Mark Baechler and Tammy Gaber

Laurentian University School of Architecture, Sudbury, Ontario mwbaechler@laurentian.ca, tgaber@laurentian.ca

Introduction

And Lord said to Abram, “Go forth from your native land and from your father’s house to the land I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, And I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you shall be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and curse him that curses you; and all the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you.” – Genesis 12:1-3[1][2]

At that time Jesus came from Nazareth in Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan. As Jesus was coming up out of the water, he saw heaven being torn open and the Spirit descending on him like a dove. And a voice came from heaven: “You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.” – Mark 1:9-112

Recite in the Name of your Lord Who created. He created the human being from a clot.

Recite: Your Lord is the Most Generous, He Who taught by the pen.

He taught the human being what he knows not. – Qur’an, al-‘Alaq 96:1-53

The Abrahamic God—worshiped by Jews, Christians and Muslims—is often called the ‘invisible’ God. When compared to others worshiped during the inception of Judaic monotheism, the Abrahamic God is devoid of a visual presence or image. Abram is introduced to his God through sound, he is called, and then he responds. The importance of sound in the Abrahamic traditions worship of their God is paramount. Yet, in the study of Jewish, Christian and Islamic architecture sound is frequently overshadowed by vision. Scholars often discuss and document the presence of light and darkness; colourful icons and prayer carpets[3] offer an endless architectural hermeneutic. However, in addition to the visual interpretation of synagogues, churches and mosques there is much to be gained in the study of their sound.

Is architecture an instrument that facilitates a sacred dialogue between the Abrahamic God and his people? The following paper discusses an unfolding Abrahamic Soundscape project inspired by this question. The project seeks to record and re-present, through the compilation of soundscapes, the acoustical characteristics of Jewish, Christian and Islamic architecture. Composed of music, prayer, silence, etc., the soundscape intercepts moments of sacred dialogue and the auditory experience of architecture.

The purpose of the project is to draw attention to the importance of the auditory experience within the Abrahamic religions’ buildings. Our research attempts to describe their architecture using sound. We select a number of synagogues, churches and mosques located in cities housing Jews, Christians and Muslims and record the call to prayer, rituals, songs, prayer, and architecture that connect the Children of Abraham to their God.

The first iteration of this project focused on Abraham’s houses in Sudbury, Ontario. We recorded two worship services at the Shaar Hashomayim synagogue, Fielding Memorial Chapel of St.Mark, and the Islamic Association of Sudbury mosque between 2014 to 2015. The services were documented with a Roland SD-2u Recorder, this device has dual microphones that sensitively capture the atmospheric sound in a space. The recorder was located centrally within each of the worship spaces. The raw recordings were collected, structured and edited into a soundscape using Audacity software.

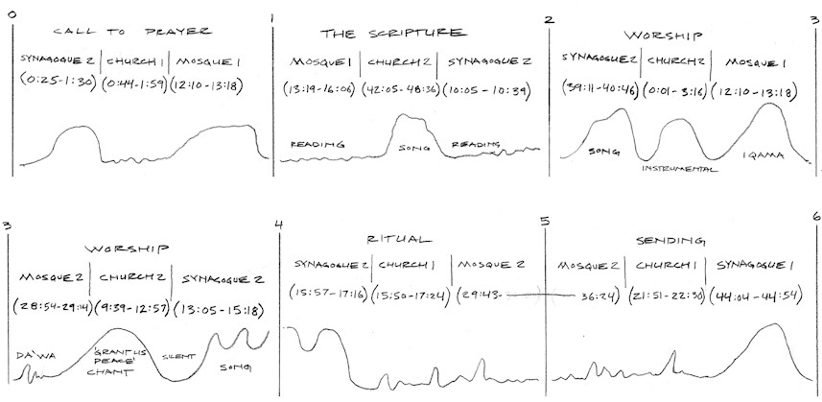

A study of the raw recordings revealed patterns and common rituals that informed the structure of the soundscape compilation. Our observations suggested that the soundscape open with a systematic layering of the call to prayer from each of the three spaces followed by scripture readings, melodic and musical worship, ritual worship and concluding with an invitation to speak God’s word in the world. Figure 1 illustrates the editing structure of the 35 minute soundscape.

Figure 1. Editing structure of Abrahamic Soundscape, Sudbury 2015.

Architecture as a Place of Sacred Dialogue

The Jewish, Christian and Islamic scriptures point to the importance of auditory dialogue in the revelation of the Abrahamic God, and form a foundation for the study of their ritual sound. In the Book of Genesis, God speaks to Abram and tells him that he will be the father of a ‘great nation.’ At this moment, Abram joins a select few[4] that have heard the voice of God. In time, Abram becomes Abraham and he begins a conversation with God that extends to his ‘great nation’ of Jews, Christians and Muslims. Abraham established a precedent for how believers are to communicate with the invisible God. And all those who followed Abraham from Moses, Jesus and Muhammad to the faithful among us, call to the Lord and listen for His response.

