Brandon R. Ro

Architect and Independent Researcher

brandon.r.ro@gmail.com

Introduction

“Space, like language, is socially constructed; and like the syntax of language, the spatial arrangements of our buildings and communities reflect and reinforce the nature of gender, race, and class relations in society,”[1] argues Leslie Weisman. At times political policies or sociocultural norms are such that the status-quo is accustomed to spatially separating female and male activities. For example, late-nineteenth century Victorian concerns about morality, modesty, and privacy were reflected in the creation of separate dressing rooms, bathing facilities, and restrooms for each sex.[2] One social construct that is sometimes overlooked in the study of sacred architecture involves how the binary symbolism of gender (i.e., feminine and masculine) is mapped or “encoded in built form.”[3] What are the meanings associated with placing women or a bride on the left (north) side of a church and the men or groom opposite on the right (south)?

Defining Gendered Sacred Space

One of the ways that the social construct of gender manifests itself in sacred architecture is through clearly demarcated spatial hierarchies, seating arrangements, iconographic configurations, and liturgical requirements. Referred to by Tammy Gaber as “gendered spaces,” organizing worshippers along gender lines can be reinforced via “architectural devices such as walls, balconies, separate rooms, separate doors,” and even “signage directing where each gender is allowed access.”[4] This suggests that the profane and secular socioeconomic constructs of society are mirrored in the sacred and holy spaces that religious traditions have built over the ages. One might wonder if a gendered space, therefore, can actually still be considered sacred. Some commentators contest that most (if not all) “sacred space is socially constructed.”[5] Others argue that sacred space is “qualitatively different” than that found in society, since it is where the “profane world is transcended.”[6]

Frank Lloyd Wright’s concept of continuity could prove insightful when considering the sacredness of gendered space. “Instead of two things, one thing…Let walls, ceilings, floors become part of each other, flowing into one another.”7 This may at first suggest a proposal towards partition-less homogeneous space without gender divisions; yet, Wright was not necessarily advocating for the landscape and building to completely lose their individuality, per se, where differentiation between the two would be lost. Instead, it appears he was suggesting that the two distinct heterogeneous objects be viewed as a complementary whole. Leon Battista Alberti, likewise, described beauty as architecture that maintains harmony and balance between all the parts.8 Indeed, the theme of the symposium explores the “unifying nature of continuity” by encouraging an appreciation of “variety, transformation, and difference” – albeit through spatial, social, and spiritual connections. For Mary Douglas, “Holiness means keeping distinct the categories of creation.”9 Perhaps when viewing gendered spaces in this light, male and female spaces can transcend the profane world and retain their holiness by transforming two things into one spiritual union. As St. Paul argued long ago, “There is neither… male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28); for “neither is the man without the woman, neither the woman without the man, in the Lord” (1 Corinthians 11:11). With this backdrop in mind, this paper seeks to explore the social construct of gendered sacred space for the Christian tradition and its multivalent perspectives that have lasted nearly 1,700 years. In particular, the paper advances a claim to improve the impoverished, neglected, and underappreciated understanding that gender separation in sacred architecture was not a demeaning practice but one that celebrated the complimentary nature of men and women.

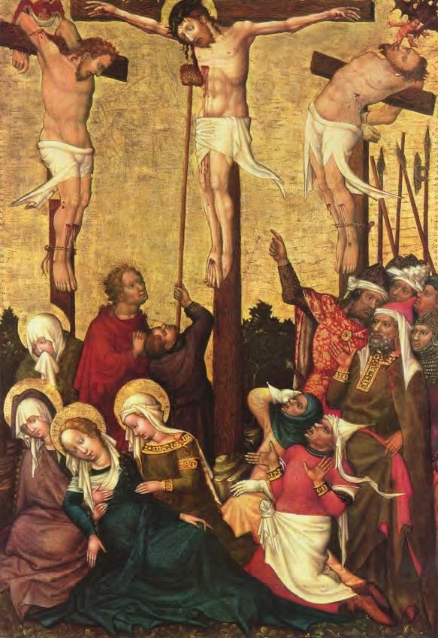

Figure 1. In the Crucifixion by Hans von Tübingen, (c.1430) the good thief and holy women are on Jesus’ right hand while the evil thief and accusers are to his left (public domain). Image courtesy of The Yorck Project: 10,000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002.

