Rumiko Handa University of Nebraska-Lincoln rhanda1@unl.edu http://architecture.unl.edu/people/bios/handa_rumiko.shtml

For some time now architects have operated with the notion that the building is finished when the construction is complete and that any subsequent changes are degeneration. Similarly, architectural criticism often focuses on the architect’s intention and how it has been met by design and execution, and architectural history explains a building through the sociocultural context of the original construction. The history of art and architecture, however, is not devoid of cases counter to the notion of completeness, perfection, and permanence. Michelangelo’s last piece, Rondanini Pieta, unfinished at the time of the artist’s death, has always drawn much interests.

Architectural ruins have promoted the poets and novelists, including William Wordsworth and Sir Walter Scott, to create the imaginary worlds. At our time the works of adaptive reuse seem to work even better than did originally.

Japanese aesthetics of 侘び寂び (wabi-sabi) – the imperfect, incomplete, and impermanent – based on Zen Buddhism and exemplified in the works of sixteenth-century tea master 千利休 (Sen no Rikyu, 1522-1591) is another that counters the predominant notion. One of the most important aspects of Japanese way of life, wabi-sabi is discussed from the rudimentary level of tourist guidebooks to the scholarly discourse of philosophy. Nevertheless wabi-sabi is often elusive. Rikyu never produced a comprehensive treatise, following Zen Buddhism’s teaching that the enlightenment is attainable by sitting meditation away from scriptures. Only after the grandson’s death Rikyu’s teaching was recorded. This paper relies on Rikyu’s letters, disciples’ texts, contemporary scholars’ interpretations, extant tea wares, and, above all, 待庵 (Taian), the only tea room by Rikyu that still exits. Rikyu’s elusive teaching explains what I have called participatory interpretation, that is, the type of interpretation whose goal is not so much to obtain original meaning hidden behind the text as to search what Paul Ricoeur called “the world of the text” in front, which “I [the interpreter] could inhabit and wherein I could project one of my ownmost possibilities.”

Taian consists of a six-foot square tea room, with an additional raised floor 床 (toko), the anteroom 次の間, and the preparation space 勝手.[1] Rikyu’s ideal hermitage was nine-foot square at the largest, an intense, rather than perfectly comfortable, space to invigorate one’s senses.2 The same principles apply to Rikyu’s pottery, 楽 (raku) (figure 1).[2] Molded by hand rather than on a potter’s wheel, raku never achieves perfect circle or uniform thickness. Its low firing temperatures results in a porous body. To attain its color, the piece is plunged into water directly from the kiln while still glowing hot. Many pieces break at this point. Rikyu chose to submit man’s art to the natural forces of earth, fire, and water.

Rikyu’s refusal of man as the creator of perfection extends further to let the artifact fail its primary utility. A guest informed Rikyu that his flower pot was leaking water.[3] He replied, “this dripping water is the life.”[4] The pot in question made of bamboo by Rikyu is extant (figure 2). The crack developed in the course of time was a proof of life, while an object remaining in its perfect state was dead. Many other anecdotes tell Rikyu’s predilection to place nature above perfect craftsmanship: He would sweep 露地 (roji), or the garden passage, much in advance to allow some leaves to fall before the guest’s arrival.[5] He would arrange imperfect stones, not in a perfectly straight line but in an irregular manner.[6] Taian used un-hewn logs, with some bark still remaining, to frame the space over the toko while the typical material would have been smooth rectilinear timbers. Taian’s walls were of mud mixed with cut straw. The two windows in the eastern wall are in different sizes and do not line up in any regular relationship.

Figure 1: Raku Chojiro, 大黒 (Oguro) in black raku and 早船 (Hayafune) in red raku

Figure2 : Sen Rikyu, 竹一重切花入 (Take Ichiju Kirihana-ire)

Rikyu would have been satisfied to live in the deserted mountains if he were with a flower vase, a tea cup, and a piece of calligraphy.[7] This explains Rikyu’s idea of wabi, in which the mind’s eyes pursuing for what may never exist would be more fulfilling than the ocular eyes actually encountering a beautiful object.[8] 筒井紘一 (Tsutsui Hiroichi), the contemporary scholar, compares it with Silk Road, whose allure is based not on the actual landscape but on the distance that holds our imagination without visiting it. Two of Rikyu’s favorite poems demonstrated the sentiment: “見

