Sanda Iliescu

The University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA

iliescu@virginia.edu

I have made drawings, collages, and paintings all my life. I make art in good times and bad. It does not always come easily but it is usually very fulfilling. It is who I am.

One day five years ago, at a time of great personal difficulty, I picked up my pencil and tried to make a drawing. To my horror I could not do it. I was too overwhelmed by grief and self-doubt. I recall sitting for what felt like hours, staring at a blank piece of paper, pencil in hand.

Then, somehow, I found the courage to begin drawing. My hand seemed to move by itself: slowly, it traced the rough, awkward form of a human being crying. The image looked so sad it made me cry, but, as I drew the tears, something opened inside me. Feeling the need to comfort the poor creature, I gave it wings. The human form became an angel.

As I drew, the darkness inside me lifted. Everything around me came to life—not only the paper, pen, and the lines I drew, but also the birds chirping outside my window; the patch of sunshine on the floor; the smell of cooking emanating from the kitchen. All these ordinary things suddenly seemed very special, even miraculous.

I continued to draw angels for the next few days. As I did so, I tried to express my new appreciation for the everyday—to give common objects and places I had ignored before a measure of grace and dignity. Intuitively, I drew my angels in quotidian attitudes and doing simple, ordinary activities. One, for instance, is carrying a tray with ointment jars and medicine bottles. Another has just discovered and is quietly examining a very small snail. One angel is playing a musical instrument while looking ruefully and perhaps enviously at a little bird. With a puzzled expression on his face, another angel is carefully reviewing pages in a three-ring binder.

To this day, I continue to draw angels engaged in such everyday activities. I never show them flying or inhabiting celestial realms. They are always here on earth and doing things we humans do. They are what I might call “secular angels.”

In his 2009 book Encountering the Secular, philosopher J. Heath Atchley draws on sources as diverse as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Gilles Deleuze to explore the spiritual dimensions of secular life.i All too often, he argues, we think of the secular as only an antidote to the presumed irrationality and oppression of religion—or we lament the way the secular has robbed our lives of the meaning that religion once brought. For Atchley, the secular can be much more: it can have an immanent spiritual value.

Atchley proposes that the realms of the secular and the sacred, which we tend to think of as opposites, are not as far from one another as we might think. The borders between them, he argues, are highly porous and ambiguous. He writes:

The rigid separation between these two realms, [the Secular and the Sacred], gets in the way of experiencing an immanent value, a kind tied neither to transcendent reality (e.g., god or an ideal) nor to the satisfaction of the self (e.g., pleasure or knowledge).

This summer, at the suggestion of one of the ACSF 13 readers of this paper, I read Eckhart Tolle’s 1997 book, The Power of Now.ii Although a very different kind of writer than Atchley, Tolle, who is a spiritual writer, also has a vision of a much more porous kind of relationship between the secular and the sacred. In the book, he describes a powerful spiritual experience he underwent.

In 1977, at the age of 29, Tolle awoke in the middle of the night in a state of great depression and anxiety. Significantly, he describes his ordeal in terms of ordinary, quotidian things. He writes:

The silence of the night, the vague outlines of the furniture in the dark room, the distant noise of a passing train—everything felt so alien, so hostile, and so meaningless that it created in me a deep loathing of the world.”

He was seized as well with a deep loathing of himself. He felt he could not “live with himself any longer.”

But the moment he thought about this, he realized this expression implied a splitting of the self into two parts—the “I” and the “himself” with whom the I cannot live. This was wrong, he felt, and this realization led to a transcendent experience. His depression and anxiety vanished. In their place, Tolle experienced a terrifying “void.” He writes:

I was gripped by an intense fear, and my body started to shake. I heard the words “resist nothing,” as if spoken inside my chest. I could feel myself being sucked into a void.

Upon awakening the next morning, Tolle’s world was utterly transformed. He writes:

Everything was fresh and pristine, as if it had just come into existence. I picked up things, a pencil, an empty bottle, marveling at the beauty and aliveness of it all.

There are three parts to Tolle’s spiritual experience: a first state of depression, anxiety, and self- loathing; a second, middle, transcendent state—that mysterious void—that may be interpreted as a contact with some god or divine force “beyond” this world; and a third state of joy, wonder, and love for the simple things of this world.

I have never had a transcendent experience of the kind Tolle describes as a terrifying void. But I am familiar with his first and third transitional states, with the fear and despair, and with the joy and wonder he describes, as well as with the surprisingly important role that common, ordinary objects and places can play at such times. I have come to think of these states of mind as, if not transcendent, then as transitional states, ones that possess a deep spirituality that is difficult to account for in rational or psychological ways.