Method + Scope

Hermeneutics is the method for identifying, comparing, and assessing the ritual occasions and various messages tied to gendered sacred space within Christianity in this paper. Hermeneutics is a process for reading, understanding, interpreting, and handling “texts.” For this study, religious “texts” are defined as liturgical or scriptural canon, ritual practices, religious art, spiritual experiences, and sacred spaces.[7] Since hermeneutics “produces habits of respect for, and more sympathetic understanding of, views and arguments that at first seem alien or unacceptable,” this methodology can be viewed as an effort “to establish bridges between opposing viewpoints.”[8]

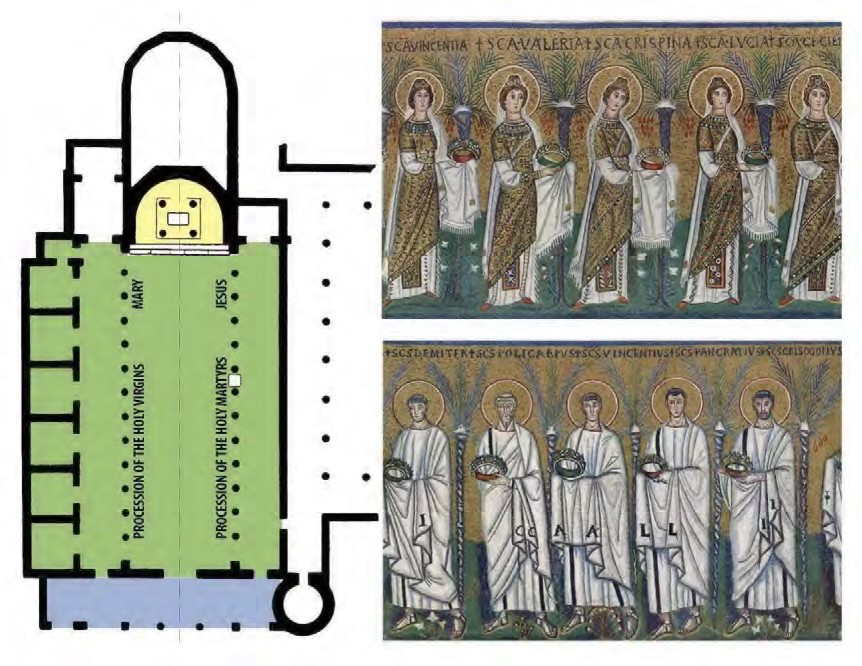

Figure 2. The Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy embodies gender spatial symbolism with connections to Jesus as the new Adam with a procession of male saints on the right (bottom) and Mary as the new Eve with another procession of female saints on the left (top). Mosaic artwork by Master of Sant’Apollinare around 526 AD (public domain). Images courtesy of The Yorck Project: 10,000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. Conjectural floor plan by author.

The multivalent messages associated with ritual-architectural configurations exhibiting so-called “gendered space” categorically fall under Lindsay Jones’ “politics” priority for interpreting sacred architecture. Typically gendered spaces will appear to either perpetuate and reinforce socioeconomic hierarchies or challenge and suspend them.[9] As discussed above, however, this paper seeks to go beyond the obvious mapping of gendered space and its spatial hierarchy. It seeks to understand “which social distinctions, particularly along gender lines, are fully integrated into complex homologized systems of mythological, cosmological, and spatial correlations” among the Christian tradition.[10] As its scope, this paper explores several manifestations of gendered space from different time periods in Christian architectural history.

