Robert D. Hermanson

University of Utah

xtreborx@centurytel.net

“… I was often told that beauty and the sublime … are for us eighteenth century concepts defined by assumptions we no longer share. I am not convinced about the last part. Gravity is a seventeenth-century concept that continues to explain one’s body’s refusal to fly…” [1]

Beauty and the Contemporary Sublime

Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe

Abstract

Has the sublime gone? If so, where? Can the sublime go anywhere, or is it our relationship to it… our perception of it that has changed?

After the demise of Romanticism in the 19th Century and the advent of Modernism, new paradigms emerged that diminished the notions of beauty and the sublime. The increasing emphasis on a positivist notion of culture as that which is moving ever forward and upward, seems to have been fulfilled by new technologies, unknowable and thus terrifying as manifestations of a new sublime. Gilbert-Rolfe observes that “technology has subsumed the idea of the sublime because it, whether to a greater extent or an equal extent than nature, is terrifying in the limitless unknowability of its potential…” [2]

In contrast to the technological sublime, the notion of silence, a pause, but also a kind of resistance has simultaneously emerged that provides an introspective aspect suggesting an alternative sublime. Roger Connah observes: “…the possibility of silence offers not only retreat, not only refuge, but respite from the world’s excess.” [3]

These conditions provide a juxtaposition, and therefore a co-existence of qualities informing and affecting our own perceptions. But how do they co-exist? What are their conditions and their meanings in a contemporary society? In this paper I wish to address these issues and elucidate new interpretations of the contemporary sublime.

A Technological Sublime

Nature[4] (and its forces) has historically elicited emotions ranging from the beautiful and tranquil to the awesome and terrifying.

1

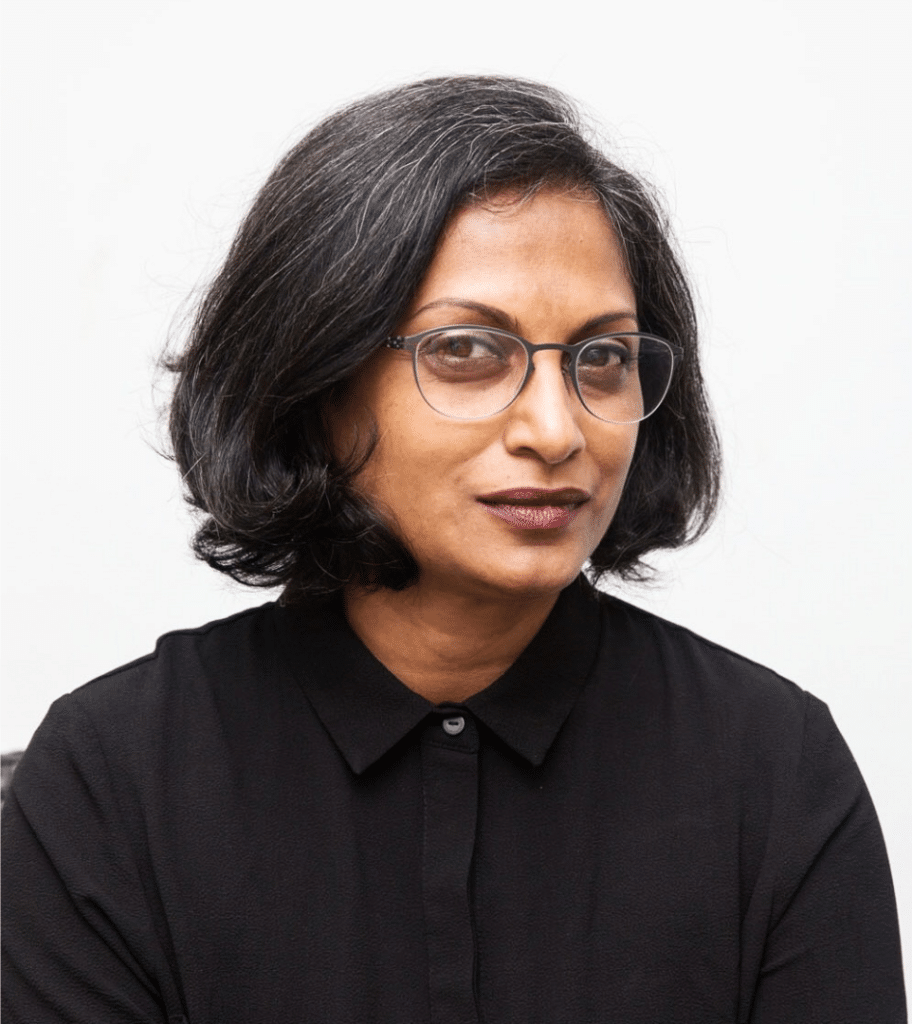

The Pass of Faido 1843, J.M.W.Turner Engadin 1995, Andreas Gursky

Two images, one by Turner in 1843, the other by the German photographer Andreas Gursky in

