Alison B. Snyder

University of Oregon, Eugene (USA)

absny@uoregon.edu

an introduction

In this new project the author looks at social aspects and activities surrounding sacred buildings in urban settings. The main focus is on particular monuments in Istanbul, Turkey and other dense urban cities such as Rome, Italy where one may observe first-hand the open-ness and containment of similar and different sacred spatial, architectural and material characteristics. As a researcher who primarily does field work in Turkey, this project builds on previous work that was concerned with how the need for light and lighting influenced the design and on-going use of Ottoman mosques (Snyder: 2000). It also ties in with other current research based in Istanbul that considers secular street spaces and their relation to changing global and local conditions.

For this paper, it is the setting of a mosque that needs examining. A mosque structure can take on different shapes, forms and sizes, and may be constructed in a very open or more closed manner depending on the different country and climate in which it is set. The internal spaces of these sacred buildings provide places for communal and individual prayer and contemplation; yet the external surrounding spaces provide a series of often blurrier spaces and uses, containing and posing different possibilities for readying oneself for spiritual engagement and also providing spaces for seemingly less spiritual activities.

The Fatih Cami (Sultan Fatih Mehmet Mosque) and its külliye (complex of surrounding buildings) in Istanbul were selected because of its location, personal allure and long history. The setting of Fatih Cami is located in a dense neighborhood out of the main tourist path, yet when visiting the külliye plaza and other spaces surrounding the mosque, the “collecting” of people has an aura worthy of discovery. The sacred site is located on a hill in the center of what is considered the Old City. The mosque serves social functions such as: a place for daily worship (and a limited non-Moslem tourist destination), a pilgrimage for those who want to visit the türbe (tomb) of Sultan Mehmet II and his wife’s, and a common place for small gatherings, comings and goings within a small park-like atmosphere.

Specific work regarding Fatih Cami and the relationships between paths and passages taken between mosque complex entries and exits was only found in a paper by Ziad Aazam who uses spatial syntax theory developed by Bill Hillier to compare several monuments all over the Islamic world (2007). In a less scientific way, this research asks why people are drawn to these spaces? How might we interpret normal and daily activities co-existing within a sacred zone? Central to this study then, are three groups of questions relating to: the everyday spiritual and secular activities and why these persist; architectural design differentiation and what makes it conducive to linking and separating different kinds of activity; and whether there is cognizance of the daily integrated with the sacred or spiritual.

Historical and architectural background

Aga-Oglu writes, “Ten years after the conquest [1453] the conqueror, Sultan Mehmet the II, ordered a ‘worthy’ mosque to be erected in place of the famous but already ‘dilapidated’ Church of the [Holy] Apostles (1930:179).” Previous to this hill site being a Moslem one 547 years ago, the site was a Byzantine one. Emperor Constantine christened it in 330 AD and Emperor Justinian rebuilt the church and consecrated it in 550. It was said to be second in importance to the Haghia Sophia and held important relics and sarcophagi. The church was robbed during the Crusades and was badly damaged in an earthquake in 1328, thereafter remaining unused until Constantinople fell (2005-10: website).

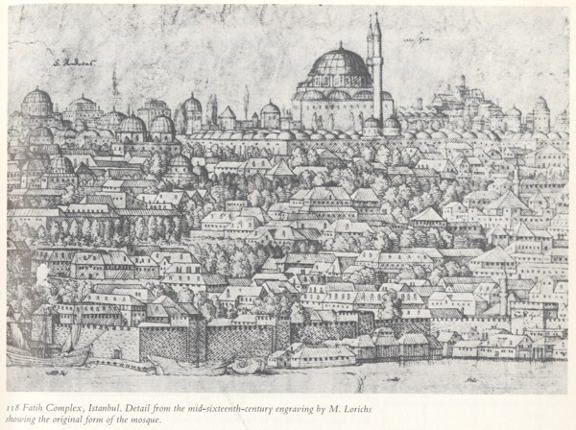

Fatih Cami has undergone a lot of architectural change but its site has remained similar to the original plan beginning in 1463 with several medrese (Koran school with libraries), imaret (soup kitchen), open spaces with planted gardens and a hard surface plaza, and other structures including the türbe (s) added later. Accounts of the frequent earthquakes during the mosque’s first 300 years cite 1768 as the most fatal one. The building standing now is from 1771 when the mosque plan originally based on multiples of twelve, said historian Godfrey Goodwin, was more regularized to form a square based on sixteen and looking much like other, mosques built in the 16th century, yet the overall size appears to be the same as the original, and still sits in the same place (1971). Pictured here is an historical illustration from the mid 1500’s showing the walled-in realm and the dense city (Goodwin’s book: 127).