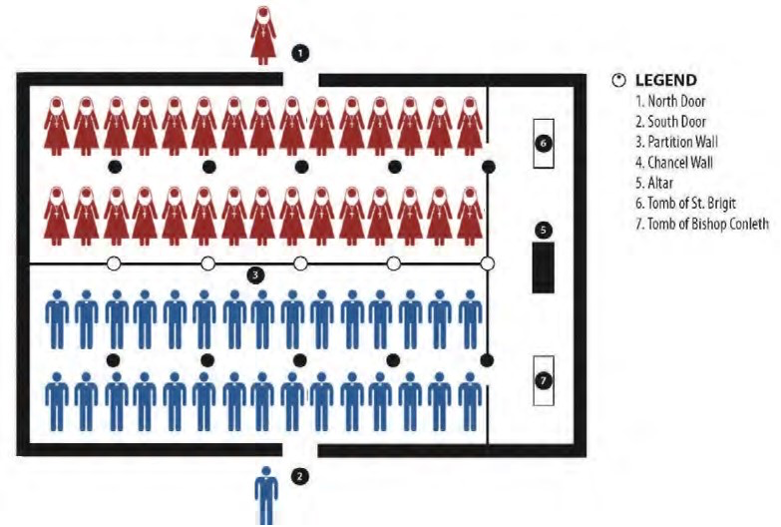

Figure 3. Conjectural floorplan of the Shrine of St. Brigit in Kildare, Ireland as described by Cogitosus in the 7th century. The plan illustrates how Catholic gendered space used separate entrances for each gender as well as a partition wall down the center of the church to separate the sexes. Image redrawn by author after Roberta Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Religious Women (New York: Routledge, 2005), 135.

Balancing Perspectives via Pious Skepticism

Several scholars approaching gendered space from a feminist lens have placed special emphasis on the discriminatory and misogynist messages derived from patriarchal dominion. Analytical approaches from feminism, however, do not always provide adequate historical interpretations. Indeed, all scholars must be careful about forcing a twenty-first century perspective on persons of the historical past. “If we look carefully at what medieval people wrote, how they worshipped, and how they behaved,” argues Caroline Bynum, “their notions about gender seem vastly more complex than recent attention to the misogynist tradition would suggest.”14 Thus, the sociospatial mapping of gender onto Christian sacred spaces and the demystification of its messages can at best only provide partial glimpses and remnants of the past.

Consequently, in an effort to avoid blind scholarship and engage in the rigorous historical investigation and “hermeneutical calisthenics”[11] needed for assessing such neglected messages, I propose a reassessment to some of the existing academic interpretations associated with

Christian gendered sacred space. This requires approaching the topic with what C.W. Westfall calls “pious skepticism”16 or what Lindsay Jones’ refers to as a “skeptical-minded hermeneutic of suspicion.”17 In short, it can be described as a “fundamentally skeptical approach to the inherited tradition while assuming the possibility of some value being found there,” such as insights from an opposing (non status-quo reinforcing) perspective.18