1995 provide contrasting interpretations of that nature. For Turner The Pass of Faido presents “grandiose evocations of the rugged and hostile scenery of the Alps,… primative horrors of the landscape sublime, and feeling that to introduce even the most insignificant element of human life is to dilute ‘the majestry of its desolation.’ ” [5]

In the image entitled Engadin Gursky presents precise images of mountainscapes in contrast to Turner’s indistinctness expressions. Furthermore, we see the presence of humans, diminished almost to the scale of ants reminding us of nature’s awesome grandeur. What do these two landscapes suggest besides expressing nature’s forces?

Both, I argue, represent interpretations of the sublime and our changing perceptions regarding its nature.

But what is the sublime? The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as that which is ” of such excellence, grandeur, or beauty as to inspire great admiration or awe.” Discussions of the sublime which of late have re-emerged after a haitus, were intensely debated during the first part of the eighteenth century, particularly in England. Edmund Burke’s work Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful was one of the most influential writings on the subject. For Burke, the sublime was, in contrast to the beautiful (usually associated with a

Stormy Mountain heights

Lenk im Simmental

pleasurable experience), a heightened state of awareness that is confronted with the presence of fear, even terror. ” Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is an source of the sublime.” [6] Consequently it has an immense affect on our emotion evoking self-perservation and a sense of our own mortality.

2

Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps 1812

J.M.W.Turner

In his treatise Burke discussed several basic attributes regarding the sublime. These included among others vastness, infinity, magnificence, obscurity, and of course terror and pain. We can observe many of these in the works of Turner as well as Gursky. For Turner, the notion of magnificence, infinity, obscurity as well as terror as they appear in nature and its forces – wind, rain, storms, etc. can be seen in such works as Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps. Here delineations of the mountainscape become a blur of battered fragments in which the landscape disintegrates. Furthermore the obscurity that Turner elucidates suggests for Wilton, an indistinctness: “Here indistinctness is the essence of the sublime, the essence indeed of realism.” [7]

OftenpaB 1993 Andreas Gursky Turner Collection 1995 Andreas Gursky

In observing Gursky’s photographic essays many of the basic attributes that Burke discussed in his treatise are also present. Vastness, and infinity are found not only in Engadine but also Glacier d’Aletsch, S.t.I, and OftenpaB. Curiously he even pays homage to Turner in Turner Collection. But his works also raise new questions regarding the meaning of a sublime that is emersed in a redefined nature, technologically driven and part of a global economy.

Burke’s writings, together with those of John Locke and others, represented for Immanuel Kant a position that engendered the notion of empiricism and rationalism. Briefly, what he was suggesting was twofold: the dynamic sublime extending Burke’s notions of vastness, magnitude, etc. and the mathematical sublime – in particular, phenomena in nature that are at some point measureable. Therefore the notion of the infinite in the sublime ultimately is an idea, not the object’s quality. Hence upon observing the immensity of the experience, the mind overcomes

3

and transcends such fears, conceiving of something larger and more powerful than the thing itself. Thus from awe emerges a heightened awareness through reason of the mind that comprises the sublime. [8]

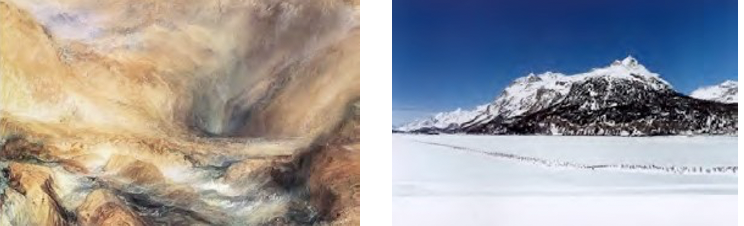

Hoover Dam

When this notion of reason is extended, the relationship between the object… nature itself, and humankind, through the ingenuity of the mind, is completely transformed in the following century, philosophically as well as physically. What Leo Marx called the “rhetoric of the technological sublime” [9] suggests a shift not only in the definition of what nature is, but humankinds’ relationship to it. The emergence of the railroad, electricity, dams (and other impacts on the landscape) as well as skyscrapers, and eventually, the atomic bomb and the computer/internet age suggests that rather than man responding to nature’s forces, he has created a new nature.

