Anat Geva

Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas A&M University, College of Architecture a-geva@tamu.edu

The second commandment “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” was interpreted through history as a restriction of any artistic creation to be part of synagogues. In addition, periods of hostility of the outside world prevented Jews to glorify the exterior of their synagogues in the diaspora. Art and artifacts in synagogues were confined only to liturgical objects and were considered as functional religious items, which were labeled as Judaica art and craft.[1][2] The significance of artwork in synagogues and its acceptance by congregations and their leaders started to be notable post WW II in America, as part of Jewish search for their identity.[3] This search was influenced by the events of the holocaust, the establishment of the state of Israel, and the realization of the American value of freedom of religion.[4] Congregations and their leaders perceived modern architecture and American Abstract Expressionist Art[5] as enhancing their physical and spiritual exsistance. Some claim that it was the time of awareness of the mutual relationship between religion and art as lifting the Jewish soul and as essential to Jewish survival.[6] The move of congregations to the suburbs during that era enabled them to start a-new and build their synagogues as a modern institution that manifested the American Jewery identity through architecture and art.6 This paper illustrates the influence of this context on the collaboration between sacred architecture and art in modern American synagogues, and how artists saw Jewish and biblical themes as an extension of their general Abstract Expressionist imagery. The following six examples exhibit the variety of this collaboration.

Eric Mendelsohn’s article In the Spirit of our Age,[7] and his synagogue designs were among the first to reflect congregations’ desire to depart from historicism and express American values and modernism. Influenced by Mendelsohn’s manifest other prominent architects (Frank Lloyd Wright, Philip Johnson, Walter Gropius, Percival Goodman, Marcel Breuer, Minoru Yamasaki) ventured to bridge modernism and Judaism in their design of the American synagogue, and to link the building to the American landscape and values. Their attempts also introduced artworks as part of synagogues’ architecture and as an abstraction of faith symbols that would enhance spirituality, community,[8] traditional values, and self-image. Studying this collaboration reveals two approaches in incorporating art in the design of the modern American synagogues: (a) the architect creates the artwork as part of the architecture of the building, and (b) the architect commissions artists to integrate their artwork as part of the synagogue’s architecture.

The architect creates the artwork as part of the architecture of the building

Architects such as Mendelsohn, Wright, Gropius, and Yamasaki perceived art as an organic part of the synagogue’s architecture and as part of their interpretation of faith traditions. Their holistic design approach was illustrated by their design of the interior features and artwork, such as the Bimah (stage), the Ark, the eternal light, and the sanctuary’s furniture. For example, Mendelsohn designed the focal point of the sanctuary in Park Synagogue in Cleveland, Ohio as a wooden mahogany Ark under a wooden canopy (Fig. 1). He used the letter “shin” from the Hebrew alphabet as the main decorative motif on the Ark’s doors, and the menorah — a Jewish symbol of light and freedom that he designed from metal. Although this Hebrew letter seems simple but symbolizes the different names attribute to God. In addition, he also designed the synagogue’s eternal light as a circular metal chandelier to represent eternity. Thus, Mendelsohn introduced his interpretation of faith symbols and biblical terms as an integrated part of the sanctuary.

Figure 1: Mendelsohn’s design of the Ark: Park Synagogue, Cleveland Ohio.

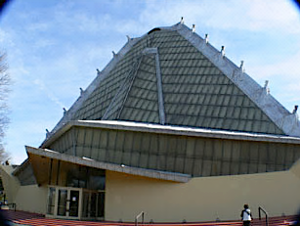

Frank Lloyd Wright called for abstraction of faith symbols using metaphors related to religious traditions and myth and integrated them into America.[9] In Beth Sholom Synagogue, Elkin Park, Pennsylvania, Wright combined Native American symbols and art of tribes that lived in the region with Jewish symbols. As such he wedded the American spirit into the ancient spirit of Israel.[10] For example, he considered the pyramidal shape of the synagogue to resemble Mount Sinai where the Ten Commandments were given to the people of Israel, but also as the Native American tipi (Fig. 2). The decoration on the three sides of the building’s exterior tripod consists of an abstracted form of a menorah, while the pattern of each of the menorah’s seven ‘candle holders’ is an abstraction of a Native American art motif. This demonstrates the integration of artistic motifs into the synagogue’s functional structural system. In the interior Wright continued to use the triangle as the module/form for all part of the synagogue. This geometry is the base for his design of the sanctuary’s chandelier. A stained glass triangular was inspired by Jewish mysticism (Kabbalah) where each color manifests human’s virtue.[11]

Figure 2: Wright’s Beth Sholom Synagogue, Elkin Park, Pennsylvania.