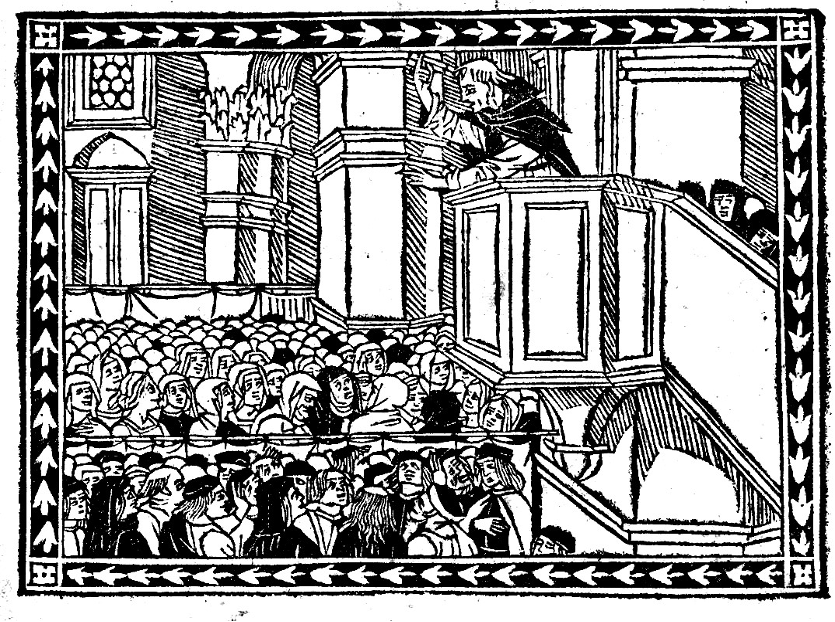

Figure 3. In 1496 gender separation was present during the preaching of Girolamo Savonarola in the Duomo in Florence, Italy. Image source: Woodcut in Compendio di revelatione / dello invtile servo di Iesv Christo frate Hieronymo da Ferrara dellordine de Frati Predicatori (Public Domain).

The Prospectus of Gendered Sacred Space

In the history of Christianity there has been a long tradition of gendering spaces within religious buildings through spatial means that relate back to the body. Each sex typically had its place within the binary order of the church, such as the left or right, north or south, front or back, east or west, upper gallery or main level. The male-female spatial divide has been used to convey a number of messages over time. Some interpreters suggest the practice has denigrated women while others argue that it exalts them as the more pure and noble sex. Most often, the mapping of gender occurred along the longitudinal axis of a church with men on the south and women on the north. When facing an apse oriented to the east, women are typically found on the left side of the altar and men on the right side. As we examine some of the misconceptions of gendered space used by scholars to suggest that it was a demeaning practice towards women, note that many of these interpretations should be reversed since gendered space celebrated the sexes by maintaining a moral order.

Multivalent perspectives about gendered sacred space emerge by examining several examples and case studies that come to us over the course of Christian history. Important for this prospectus is the relationship of how gender is mapped onto the longitudinal axis of Churches. This paper begins by exploring several theological arguments from early Christian church patriarchs and fathers who explain that the purpose of separating the sexes was to maintain moral order and keep space sacred. Two case studies from the sixth and seventh centuries are examined to discern how gendered spatial divisions were developed and implemented. After several centuries of practicing gendered sacred space, new interpretations emerged during the latter part of the Middle Ages describing men as the stronger sex since they were ready for danger and greater temptations than women. Those interpretations were quickly turned on their head, however, as the Renaissance and Reformation liturgical art and architecture trends emerged on the scene. Examples from several important Italian religious structures in Siena, Milan, Rome, and Florence are analyzed. It is at this point that the paper explores how gender symbolism was reversed when viewed from God’s perspective at the head of the altar. Since the Virgin Mary and women were depicted on his blessed right hand, they were given a privileged, honored, and even sacred position within the church.

Conclusion

Value is derived by the varied perspectives gained through hermeneutical exercises since they paint a broader (often under-appreciated) historical interpretation. These arise from discussing several theological arguments for separating the sexes during worship and how their implementation occurred throughout Christian history. The conclusion of this paper, therefore, is found in the perspectives on the continuity of gendered space within the Christian tradition. The examples in this paper demonstrate that gendered sacred space was not always a demeaning practice towards women. Instead, many of the theological arguments suggest that it was a practice that celebrated the complementary nature of man and woman, the masculine and feminine. The purpose of separating the sexes was focused on maintaining holiness and order versus inflicting oppressive injustice and discrimination. More often than not women were viewed as the greater sex in terms of moral strength, piety, and divine attributes. In fact, elimination of sexual distractions and desire was the objective of such physical divisions so pilgrims could enhance their contemplative ritual-experience and focus on the divine. From the layperson’s vantage point women on the left side of the church may have suggested inferiority, but from God’s perspective at the head of the altar they were located at his blessed right hand. It is men who are located on the condemning left hand of God. The hermeneutical messages towards women are more complex than some scholars have supposed. As such, gendered separation in sacred architecture was not always a demeaning practice but one that celebrated the complimentary spiritual nature of men and women.