Like Tolle, I experienced a long period of self-doubt and deep sadness before I drew my first angel. My awareness of special, important things in my life—the people I loved, the books I took pleasure in—completely vanished. All I had left were the prosaic things in the world around me: the kitchen sink, the bedroom dresser, the night-lamp. These ordinary things seemed not only dull, but alien, hostile, and ugly. Also, like Tolle, during my later period of joy and wonder, I became acutely aware of these same prosaic things. This time, however, they were transformed: they became, as Tolle puts it, “alive, fresh, and beautiful.”

The English word “angel” comes from the late Greek “angelos,” which means “messenger,” and which may go back to the Persian “angaros,” or mounted courier. Traditionally, angels act as intermediaries or messengers connecting us with a divine realm. I believe it is possible to interpret the first and third stages of Tolle’s—and my own experiences—as angelic manifestations: as moments when we were touched or visited by angels.

A short while after I drew my first angel, I read a story by American fiction writer Donald Barthelme titled “On Angels.” In it, Barthelme speculates on what might happen to angels in a world that has lost its belief in a divine being. The story opens with this provocative passage:

The death of God left the angels in a strange position. They were overtaken suddenly by a fundamental question. One can attempt to imagine the moment. How did they look at the instant the question invaded them, flooding the angelic consciousness, taking hold with terrifying force? The question was, what are angels?iii

While reading Tolle’s book, I asked myself an analogous question. What happens when there is no contact with the divine—no transcendent and terrifying void that sucks us in? What happens to the other two states which I have called angelic manifestations: the first state of sorrow and profound spiritual depletion and the latter experience of profound joy and love?

Without the existence of a divine being these other states would of course change: they would become, I believe, passages to something that is only suggested or promised, not fulfilled. In a similar way, Donald Barthelme’s angels also change. They suffer doubts, fall into despair, and experience terror. They cry and lament; they experience curiosity and states of adoration; they shout and holler; they philosophize inconclusively on the nature of Chaos. Without God, they gain very human qualities.

Ultimately, Barthelme’s angels consider refusing to be. Toward the end of the story, they wish to die. Barthelme writes:

The most serious because most radical proposal considered by the angels was refusal— they would remove themselves from being, [they would] not be.

Barthelme’s story has a dark humor, but it is also very melancholy. It begins with the death of God and ends with the death of angels. After reading it, I asked myself, what would happen to human beings if we had not only no divinity but also no spiritual experiences—no angels about us? How would we relate to the ordinary, everyday world around us? What would we become?

Without a sense of wonder, joy, and love—and without too our sense of despair and profound sadness—our relationships to ordinary objects would become purely practical (we would use them to achieve our goals), or materialistic (we would value them as possessions and as instruments of power), or careless (we would not value them at all). We would also lose our sense of curiosity and openness to unforeseen possibilities. Perhaps we might also lose our capacity to empathize and even to love.