Furthermore, rather than Turner’s use of the notion of infinity, nature is now sublimated. As Gilbert-Rolfe observes: “The limitlessness once found in nature gives way, in technology, to a limitlessness produced out of an idea which is not interested in being an idea of nature, but one which replaces the idea of nature.”

This revised definition of limitlessness has been observed by Alicia Imperiale. In her book New Flatness she observes the notion of slippery surfaces. In it she discusses a shift from a focus on ‘depth’ to that of ‘surface.’ She states: “In the context of architecture, the issue of ‘surface’ is a recurring one… We see it most recently in the discussions over the aesthetics of the computer screen and other forms of digital image projection. In its very nature a surface is in an unstable condition. For where are its boundaries? What is its status?” [10]

4

NASDAQ Times Square NYC

Such boundaryless conditions permeate the present world culture. The surface screen as a conveyor of information is about change. The Nasdaq screen in Times Square represents one iteration of a newly emerging information wall. Here however, information is only temporary – fleeting bits of 0’s and 1’s on the computer screen. Its relevancy is subverted by its very nature – to become out-of-date once it is consumed. Only through continuous change can information – and the surface screen survive, reinforcing capitalism’s consumption requirements. Thus, while the screen itself is finite it’s information is openended and thus infinite, harboring both the potential for pleasure as well as pain.

Returning to the work of Gursky the notion of the limitlessness of culture and the sublime now becomes, like the surface screen in Times Square, a series of fleeting moments, frozen in time and on film. His work expressed through digitized ( and manipulated ) imagery defines a globalized technology, and a redefined nature…. often hidden from view, yet acting upon our senses much as the terrors of nature once did through the works of Turner. But we’re not immediately aware of them. The uneasiness with which we view his works suggests

Paris, Montparnasse 1993 Andreas Gursky

that something else is at work. We can readily observe the infinity aspects, what Burke refered to as ” the artificial infinite” [11].. a repetitive sequence of identical parts becoming visible in Paris, Montparnasse where an apartment building seems to extend to infinity, except for the limit of the photographic edge. Likewise, in Hong Kong, Stock Exchange while we observe repetitive

Hong Kong, Stock Exchange 1994 Andreas Gursky

5

elements, this time human beings, now they are engaged in the exchange of monies that do not even appear in the image. The invisible actualities of finance remain concealed in what Alix Ohlin calls ” the nature of money in our time.” [12]

What this suggests and that technology has provided is an emerging virtual world of rapidly changing images that form an ever expanding fragmentation of multiple experiences that, according to Georg Simmel were ” the intensification of the emotional life due to the swift and continuous shift of external and internal stimuli.” Consequently,

” the reaction of the metropolitan person… is moved to a sphere of mental activity which is least sensitive and which is furthest removed from the depths of the personality.” [13] For Simmel this resultant activity resided in the notion of the blasé person.

How does contemporary humankind address this distancing? As Susan Yelavich observes: ” …the dematerialization… as a consequence of electronic digital technolgies… support(s) the idea that our external reality is no longer entirely legible. Perhaps that is why we are more concerned with the fusion of internal and external realities. Increasingly there is a call for the recognition of the presentness of history, and by extension, for the presentness of the spiritual dimension of existence.” [14][15]

Silence as Sublime

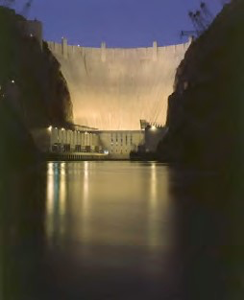

Kino Eye 1929 Dziga Vertov

From a phenomenological perspective a return to the body and its sensorial attributes makes us aware of our own presence and subsequently, the possibility of larger spiritual aspects in providing an alternative to the impacts of technology. In his commentary ” The Eyes of the Skin “

Juhanni Pallasmaa observes recent history (the 1600’s and on) evidences that humankind has 15 observed the world primarily through sight – ” the hegemony of the eye.” . Furthermore the notion of ‘contrived depthlessness’ was used by Fredric Jameson in commenting on the contemporary cultural condition and ” its fixation with appearances, surfaces and instant impacts that have no sustaining power over time.” 16

6

Therefore a sensory balance is needed in which the other senses inform and extend the human experience. I would like to focus on one such sense – sound and in particular its opposite, silence, as the basis for establishing an alternative condition to the technological sublime.