References

Agnellus, Abbot. The Book of Pontiffs of the Church of Ravenna. Edited by Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis.

Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2004.

Aston, Margaret. “Segregation in Church.” Studies in Church History 27 (1990): 237-94.

Bingham, Joseph. Origines Ecclesiasticae: Or the Antiquities of the Christian Church. Edited by Richard Bingham. 9 vols. London: William Straker, 1843.

The Book of Common Prayer, 1549. Commonly Called the First Book of Edward Vi to Which Is Added the Ordinal of 1549, and the Order of Holy Communion, 1549. New York: Church Kalendar Press, 1881.

Bynum, Caroline Walker. Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion. New York: Zone Books, 1991.

Chrysostom, John. Homilies of S. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, on the Gospel of St.

Matthew, Part 3, Hom. 59-90. London: Oxford, John Henry Parker, 1851.

Cooper, James, and Arthur John Maclean, eds. The Testament of Our Lord (Testamentum Domini), Translated into English from the Syriac with Introduction and Notes. London: T. & T. Clark, Edinburgh, 1902.

Davies, Oliver, and Thomas O’Loughlin. Celtic Spirituality. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1999.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Durandus, William. The Symbolism of Churches and Church Ornaments: A Translation of the First Book of the Rationale Divinorum Officiorum Written by William Durandus. Edited by John M. Neale and Benjamin Webb. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1893.

Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane; the Nature of Religion. New York: Harcourt, 1987.

Friedland, Roger, and Richard D. Hecht. “The Politics of Holy Place: Jerusalem Temple Mount/Al-Haram aSharif.” In Sacred Places and Profane Spaces: Essays in the Geographics of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, edited by Jamie Scott and Paul Simpson-Housley, 21-62. New York: Greenwood Press, 1991.

Gaber, Tammy. “Gendered Mosque Spaces.” Faith & Form 48, no. 1 (2015).

Gilchrist, Roberta. Gender and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Religious Women. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Howell, A.G. Ferrers S. Bernardino of Siena. London: Methuen, 1913.

“Inside the Basilica.” The Papal Basilica Santa Maria Maggiore, Vatican, Accessed 19 September 2017, http://www.vatican.va/various/basiliche/sm_maggiore/en/storia/interno.htm.

Jones, Lindsay. “Architectural Catalysts to Contemplation.” In Transcending Architecture: Contemporary Views of Sacred Space, edited by Julio Bermudez, 170-207. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2015.

———. The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture: Experience, Interpretation, Comparison. 2 vols, Religions of the World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Lang, U. M. Turning Towards the Lord: Orientation in Liturgical Prayer. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2004. McNamara, Denis R. Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy. Chicago: Hillenbrand Books, 2009.

Origo, Iris. The World of San Bernardino. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1962.

Roberts, Alexander, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, eds. The Ante-Nicene Fathers: Translations of the Writings of the Fathers Down to A.D. 325. 10 vols. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature, 1885.

Schaff, Philip, and Henry Wace, eds. A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church: Second Series. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1904.

Schleif, Corine. “Men on the Right—Women on the Left: (a)Symmetrical Spaces and Gendered Places.” In Women’s Space: Patronage, Place, and Gender in the Medieval Church, edited by Virginia Chieffo Raguin and Sarah Stanbury, 207-49. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2005.

Thiselton, Anthony C. Hermeneutics: An Introduction. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans, 2009.

Twombly, Robert C. Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and His Architecture. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1987.

Voelker, Evelyn Carole. Charles Borromeo’s Instructiones Fabricae Et Supellectilis Ecclesiasticae, 1577:

Book 1 and Book 2, a Translation with Commentary and Analysis. Clemson, SC: Author, 2008.

Wace, Henry, and Philip Schaff, eds. A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church: Second Series. Vol. 7. London: James Parker and Company, 1894.

Weisman, Leslie. Discrimination by Design: A Feminist Critique of the Man-Made Environment. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

Westfall, Carroll William. “Architecture and Democracy, Democracy and Architecture.” In Democracy and the Arts, edited by Arthur M. Melzer, Jerry Weinberger and M. Richard Zinman, 73-91. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999.