In the Book of Exodus, Moses is instructed to communicate with God by entering the Tent of Meeting—a structure designed for this specific use.[5] While secluded in contemplation, in a cave in Mount Hira near Mecca, the first word of the Islamic revelation heard by Mohammed[6] was ‘Recite,’ followed by the remaining verses of Surah 96 (al-‘Alaq). Mohammad is invited to ‘recite’ the revelation of God; he obeyed and later built a mosque in Medina.[7] In the Abrahamic scriptures, architecture is often described as an instrument to converse with God.

The tradition of architecture as a place of conversation between God and His people illustrated in the scriptures continues in contemporary Judaic, Christian and Islamic worship as revealed in the soundscape. We hear the invitation to worship at the beginning of the soundscape, Jews enter the synagogue reciting sabbath of peace, ‘Shabbat Shalom,’ similarly the threshold is traversed in a Christian prayer of call and response, and Muslims are called to submit to the greatness of God, ‘Allaho Akbar.’ The Children of Abraham are drawn into the architectural atmosphere of worship. The second part of the soundscape includes readings from the scriptures that articulate the tenants of individual Abrahamic faiths. Following the recitation of God’s word, worshippers voice their melodic offerings expressing exaltation. A single delicate voice calls out from the synagogue, a piano and cello rejoice in the Christian Messiah, the prolonged incantation of the name of God echoes in the mosque. In the fourth part of the soundscape requests to God are made, in the form of direct supplications Muslims ask for forgiveness and mercy and Christians chant ‘Dona nobis pacem’ (grant us peace) in the church, in the synagogue ritual prayer is recited in unison, followed by the Christian Eucharist and the formal prayer in the mosque. In the last part of the soundscape Jews, Christians and Muslims transition out of their conversation with God. ‘Assalamu ‘alikum wa Rahmatu Allah’ (peace be upon you and may God’s mercy be with you) is voiced by Muslims, the Reverend invites Christians to ‘go in peace to love and serve the Lord,’ the threshold of Jewish worship is crossed with ‘Shabbat Shalom.’ The cyclical nature of the services is reflected in the editing of the soundscape.

In the soundscape we hear the synagogue, church and mosque framing the sacred dialogue in the Abrahamic traditions. Several architectural scholars have written about the phenomena and clear relationship of sound and space including Juhani Pallasmaa,9 Steen Rasmussen,10 W.J. Ong[8] and others who describe architecture acting as an instrument as much as the source of sound. In their arguments, Christian churches are often cited as examples of buildings that offer an exceptional auditory experience.[9] According to religious scholar F.E. Peters, within the spaces of Abrahamic worship “…the Revelation comes full circle and is once again given voice by the very creatures to whom they were first addressed.”[10] Architecture is instrumental in shaping the sound of worship and is an active participant in offerings to God.

The Abrahamic Soundscape project extends from an argument that auditory dialogue in the Abrahamic religions is scriptural and of primary importance. Further, architecture is often a mediating instrument of sacred communication between the Abrahamic God and His worshipers. Our research suggests that an academic understanding of Jewish, Christian and Islamic architecture is incomplete without an interpretation of its unique ritual sound.

References

Nasr, S. H. Islamic Art and Spirituality. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987).

Ong. W.J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. (London: Routledge, 1982).

Pallasmaa, Juhani. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. (Cornwall: John Wiley & Sons, 2012).

Peters, F.E. The Voice, The Word, the Books. The Sacred Scripture of the Jews, Christians, and Muslims. (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2007).

Rasmussen, Steen Eiler. Experiencing Architecture. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1959).

Sahih Bukhari Arabic-English Translated. Mohamed Muhsin Khan, Trans. (Riyadh: Dar-us-Salam, 1996).

The Tanakh. (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1999).

The Holy Bible (NIV). (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Bible Publishers, 2002).

The Sublime Quran. English Translation. Laleh Bakhtiar, Trans. (Chicago: Library Islam, 2006).

Von Simson, Otto. The Gothic Cathedral. (New York: Bollingen Foundation, 1956).

[1] The Tanakh. p.21.

[2] The Sublime Quran.The Holy Bible (NIV). p.545-546. p.833.

[3] See discussion on light in Gothic Cathedrals in: Von Simson, The Gothic Cathedral, pp.3-20 and the discussion of the manifestation of divine cosmology in Islamic architecture in: Nasr, S. H. Islamic Art and Spirituality, pp.37-39.

[4] In the Book of Genesis, God also spoke to Adam, Eve, Cain and Noah.

[5] The Holy Bible (NIV), Exodus 33:7-11. p.75.

[6] The moment of revelation is described using Mohammed’s description in authentic ahadith documented in Sahih Bukhari, (Book of Revelations, 1:3). p.50.

[7] Al-Masjid al-Nabawī, commonly referred to as the Prophet’s Mosque in Madina. 9 Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. pp.53-56. 10 Rasmussen, S. E. Experiencing Architecture. pp. 224-237.

[8] Ong, W.J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. pp. 70-73.

[9] Rasmussen, S. E. Experiencing Architecture. p.231.

[10] Peters, F.E. The Voice, The Word, the Books. The Sacred Scripture of the Jews, Christians, and Muslims. p.247.