But what is silence? The Oxford English Dictionary states simply that it is the absence of sound and/or the fact or state of abstaining from speech. For Bernard Dauenhauer, however, “Silence is not merely linked with some active human performance. It itself is an active performance.”[16] Furthermore, for Connah this suggests the need for what he calls an “Archive of Silence.”[17] The question then becomes what comprises this archive ? Is it silence as a retreat, refuge, a respite…. or a resistance? On one hand we might acknowledge silence as a respite, a holding back, a retreat out of fear of the present world culture – a form of abdication. On the other hand the notion of a critical resistance suggests an alternative strategy with which to address the zeitgeist. Here we engage in the spatial world of silence, and its multiple readings and meanings.

Kenneth Frampton in an essay on critical regionalism comments on the work of the Japanese architect Tadao Ando. Ando’s use of “microscopic intensity” [18] Frampton observes, resists the urban chaos ( the present dematerialization phenomena) by delineating space that is physically and psychologically isolated in opposition to the vagueness and irrelativity of that environment. This is evidenced in Ando’s work comprising a variety of building typologies including sacred spaces. One such space, The Church of the Light elucidates these issues through the significance of light, shadow, and in particular, the notion of silence. I should like to comment on this in greater depth.

Drawings: The Church of the Light1989 Tadao Ando, Architect

The church is modest in scale – approximately 113 square meters or about the same size of a small house. It consists of a series of smooth concrete walls enclosing the sanctuary. Within this ‘purified space’ Ando provides an order connecting lives of the inhabitants. This order – shintai, meaning union of body and spirit represents a harmony of body experiencing the architectural space. To achieve this Ando provides at the ceremonial terminus of the chapel a concrete wall within which a void in the form of a cross of light appears. This allows light to penetate the darkness within. More significantly the void suggests in Japanese culture, a deeper meaning.. ” In Zen, and Zen art, ‘being’ is considered to be the self-unfolding of the unformed ‘Nothing’ or ‘God’. In particular, the function of the beautiful is to spark an epiphany of the absolute and formless void which is God. True emptiness is the state of zero. This is expressed by the

7

equation zero equals infinity, and vice-versa. Accordingly, emptiness is not literally a lack of content or passivity.” [19] This very much reinforces Dauenhauer’s comments regarding silence… that it contains more than merely an absence – it has it’s own qualities.

Sanctuary; The Church of the Light

The space, stark contrasts between dark and the light of the symbol provides silence and it is at that ” intersection of light and silence we become aware of ‘nothingness’, a void at the heart of things.” 21 Here elements of finitude and temporality elucidate limitlessness and eternity, leading to the sensation of the sublime. As Ando noted ” the brilliance of a shaft of light, penetrating the profound silence of that darkness, amounted to an evocation of the sublime.” [20] This notion of limitlessness returns us back to Kant and his own definitions vis a vis the mathematical sublime. Does this mean a kind of Déjà vu… a return to a pre-industrial world view, albeit a measureable one? On the contrary, for Ando it is that very resistance to the dematerialization aspects of contemporary culture, as a consequence of industrialization and technology as reflected in his own notion of limitlessness that sustains silence as a condition of the sublime.

A Technological Sublime or Silence as Sublime?

Nagano Prefectural Shinano Art Museum 1989 Yoshio Taniguchi, Architect

8

The issue of the contemporary sublime presents seemingly contradictory conditions, and one that requires some kind of response. On one hand we have the notion of a technological sublime with its inherent emphasis on the external world, now evolving further into a virtual world of computerized intelligence systems. Consequently, the limitlessness and vastness aspects as once enunciated by Burke and Kant ( in response to nature) have been completely redefined and to some extent become unfathonable. On the other hand the human condition requires that we live in a world also inhabited by the body, the senses, and even if in retreat, or as a resistance, we need the presence of absence, the notion of silence in order to sustain ourselves. As a balance against the cacophonous world around us, silence provides a meaningful response. Consequently, how do we reconcile these two conditions?

Threshold III Jake Baddeley

In a paper that I and my colleague presented at a conference a few years ago we observed that one of the arguments that has been made regarding postmodernism ( the contemporary zeitgeist) is that it is effectively schizophrenic… meaning living in two completely different realities at once. We argued in our paper that it is not an illness, but rather a natural quality of our time.[21] What this suggests within the framework of this paper is that two possibilites might exist in reconciling both the technological and silence as sublime conditions.