White, James F. Roman Catholic Worship: Trent to Today. 2nd ed. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2003.

Wightman, G. J. Sacred Spaces: Religious Architecture in the Ancient World, Ancient near Eastern Studies. Supplement 22. Louvain, Belgium: Peeters, 2007.

[1] Leslie Weisman, Discrimination by Design: A Feminist Critique of the Man-Made Environment (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 2.

[2] For a brief history of sex-separation in restrooms in the United States and their associated building codes tied to upholding social morality, see Terry S. Kogan, “Sex-Separation in Public Restrooms: Law, Architecture, and Gender,” Michigan Journal of Gender and Law 14, no. 1 (2007); ———, “How Did Public

Bathrooms Get to Be Separated by Sex in the First Place?,” Conversation(26 May 2016), Accessed 13 September 2018, https://theconversation.com/how-did-public-bathrooms-get-to-be-separated-by-sex-in-thefirst-place-59575; ———, “Public Restrooms and the Distorting of Transgender Identity, 95 N.C. L. Rev. 1205 (2017).” North Carolina Law Review 95(2017): 1212-21.

[3] G. J. Wightman, Sacred Spaces: Religious Architecture in the Ancient World, Ancient near Eastern Studies. Supplement 22 (Louvain, Belgium: Peeters, 2007), 914.

[4] Tammy Gaber, “Gendered Mosque Spaces,” Faith & Form 48, no. 1 (2015).

[5] Roger Friedland and Richard D. Hecht, “The Politics of Holy Place: Jerusalem Temple Mount/Al-Haram a-

Sharif,” in Sacred Places and Profane Spaces: Essays in the Geographics of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, ed. Jamie Scott and Paul Simpson-Housley (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991), 55. The authors also argue that historians of religion are the culprits who have stripped sacred space of “politics and real history” by focusing solely on its “metaphors or aesthetic indices” (p.25).

[6] Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane; the Nature of Religion (New York: Harcourt, 1987), 25-26.

7 Robert C. Twombly, Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and His Architecture (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1987), 315. 8

Leon Battista Alberti, The Ten Books of Architecture: The 1755 Leoni Edition (New York: Dover, 1986), bk VI, ch II, p.113. 9

Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (New York: Routledge, 2013), 54.

[7] For more on how architecture can be viewed and read as a text, see Lindsay Jones, The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture: Experience, Interpretation, Comparison, 2 vols., Religions of the World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 1:121-33.

[8] Anthony C. Thiselton, Hermeneutics: An Introduction (Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans, 2009), 5-6. Cf. Francis X. Clooney, Comparative Theology: Deep Learning across Religious Borders (Oxford: WileyBlackwell, 2010), 162.

[9] Jones, The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture, 2:133-41, 308-10.

[10] Ibid., 2:134-35. 14

Caroline Walker Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion (New York: Zone Books, 1991), 152.

[11] A subtitle of his second volume for interpreting sacred architecture, Jones uses this phrase to introduce the process of synchronic, cross-cultural comparison. See Jones, The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture, 2:1-24.

12 Jones, The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture, 2:133-41, 308-10.

13 Ibid., 2:134-35.

14 Caroline Walker Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion (New York: Zone Books, 1991), 152.

15 A subtitle of his second volume for interpreting sacred architecture, Jones uses this phrase to introduce the process of synchronic, cross-cultural comparison. See Jones, The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture, 2:1-24.

16 Carroll William Westfall, “Architecture and Democracy, Democracy and Architecture,” in Democracy and the Arts, ed. Arthur M. Melzer, Jerry Weinberger, and M. Richard Zinman (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999).

17 Lindsay Jones, “Architectural Catalysts to Contemplation,” in Transcending Architecture: Contemporary Views of Sacred Space, ed. Julio Bermudez (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2015), 205.

18 Denis R. McNamara, Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy (Chicago: Hillenbrand Books, 2009), 201.