Ben Heimsath

Heimsath Architects, Austin, Texas

benh@heimsath.com

www.heimsath.com

The ability of a built environment to convey a sense of spirituality may be significantly influenced by the expectations of its makers provided they have an appropriate process to create their space. A congregation may embrace a fully collaborative process as a way of contributing to the spirit of a place. In more than twenty-five years of work with faith groups from many diverse backgrounds and denominations, the author has developed a process for design and project implementation based upon a fundamental belief in the ability of groups to find spirituality in their design solutions.

This highly interactive process includes a collaborative session, or Design Retreat Workshop, which utilizes many established community design principles whereby people are actively engaged in various stages of the design process [1]. Held in a neutral setting, the Design Retreat Workshop includes components of both a leadership forum, and a problem-solving charrette. However, unlike these traditional formats, the event is compressed into one day, and the architects and congregation leaders participate equally in generating design ideas. The overall problem is generally defined and typically includes a range of facilities issues and program needs. The goal for the session is simple; everyone present must feel that the group, in the end, has developed one solution that is “best.” A major advantage of the early contributions made by congregation leaders is that the creative interaction continues throughout the rest of the design and building implementation process. Many significant contributions come from ideas generated or refined from this early session.

The Wisdom of Crowds, by James Surowiecki presents extensive economic and sociological research documenting numerous ways that groups of people, large and small, outperform even the most talented individuals in predicting and problem-solving [2]. Surowiecki however, offers little insight to the reason this happens. When individuals gather together and find a connection or common purpose, the experience can become so tangible that it may be felt or expressed as a presence in the group. In the course of many Design Retreat Workshops, this energy has been called many things, based on the terminology of various religious traditions. These creative experiences seem to embody the genius of communal worship. Each experience is remarkably similar, regardless of what it is called.

A case study of the Unity Church of the Hills illustrates the process with the creation of a successful spirit-filled environment. This project involved the relocation of the church to a new, undeveloped site. The process for Unity’s design and implementation typifies the author’s general approach to working with congregations and provides an opportunity for commentary.

Unity Church of the Hills, Austin, Texas

In 1999, two-dozen congregation leaders assembled at a local restaurant reserved for the Design Retreat Workshop. Structured discussions focused on what made the two-and-a-half year-old ministry special. Participants assessed information from a previous small group tour of the existing facilities that helped to generate priorities for the new fourteen-acre site.

The morning exchanges helped to identity the spirit that members felt within the congregation. While many groups describe this spirit through stories of their history, the Unity Church group stressed the connections members had already made with the undeveloped property. One participant shared his revelation when he saw the seller’s name, Guthrie O’Donnell, abbreviated as “G O’D” on the subdivision documents. Nearly everyone described a feeling of peacefulness under the canopy of trees even though buildings surrounded the property on all sides.

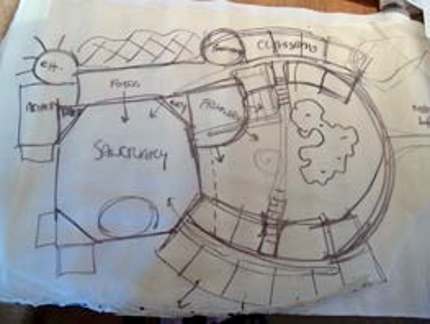

In the afternoon session, the architects explained that the group should consider itself the authors of the final design. The architects noted that they would be refining the concept, but the basic plan would emerge from this retreat. The Unity participants were separated into three brainstorming groups and asked to work with one of the architects to imagine as many solutions as possible. Each group was assigned a blank site plan and set of scaled templates representing potential programmed spaces. By the end, eleven sketches adorned the walls. Participants took a break, and then reassembled to hear each sketch explained by one of the members who drew it. A straw poll was then taken in order to focus the remaining conversations on those solutions most favored by the participants.

Two preferred plans located buildings in the same clearing near the center of the site. They both featured circular plans for the sanctuary. The architects explained that the circle is associated with sacred geometries, and that Renaissance builders saw the circle as a perfect form. The ministers noted that the circle is a powerful symbol in the Unity theology. One plan showed a large entry arch over the narrow drive connecting to the main commercial street. The other featured a masonry wall that parted to emphasize the transition from the parking area to the interior of the site.

The architects suggested ways to merge the two solutions. The entry arch and the parted stone wall could both be used to create a path symbolic of the spiritual journey towards worship. The building placement and the circular sanctuary shown on both plans could become an octagonal plan. The architects noted that saving trees was a consensus priority of nearly all the solutions. They re-sketched a synthesis plan and included the small circular chapel at one end of the entry wall.

Sketch Plan

The session ended with an affirmation by each participant that the group had developed an inspired design for the property. The ministers, in their closing prayer, cited Unity teaching in describing the powerful goodness of God that had been present in the day’s proceedings.

The plan sketch from the Design Retreat Workshop closely resembles the completed building, featuring an octagonal sanctuary that stands on the site today. The collaborative process continued to produce fruitful results. Only four trees were removed to accommodate the parking, drives and building. The entry arch concept violated numerous codes, but variances were approved unanimously by City agencies. At the present time, the architects have begun planning for an expansion of the original building. Congregation members, however, want to be sure there is no loss or damage to the great feeling of spirituality that exists in the building and on the property. Utilizing the same collaborative process, there also is great confidence that the spirit of the place will remain.

Completed Building Plan

Commentary

Most architects are not trained to share their design process with groups. They often see creativity as an individual effort that is only compromised by outside participation. This approach can cause strained relationships particularly when the client is a church or spiritual community. This unwillingness to share seems particularly incongruous when considering how many architects equate the creative spark with divinity, even suggesting the process of design creativity as a metaphor for understanding God [3].

Theologically, most contemporary denominations don’t believe their buildings contain God.

Rather, they share some form of the belief that God is present when “two or more are gathered in God’s name.” As the Unity process illustrates, something special also happens when people gather to design in God’s name. The sense of spirituality so greatly appreciated by the congregation today, has its roots in the spirituality experienced by its members engaged in the process of creating it.

Unity Church of the Hills, Austin, Texas

By Heimsath Architects, Dedicated 2001.

References

- Henry Sanoff, Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning (New York: J Wiley & Sons,

2000)

- James Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds (New York: Anchor, 2004) Surowiecki doesn’t include the activities of planners and architects in the growing field of community involvement in design, though conceptually, it raises the same issue. Evaluation of design quality may be subjective, but specific criteria, such as the satisfaction of the users of the completed building could be used.

- Michael Benedikt, God, Creativity, and Evolution (Austin: Centerline Books, University of Texas at Austin,

2008), pp. 38-39, 42-54. Benedikt continues in his writing to offer an intriguing argument for a definition of God based on the creative designer metaphor. This reference, however, is made only to demonstrate the connections historically that architects have made between the Devine and creativity.