on ecclesiastic complexes, but frequently differed in statistics and conclusions, forcing me to wade through reams of material to pick out incidental facts or anecdotal information on specific church properties. In any case, the rhetoric of any preservation assessments made during the first two decades after the war wavers between the triumph of restoration in the face of defeat and physical devastation, tempered by Germany’s need to project humility and humiliation after the massive transgression of the Holocaust. Moreover, the sources for postwar church rebuilding relied on local, therefore inconsistent recordkeeping between Catholic dioceses or Protestant parishes. For the most part, the majority of German ecclesiastic buildings were overshadowed by the hegemony of the French Gothic lineage, and marginalized as regional, idiosyncratic, and even retardataire in the larger discussion until the 1990s.

Curiously, the most salient analyses available for postwar Germany’s situation came from authors who were not concerned with art or architectural history. Contributors included, for example, Judaica professor James Young on post-Holocaust monuments, anthropologist Rudy Koshar’s analyses of Germany’s tourism campaigns during reconstruction, and Berlin-based journalist Michael Wise’s assessment on the German government’s stylistic choices during the rebuilding phase. The German discussion broadened out significantly by the late 1990s, with anthologies on collective memory and national identity. These assessed Germany’s disparate postwar preservation strategies as attempts to remount a positive German narrative in the eyes of the watching world. Four decades after the war, however, historians finally began commenting about how regionally iconic churches represented local culture, stability in the landscape, tourist dollars, and structures that engendered regional patrimonial value as civic heritage sites.

The most active and historically valuable complexes are characterized by continuous alterations in physical fabric, function, and patrimonial status. Many had monastic foundations, expanded by royal sponsorship, and many linked to academic enterprises. Others served as the stage for royal events, such as coronations or imperial processions, occasionally morphing into venues of 19thcentury democratic proclamations–all relevant to German notions of national identity. Many suffered from stylistic ‘purification’ campaigns (Reinigungen), which ‘modernized’ or updated medieval features to baroque to neo-Gothic styles and back before the 20th century. After the Reformation, many sanctuaries were physically converted from Catholic to Protestant spaces, and some even served both denominations simultaneously, by royal decree, until the Nazi regime shuttered them in the late 1930s. No major church foundation escaped devastating fires or incendiary damage, culminating in the greatest amount of ordinance ever targeted on one country with the Allied bombing campaign. After the war, site renovations frequently entailed a process called ‘sanitization’ [Sanierung], which rebuilt ruins to their purest medieval iterations to reinforce Germany’s proudest moments in history, before The Great War defeat, Hitler, and the Holocaust. Consequently, ‘medieval’ churches like St. Gereon in Cologne, although rebuilt as faithfully as possible to its classic 10th-century decagonal format, are actually less than 70 years old today, bringing up troubling issues of ‘authenticity’. Finally, with dwindling congregations unable to afford responsible restorations (let alone winter heating bills) in huge sanctuary spaces designed to house entire towns or cities, naves have become performance venues, charging entrance fees or promoting high level concert programs that bring revenue in the door.

Because the historical record is so jumbled, and because Germany’s complicity in the Holocaust still constitutes an embarrassment—resulting in the omission of war-related information—our ability to uncover the most accurate narrative for such altered spaces poses a huge challenge. Ultimately, there is no concerted source for an in-depth historical assessment of most German sanctuaries. The architectonic glass designers opted to provide hints, in their windows, of the former relevance, dignity, and value of such places, by reconstructing the architectural narrative of each host site. The ensemble emphasis came naturally to artists trained in the German art educational system, which had insisted for decades on the ideal of totalizing art (the

Gesamtkunstwerk), on applied rather than solely fine arts platforms, and as Gropius preached, on architecture as the unifier of all the other arts.

For scholars, however, the only way to fill the gaps for this postwar context involves sieving through a multidisciplinary array of resources. My conclusions, in the end, owe everything to a fully contextualized historical and socio-political understanding of Reconstruction Germany, and very little to art historical purviews on stained glass, which remain pinned to a 19th century formalist model.