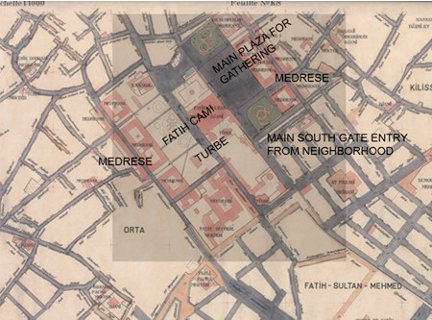

The siting of the mosque in the center of the large rectangular complex has its surrounding spaces laid out symmetrically in all directions (the full külliye measures 210 by 350 meters). Along the base of the mosque as well as in front of it are attached and freestanding fountains to perform ablutions before praying. These are perhaps the most sacred zones outside as they pertain to the ritual of cleansing and are directly associated with praying five times a day. Flanking these areas at street level are same-sized paved plaza zones with the largest areas to the NW and NE measuring 75 by 210 meters. To either side of them are grassy planted areas and then bands of medrese. The paved plazas, especially the NE side, are where most of the other “activity” takes place. The külliye is essentially walled in and is approached from a variety of gates that connect spaces. The internal sacred zones are separated from the secular zones of the neighborhood, yet there appear to be daily routines that take place within the walls. Some of the character of the place is accessible through maps pre-World War I on an Alman Mavileri Haritalari (German Blue Maps) detail pictured on the left. An earth.google.com satellite image on the right taken in 2010 shows how it is virtually unchanged in almost 100 years.

What make this place hold sacred zones?

The siting of Fatih Cami offers many layers of ongoing built history and symbolism over 1,680 years. Phenomenologically speaking, the concept of this palimpsest holds literal and spiritual memories that can be understood and felt individually and communally. The words of architect Juhani Pallasmaa in The Eyes of the Skin, begins to address how we might understand the draw to a structure in the city and the ground space surrounding it. He says architecture mediates meaning for people by addressing “all the senses simultaneously and fuse[s] our image of self with our experience of the world. The essential mental task of architecture is accommodation and integration. Architecture articulates the experiences of being-in-the-world….” Pallasmaa goes on to say, “Significant architecture makes us experience ourselves as completed embodied and spiritual beings (2005: 11).”

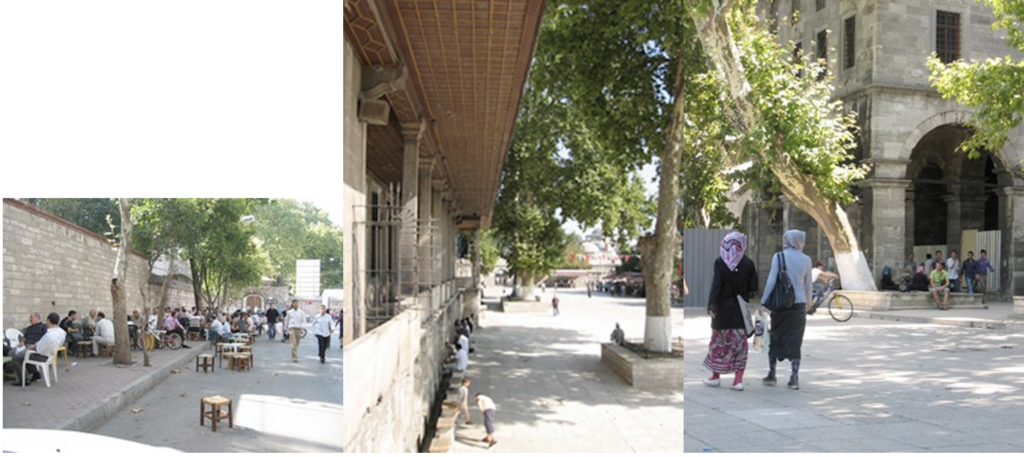

The relationship between the different day-to-day activities that people partake in outside of religious monuments is compared to the more ritualized activities that take place inside of them. The inside open spaces cater to many kinds of socializing including eating, resting, sewing, watching of children, small children bicycling and more. There is an easy mix of the genders, of the religious and less so, and there appears to also be a strong perception of protection and safety right alongside the open-ness and welcoming.