The first is the possibility of observing the two as a hybrid. Much like two parents providing a child, it is in fact a fusion. What this provides, however, is a kind of blurring effect that no longer distinguishes between the two conditions. While this might appear to be quite appealing in resolving the schizophrenia of modern culture, it does not address the distinct aspects of the two conditions that still seems to prevail.

9

TV Buddha 1974 Nam June Paik

The second is the possibility of the two conditions remaining as distinct entities in a state of symbiosis. In this state an oscillation occurs between the two conditions.The Japanese architect Kurokawa observes what he calls ‘intermediate space’ as a place where differing conditions, culturally, economically, spatially can co-exist. For him it is about moving back and forth, a kind of oscillation between two realms and a crossing of thresholds – liminal territories, that comprise the notion of symbiosis. Even in his own house he articulates the need to move between two rooms: the tea room ( the room of silence and ceremony) and the computer room ( the room of virtual reality).[22]

I would like to argue that the notion of symbiosis provides a more meaningful response to the question. Implying a relationship of mutual need between different parties in which there still could be competition, opposition, and struggle as long as there are common elements, for Kurokawa “the concept of symbiosis is basically a dynamic pluralism. It does not seek to reconcile binomial opposites… but instead implies situations that are ambiguous, and plagued with multivalences and contradictions.” 25 These two conditions then… a technological sublime vs. silence as sublime are not resolved through an ‘either/or’ condition but rather one that embodies a ‘both/and’ response. They are therefore, mutually dependent upon each other. Such is the dilemma of our time. Besides, as Gilbert-Rolfe implied, if gravity still exists, so too must the sublime, albeit, quite transformed.

Bibliography

Ando, Tadao, “The Eternal Within the Moment,” Dal Co, F (ed), Tadao Ando: Complete Works, Phaidon, London, 1995

Bermudez, Julio and Hermanson, Robert, “Tectonics After Virtuality: Re-turning to the Body,” in Proceedings of ACSA International Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, Royal Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture, 1996

Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful, Penguin Books Ltd., London, 1998

Connah, Roger, ” Sometimes and Always, with Mixed Feelings: Untimely Notes on a Culture of Silence,” in

Malcolm Quantrill, Bruce Webb, editors, The Culture of Silence: Architecture’s Fifth Dimension, CASA, 1998

Dauenhauer, Bernard P., Silence: The Phenomenon and Its Ontological Significance, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, 1980

Drew, P., Church on the Water, Church of the Light Tadao Ando, Phaidon Press Ltd. London, 1996

10

Frampton, Kenneth, “The Japanese New Wave,” New Wave of Japanese Architecture,: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, New York, 1978

Fyfe, W.H. and Russell, Donald, Longinus: On the Sublime, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1995

Gilbert-Rolfe, Jeremy, Beauty and the Contemporary Sublime, Allworth Press, New York, 1999

Imperiale, Alicia, New Flatness: Surface Tension in Digital Architecture, Basel: Birkäuser, Basel, 2000

Kant, Immanuel, Critique of Judgment, Trans. J.H. Bernard. Macmillan, London, 1951

Marx, Leo, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, Oxford University Press, New York, 1964

Ohlin, Alix, “Andreas Gursky and the Contemporary Sublime,” Art Journal, Winter 2002

Pallasmaa, Juhani, “The Eyes of the Skin,” Polemics, Academy Editions, London, 1996

Simmel, Georg, “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” Rethinking Architecture, Routledge,

New York, 1997

Wilton, Andrew, Turner and the Sublime, British Museum Publications Ltd., London, 1980

Yelavich, Susan, “Setting the Stage for the Third Millennium,” in Susan Yelavich, ed., The Edge of the Millennium, Whitney Library of Design, New York, 1993

Illustration Sources

The Pass of Faido http://www.fineart-china.com/open_img.php?bh=53399

Engadin

Syring, Marie Luise, editor, Andreas Gursky: Photographs from 1984 to the Present, Schirmer/Mosel, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1998, p. 75

Stormy Mountain http://commondatastorage.googleapis.com/static.panoramio.com/photos/original/14861713.jpg

Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps http://www.sinoutopia.org/resources/20090613.Turner.From.The.Tate.Collection/jmwt_mma_03.jpg