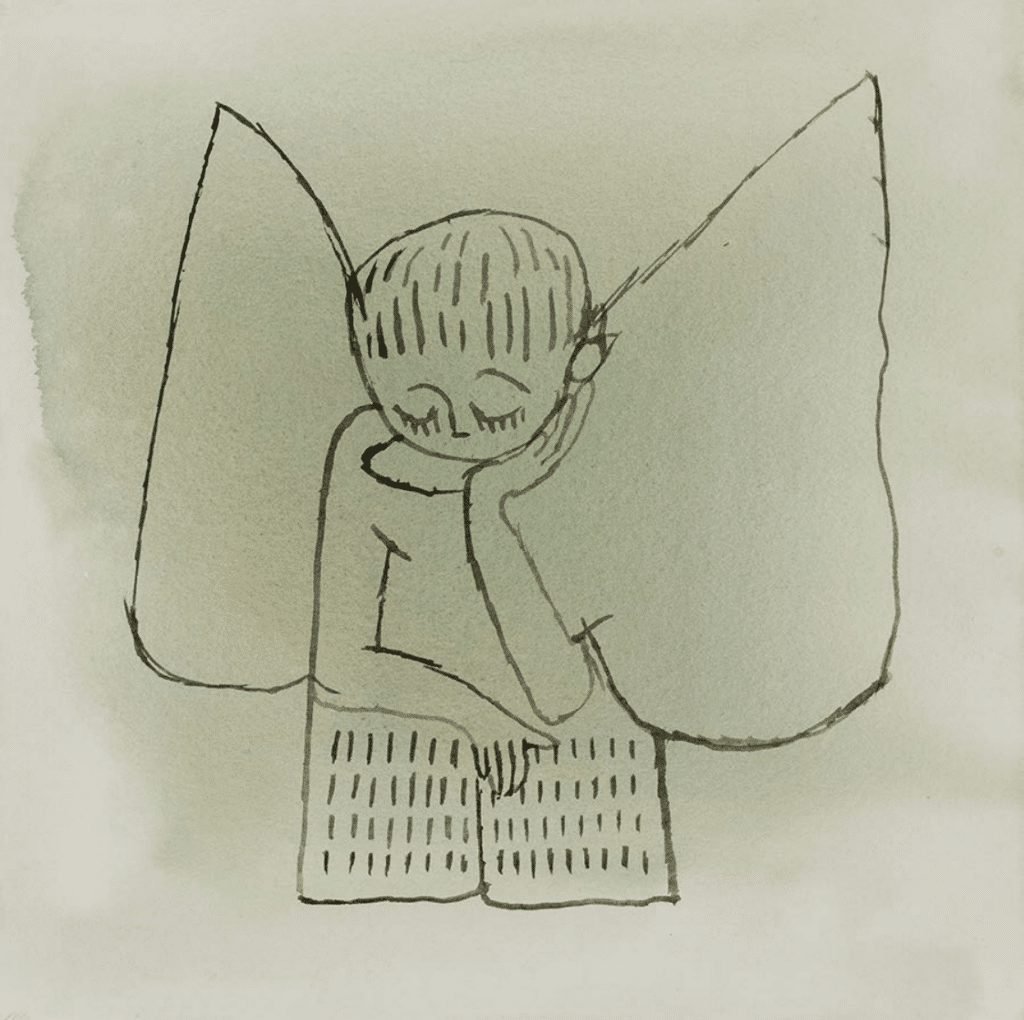

Angel Reading

Sanda Iliescu

Watercolor on Paper, 2019

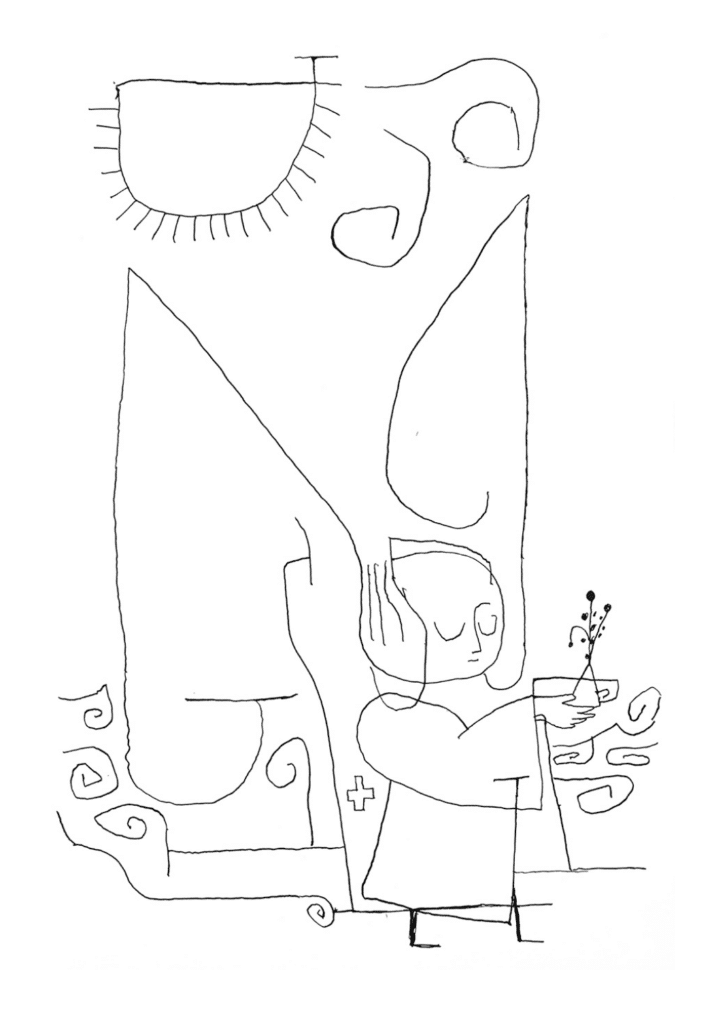

Angel Brings Needed Medicine

Sanda Iliescu

Watercolor on Paper, 2021

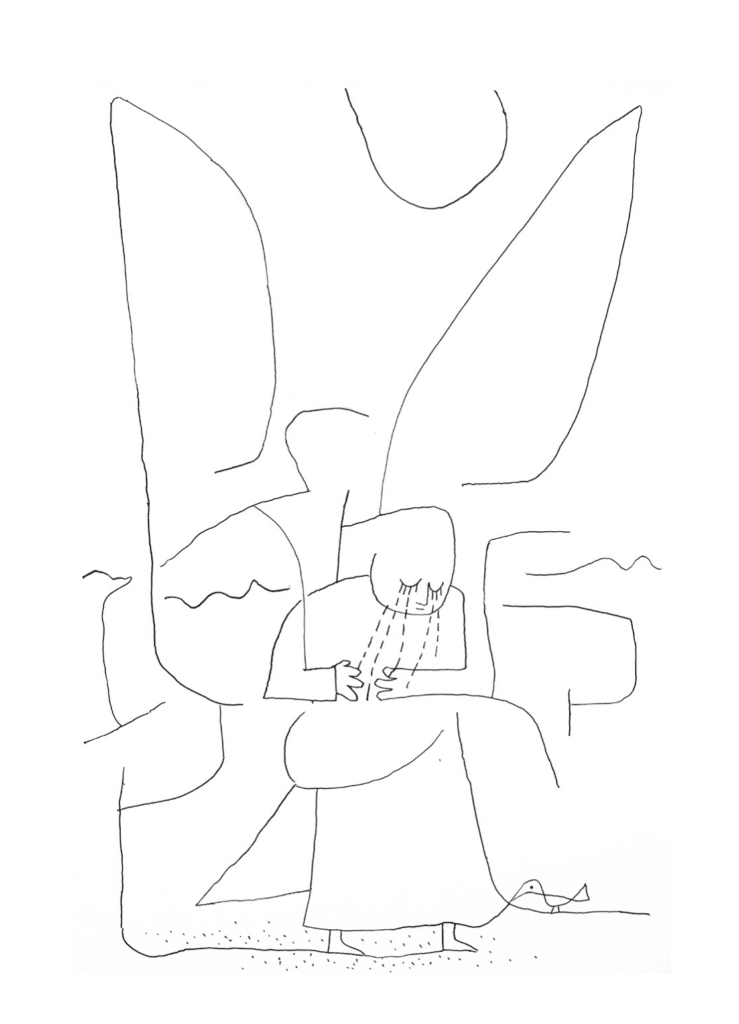

Angel Crying with Bird

Sanda Iliescu

Watercolor on Paper, 2021

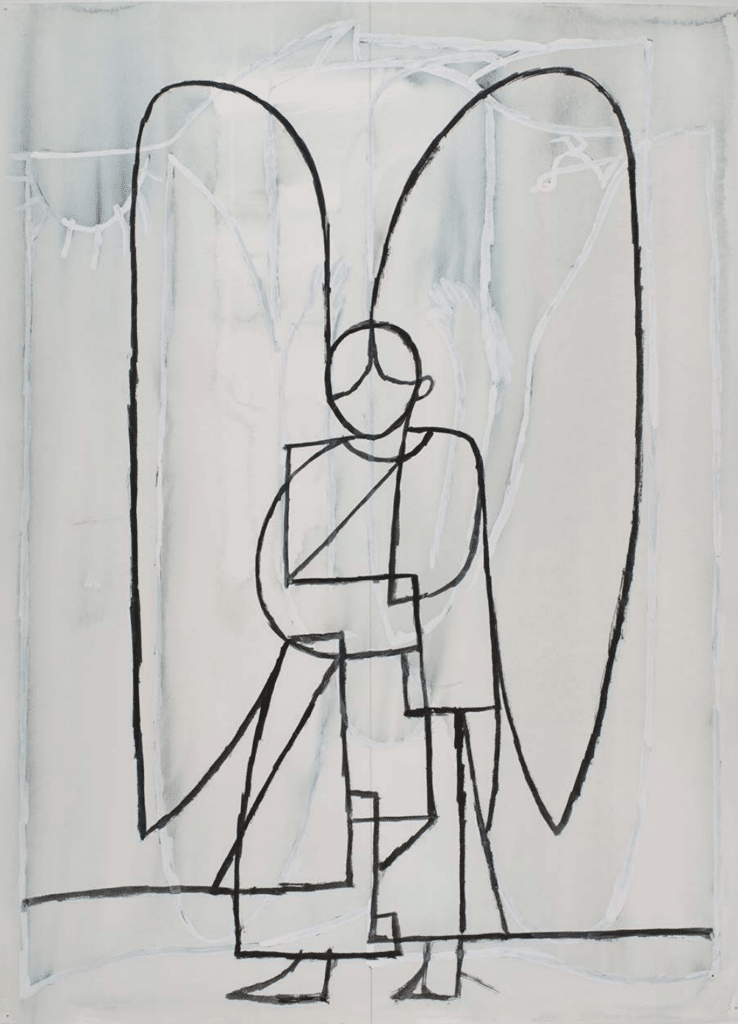

Poor Angel

Sanda Iliescu

Watercolor on Paper, 2022

References

i J. Heath Atchley, Encountering the Secular: Philosophical Endeavors in Religion and Culture (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2009)

ii Eckhart Tolle, The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment (Novato, CA: New World Library, 1999)

iii Donald Barthelme, Sixty Stories, (New York, NY: Penguin Group, 1993),135.