But why else do they come there? There must be an awareness of the phenomenological possibilities that points to people “needing or desiring” to be close to religious or built spiritual expressions, and thus, the reason for the kinds of basic daily activities and relationships exposed inside the walls of the külliye make space for different actions and emotions present outside. This may explain the inexplicable liminal experience of feeling comfort or calm when stepping from the outside through an arched gate to the realm of the side plaza (especially felt when nearer to the fountains) even if one has no intention of going inside the mosque to pray or visit the tombs. Once outside the gates, there is an almost immediate change of energy and experience. Photographs by the author exhibit the qualities seen in 2008 when there was also renovation work going on [outside the south gate, along the ablutions fountain and NW plaza, NE plaza scene].

Put another way, the “here/there” that Bachelard writes of in his chapter called “The Dialectics of the Outside and Inside” (1964: 211-231) allows us to recognize the simultaneity of the metaphysical and rational. Each inhabitant of the spaces surrounding the mosque participates at many levels. Others such as Eliade (1959), Norberg Schulz (1979), and Smith (1987), ask us to contemplate the sacred and profane, or secular, together. Patterns of social use in urban and religious contexts in eastern cities can begin to be understood through the writings of architectural historians such as Herdeg (1990), Kostof (1991), Kuran (1996), and Holod (1983, 1997) to name only a few.

Perhaps there is an awareness and knowledge that goes beyond the beauty of the building, the shape and scale of the ground space or the aesthetics of the surroundings when sitting and/or interacting in proximity of a sacred space. It cannot be overlooked that the religious temporal rhythm of the day for the Muslim, may translate into bringing people to the mosque zone throughout the day—everyone becomes a part of the temporal ensemble. The author proposes through her observation during visits over a few years, that the “outsider” tourist or visitor and the daily or weekly local “insiders” also share spiritual connections. The mosque and its surroundings offer an urban spiritual mediation zone set between the rest of the neighborhood and city.

Bibliography

Aazam, Ziad (2007)

“The Social Logic of the Mosque,” in the 6th International Space Syntax Symposium Proceedings, Istanbul

Aga-Oglu, Mehmet (1930)

The Fatih Mosque at Constantinople,” in Art Journal, College Art Association, New York, vol. 12, no. 2 June: 179-195

Bachelard, Gaston (1964)

The Poetics of Space, Beacon Press, Boston, MA

Eliade, Mircea (1959)

The Sacred and the Profane, Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich, NY

Goodwin, Godfrey (1971)

A History of Ottoman Architecture, Thames and Hudson, London

Herdeg, Klaus (1990)

Formal Structure in Islamic Architecture in Iran and Turkistan, Rizzoli, NY

Holod, Renata, Uddin-Khan, Hasan, Mims, Kimberly (1997)

The Mosque and the Modern World, Thames and Hudson, London

Kostof, Spiro (1991)

The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings Through History, Little Brown, NY

Kuran, Aptullah (1996)

“A Spatial Study of Three Ottoman Capitals: Bursa, Edirne,” and Istanbul in Muqarnas, E. J. Brill, Leiden, vol. 13: 114-131

Norburg Schulz, Christian (1979)

The Genius Loci: towards a phenomenology of architecture, Rizzoli, NY

Pallasmaa, Juhani (2005)

The Eyes of the Skin, John Wiley and Sons, NY

Smith, Jonathan Z. (1987)

To Take Place, University of Chicago Press, IL

Snyder, Alison B. (2000)

“Transformations, Readings and Visions of the Ottoman Mosque,” in A Historical Archaeology of the

Ottoman Empire, ed. by U. Baram, L. Carroll, Klewer Academic Press/Plenum Press, NY: 219-240

Alman Mavileri 1913-1914 Birinci Dunya Savasi Oncesi Istanbul Haritalari, (German Blues 19131914: Maps of Istanbul before World War I), Istanbul Buyuksehir Belediyesi Kutuphaneler ve Muzeler Mudurlugu, Istanbul (2006-2007) http://www.sacred-destinations.com/turkey/istanbul-church-of-holy-apostles.htm