Ofenpaß

Syring, Marie Luise, editor, Andreas Gursky: Photographs from 1984 to the Present, Schirmer/Mosel, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1998, p. 121

Turner Collection

Syring, Marie Luise, editor, Andreas Gursky: Photographs from 1984 to the Present, Schirmer/Mosel, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1998, p. 131

Hoover Dam:

http://www.usbr.gov/lc/hooverdam/images/C45-20485-L.jpg

NASDAQ Times Square NYC

http://www.coderetard.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/05/marketsite5.jpg

11

Paris, Montparnasse

Syring, Marie Luise, editor, Andreas Gursky: Photographs from 1984 to the Present, Schirmer/Mosel, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1998, p. 46

Hong Kong Stock Exchange

Syring, Marie Luise, editor, Andreas Gursky: Photographs from 1984 to the Present, Schirmer/Mosel, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1998, p. 58

Kino Eye http://blog.art21.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/kino-glaz.jpg

Drawings: The Church of Light http://www.tokinowasuremono.com/shop/w/w020.jpg

Sanctuary: The Church of Light

www.tokinowasuremono.com/shop/w/w020.jpg

Nagano Prefectural: Shinano Art Museum

Photos: Robert Hermanson

Threshold III http://www.absolutearts.com/cgi-bin/portfolio/art/your- art.cgi?login=jbaddeley&title=Threshold_III1156448273t.jpg

TV Buddha http://falsedawn.blogspot.com/tvbudhhapaiksmall.jpg

[1] Gilbert-Rolfe, Jeremy, Beauty and the Contemporary Sublime, Allworth Press, New York,1999, front fold

[2] Ibid

[3] Connah, Roger, ” Sometimes and Always, with Mixed Feelings: Untimely Notes on a Culture of Silence,” in Malcolm Quantrill, Bruce Webb, editors, The Culture of Silence: Architecture’s Fifth Dimension, CASA, 1998, p. 5-6

[4] The term is open to several interpretations. The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as”the phenomena of the physical world collectively, including plants, animals, the landscape, and other features and products of the earth, as opposed to humans or human creations.” For Leo Marx however, the idea of nature was what he called “one of the fundamental American ideas” that was profoundly transformed as the nation moved from an agrarian society to that of a technologically driven one. No longer a pristine environment, nature was now transformed into humankind’s own making. See Marx, Leo, “The idea of nature in America,” in Daedalus, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2008, pp-8-21

[5] Wilton, Andrew, Turner and the Sublime, British Museum Publications Ltd., London, 1980, p. 80

[6] Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful, Penguin Books Ltd., London, 1998, p. 86

[7] Wilton, p. 72

[8] Kant, Immanuel, Critique of Judgment, Trans. J.H. Bernard. Macmillan, London,1951.

[9] Marx, Leo, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America, Oxford University Press, New York, 1964

[10] Imperiale, Alicia, New Flatness: Surface Tension in Digital Architecture, Basel: Birkäuser, Basel, 2000, p.5

[11] Burke, p.168

[12] Ohlin,Alix, “Andreas Gursky and the Contemporary Sublime,” Art Journal, Winter 2002, p. 25

[13] Simmel, Georg, “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” Rethinking Architecture, Routledge, New York, 1997

[14] Yelavich,Susan, “Setting the Stage for the Third Millennium,” in Susan Yelavich, ed., The Edge of the

Millennium, New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1993, p 11-14

[15] Pallasmaa, Juhani, “The Eyes of the Skin,” Polemics, Academy Editions, London, 1996 16 Ibid, p. 19

[16] Dauenhauer, Bernard P., Silence: The Phenomenon and Its Ontological Significance, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, 1980, p.4

[17] Connah, op cit

[18] Frampton, Kenneth, “The Japanese New Wave,” New Wave of Japanese Architecture, The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies,New York, 1978, p.2

[19] Drew, P., Church on the Water, Church of the Light Tadao Ando, Phaidon Press Ltd. London, 1996, p.8 21 Ibid

[20] Ando, Tadao, “The Eternal Within the Moment,” Dal Co, F (ed), Tadao Ando: Complete Works, Phaidon, London, 1995

[21] Bermudez, Julio and Hermanson, Robert, “Tectonics After Virtuality: Re-turning to the Body,” in Proceedings of ACSA International Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, Royal Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture, 1996 p 66–71

[22] Kurokawa, Kisho, The Philosophy of Symbiosis, Academy Editions, London, 1994 25 Ibid