わたせば花も紅葉もなかりけり浦のとまやの秋の夕ぐれ” (Look around, no flowers, no colored leaves. A cottage in a seaside village, in autumn sun set.)” and “花をのみ待たらん人に山ざとの雪間の草の春を見せばや” (A person waiting only for flowers. Let him see a spring in a grass emerging from the snow, in a mountain village.)”[9]

Guests needed to be readied to look for beauty in an unlikely place. Rikyu stated that the principle of tea is only to boil water, make tea, and drink it, recommending to rid of the selfinflicted desires.[10] Rikyu set the water basin 手水鉢 (chozu-bachi) in roji so that the guests had to lower themselves to wash their hands, readying themselves for the forthcoming experiences of tea. The tea proceedings has specific moments in which the guests are to observe artifacts. Raising the eyes from the crawling position through the entrance 躙り口 (nijiri-guchi), the guest confronts the art object over the toko. The movable shelves were eliminated from small tea rooms and the tea wares were directly placed on the floor, to focus the guests’ attention.[11] The wall corners at which the host makes tea and over the toko are rounded, whose purpose according to contemporary scholars is to make the small space appear larger; however, it would make more sense that the rounded corners were to hide the wooden frames, which otherwise would have taken the viewers’ attention away from the tea wares or the toko.

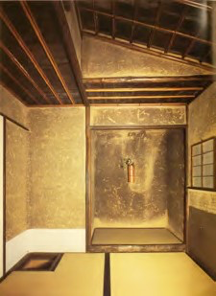

Once the sliding doors are closed Rikyu’s tea room creates its own world (figure 3) quite different from the normal Japanese spaces, in which the interior and exterior have no explicit boundaries.13 With the yellowish gray mud walls oozing out black charcoal, and with rice paper screen over the windows, Taian is more like an earthy cave, which helps the guest to rid of one’s earthly desires and willfulness. It does not shut out the outer world entirely, however. The sun and the clouds outside change the shadows of the window mullions. One hears birds chirping and leaves fluttering. The guest is drawn to the participatory interpretation of the outside world, which may not exist beyond the walls, but could be imagined.

Figure 3: Sen Rikyu, Taian, looking toward the toko.

In conclusion, while considered inferior as an art object, the incomplete, imperfect, or impermanent may have an effect on the viewer, which the architect cannot ignore, enticing the participants in the imaginary interpretations that are significant to the viewer’s ontological understanding of the world and the self.

[1] Meiji, Momose(百瀬明治), ”国宝の茶席,” 庭と茶室: 華やぎとわびさびNiwa to chashitsu: hanayagi to wabi sabi. ed. by Harada, Tomohiko (原田伴彦) (東京: 講談社, 1984), 148-151. 2 Isao Kumakura (熊倉功夫), 南方錄を読む Nanbōroku o yomu (京都: 淡交社, 1983).

[2] Sen Sōsa and Sen Sōin, ed. 千宗左監修 千宗員編, Kōshin Sōsa chasho 江岑宗左茶書 (Tōkyō : Shufu no Tomosha 主婦の友社, Heisei 10 [1998]), 79.

[3] Kōshin Sōsa chasho, 79.

[4] http://nobunsha.jp/meigen/post_107.html (03/23/2011)

[5] Kōichi Tsutsui (筒井紘一), “茶数寄の庭,” 庭と茶室 : 華やぎとわび.さびNiwa to chashitsu: hanayagi to wabi sabi. ed. by Harada, Tomohiko (原田伴彦) (東京: 講談社, 1984), 115-124.

[6] 無住抄, quoted in Kōichi Tsutsui (筒井紘一), “茶数寄の庭,” 庭と茶室 : 華やぎとわび.さNita to chashitsu: hanayagi to wabi sabi. ed. by Harada, Tomohiko (原田伴彦) (東京: 講談社, 1984), 121.

[7] Kōshin Sōsa chasho 江岑宗左茶書

[8] http://www.omotesenke.jp/chanoyu/3_2_2.html

[9] Nanbo-roku 南坊録

[10] Shirō Senga 千賀四郎 ed., Sen no Rikyū 千利休 (Tōkyō: 小学館, 昭和 58 [1983]), 2.

[11] 西沢文隆 insert, 千利休 Sen no Rikyu by Shirō Senga (千賀四郎) (東京: 小学館, 1983). 13 西沢文隆 insert, 千利休 Sen no Rikyu by Shirō Senga (千賀四郎) (東京: 小学館, 1983).