The architect commissions artists to integrate their artwork as part of the synagogue’s architecture

Other architects like Percival Goodman, and Philip Johnson took a different approach to incorporate art in their synagogues. They commissioned Jewish artists and collaborated with them to include their artworks in the synagogues. This approach is seen as the beginning of a Jewish tradition of integrating visual/plastic art in synagogue design. In Goodman’s article published in Commentary, he acknowledged that none of the rising Jewish artists of modern times has ever worked in religious buildings, though they expressed their interest in interpreting “Biblical archetypes, the Prophetic tradition, and the simple sublime spirituality of Jewish theology.”[12] Goodman provided architectural spaces /frames for the artwork, where the artists could articulate their own themes, without being dominated by the architecture.[13] For example, in one of his first designs, Congregation B’nai Israel Synagogue in Milburn, New Jersey (1950) Goodman had collaborated with three emerging, avant-garde Jewish artists of that time to decorate that building.[14] Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell, and Herbert Ferber created abstract expressions with different media and techniques for the fabric Torah curtain, for a lobby mural, and for an exterior metal sculptural relief, respectively. They abstracted Biblical themes to express the twelve tribes, the menorah and the phrase “the bush was no consumed” (Fig. 3).[15] It is assumed that Ferber’s sculpture of copper sheeting covered with soldered lead and strengthened with brass, and its integration into the synagogues’ architecture paved the way to consider sculptures as the most effective art form for modern American synagogues.16

Figure 3: Congregation B’nai Israel Synagogue, Milburn, NJ: Ferber’s exterior sculpture.

In 1956 Philip Johnson commissioned Abram Lasslaw to sculpture the Bimah and the eternal light for Kneses Tifereth Israel Synagogue in Port Chester, New Yorkas a background for Johnson’s design of the Ark (Fig. 4). Lasslaw, as other sculptures of the time, introduced a new technique of direct-metal construction that was developed after WWII. The acceptance of his metal art indicated the congregation’s commitment to progressive artists.[16] However, recently this art was disassembled and sold with Johnson’s Ark and chairs to the National Jewish Musuem in New York. Apparently, the new generation did not connect to this modern abstracted artistic piece, claiming that the wired relief reminds them of a concentration camp fence, and the eternal light of pagans’ worship of the sun. They shifted to a more conservative liturgical functional art made of Jerusalem stone and concrete that expresses the longing for Jewish roots (Fig 4). This example raises the question of the role of ‘timeless’ religious symbols and how they may change through time.

Figure 4: Kneses Tifereth Israel Synagogue, Port Chester, New York (L- Lasslaw’s sculpture of the Bimah and the eternal light and Johnson’s Ark; R- today’s Bimah)

Other impressive examples are the abstracted stained glass wall of the Chicago Loop Synagogue (1957) by artist Abraham Rattner, and a bronze and brass sculpture by artist Henri Azaz at the synagogue’s entrance (Fig. 5). The architects Loebl, Schlossman, & Bennett collaborated with the artists not just to beautify the synagogue, but also to bolster worshippers’ spiritual experience. They dedicated the eastern wall facing Jerusalem to a liturgical contemporary art that depicts a universal symbol of “let there be light”.[17] The sculpture on the exterior portrays the Jewish symbol of the priestly blessing hands – the “hands in peace”. Thus, all who enter the synagogue are blessed and should come in peace.

Figure 5: Chicago Loop Synagogue, Chicago, IL (L Rattne’s stained glass wall; R Azaz’s exterior sculpture)

Conclusion

The article’s examples illustrate how the unique collaboration between sacred architecture and art in modern American synagogues expressed the Jewish faith through functional pieces of art and abstractive biblical interpretations. Talbot Hamlin introduced five principles guiding collaborations between architecture and art.[18] Architecture and art have to emphasize the autonomy and respect of each discipline in the process of collaboration. Thus, each artwork should be designed with direct reference to its specific place and to the whole architecture, while the architecture should frame its design to enhance the art’s visual effectiveness.[19] Though there is a room for many kinds of interaction, still all serve as an inspiration and pride for Jewish congregations in America.

[1] Wong Jadine Wong. 1994. “Synagogue Art of 1950s: A new Context for Abstraction” Art Journal. Winter:

[2] -43; Kampf Avram. 1966. Contemporary Synagogue Art: Developments in the United States, 1945-1965. NY: Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

[3] Schack William. 1956. “Modern Art in Synagogue II: Artist, Architect, and Building Committee Collaborate” Commentary 21 (February): 159.

[4] Sachs Angeli, and Edward van Voolen (eds). 2004. Jewish identity in contemporary architecture. München, Germany; New York: Prestel; Wong Jadine Wong. 1994.

[5] Abstract Expressionism movement started in New York city during the 1940s

[6] see note 3. 6 Sachs Angeli, and Edward van Voolen (eds). 2004; Gruber Samuel. 2003. American Synagogues: A Century of Architecture and Jewish Community. NY: Rizzoli.

[7] Mendelsohn Eric. 1947. “Creating a Modern Synagogues Style: In the Spirit of Our Age” Commentary. Vol. 3 no. 3

[8] All photos were taken by the author

[9] Geva Anat. 2011. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Sacred Architecture: Faith, Form, and Building Technology. London: Routledge.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid

[12] Goodman Percival and Paul Goodman. 1949. “Modern Artist as Synagogue Builder” Commentary (January)

[13] Kampf Avram. 1966.

[14] Wong Janay J. 1994.

[15] Rabbi Grenewald explained the concept of “the bush was no consumed” as the reflection of the fate of the Jewish people. In Ashton Dore. 1951. “Reverend Comments” Art Digest 26 (October, 15): 15. 16 Wong Jadine Wong. 1994.

[16] Kampf Avram. 1966 (p. 54); Schack William. 1956.

[17] Genesis 1:3.

[18] Talbot Hamlin. 1952. Forms and Functions of Twentieth Century Architecture. NY: Columbia University Press (p.746).

[19] Kampf Avram. 1966 (p.45)