Caitlin Turski Watson

Kliment Halsband Architects, New York, NY

watson@kliment-halsband.com

“I thought everyone knew that the purpose of art is to inspire the creation of a beautiful city.”[1]

Nevelson Chapel, photographs by the author

Louise Nevelson was one of the most significant American sculptors of the 20th Century. Her process was one of both careful selection and aggregation. Constantly collecting discarded fragments of wooden furniture, architectural ornament, and lumber from the gutters and alleys of New York, Nevelson reunified these pieces as large wall assemblages and free-standing sculptures painted in solid black, white, or gold and given new life through their participation in the world she created. She mused, “When I look at the city from my point of view, I see New York City as a great big sculpture.”[2] Her own works, which largely took the form of environmental installations, in turn operate not as representations of New York, but rather as reflections of a city of the mind crystallized into physical encounter—emotional impressions made spatial. Although her background was Jewish, Nevelson’s spirituality was expansive, and she was concerned with creating spaces that would foster a sense of experiential belonging. In 1974, this quality led St. Peter’s Church to commission her for the creation of a permanent public artwork in the form of the Erol Beker Chapel of the Good Shepherd, now known simply as the Nevelson Chapel, which would serve as a public space for quiet meditation within their new church at the foot of Citicorp Tower in Midtown Manhattan. Through an analysis of Nevelson’s use of light and movement in the chapel, this paper will examine both the continuity she establishes between the sensuous atmosphere of the work and the user’s mental space and the implications this has for the chapel as an alternative type of public space in Manhattan.

In 1980, Tom Armstrong, Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, wrote, “We are at a moment in history when many people who collect works of art are drifting away from any sense of responsibility to artists and public institutions. The work of art has too often become only a means for increasing private worth or self-aggrandizement.”[3] Cannot the same be said now, in this moment, of architecture? To an alarming extent, urban public spaces are no longer crafted with the well-being of their users in mind. Within current systems of privatized development, even purportedly public spaces double as branding strategies designed to attract capital—the Vessel at Hudson Yards, for example. It is a condition that befalls many of New York’s privately owned public spaces (POPS) and has contributed to a new aesthetic of openness seemingly developed with Instagram in mind, rife with indoor planting, glossy surfaces, and endless video walls, and generally anchored by some form of retail. As a counterpoint, the model presented by the Nevelson Chapel warrants thoughtful consideration.

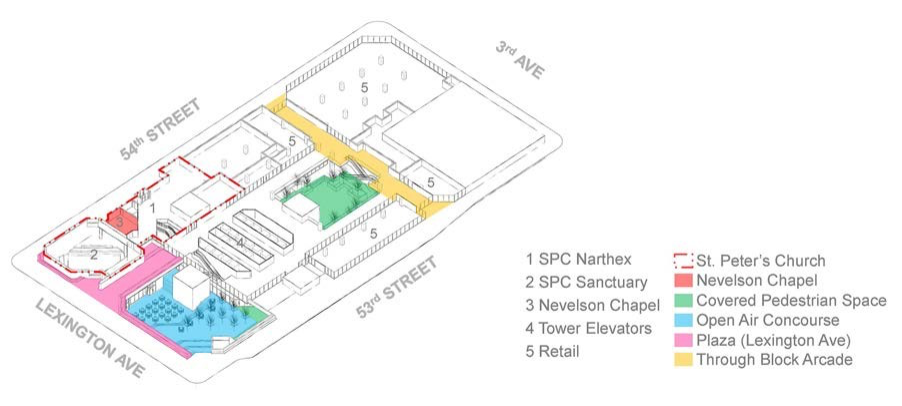

Following adoption of the 1961 Zoning Resolution, when Midtown Manhattan was targeted for commercial development, the congregation of St. Peter’s Lutheran Church determined that they would not only continue worshipping at their current location on the corner of 54th Street and Lexington Avenue, but that they would use this moment of neighborhood transition to “become a caring heart in the middle of Manhattan.”[4] Led by their ambitious young pastor, Rev. Ralph Peterson, the church forged an agreement with Citicorp to redevelop their entire block into a community hub and headquarters for the bank, with a new church building to be constructed on site. There is much to be said about St. Peter’s influence over other public spaces at Citicorp Center, but here we will focus specifically on the Nevelson Chapel, located at street level within the church’s narthex. Rev. Peterson was deeply committed to the relationship between religion and the arts, and he sought ways to leverage the physical space of the church to bring art into the public experience. Together with the congregation, he conceived the chapel as an ecumenical space for prayer and meditation—a place where “even the casual observer would be caused to contemplate that which no one can know.”[5] Easley Hamner of Hugh Stubbins Associates, the architect for the church and plaza, recommended Nevelson for the chapel commission, and Peterson, familiar with her recent exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, quickly agreed. He recalls, “I knew she could create an oasis in the middle of the city—mysticism in the midst of New York’s forest of skyscrapers.”[6] Nevelson was delighted by the opportunity. A close friend of Mark

Rothko, she had visited his studio while he was working on the murals for the Rothko Chapel in

Houston, an ecumenical enclave commissioned by John and Dominique De Menil in 1964. The De Menils were long-time friends of the Dominican priest Marie-Alain Couturier, who orchestrated the design of numerous sacred spaces in France by modern artists and architects. With the Rothko Chapel, the fusion of Couturier’s ideas and ecumenical institutions set the precedent for a new type of hybrid sacred-public space, intended to engage its users at both a physical and spiritual level. The Nevelson Chapel fits squarely into this lineage and demonstrates how such spaces might be imagined at the urban scale.

According to Nevelson, “New York is a city of collage. It has all kinds of people, all kinds of races, all kinds of religion in it.”[7] In her design for the chapel, she “wanted to break the boundaries of regimented religion to provide an environment that is evocative of another place. A place of the mind. A place of the senses” where people could “have harmony on their lunch hours.”8 In addition to a series of large wall assemblages, she designed the altar, sanctuary lamp, vestments, placement of pews, finishes, and lighting.

Aerial view of Citicorp Center, photograph by Norman McGrath, 1978, source: The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Axonometric View of Citicorp Center, Street Level, drawing by the author

This was consistent with her broader approach to sculpture. Beginning with her 1958 exhibition Moon Garden + One at Grand Central Moderns, Nevelson was primarily concerned with the creation of atmospheres. This insistence on the work of art as atmosphere was bound up in her understanding of metaphysics, particularly the fourth dimension—“the realm of spirit and imagination, of feeling and sensibility.”[8] Through art, Nevelson sought to pull the fourth dimension into perceptible experience in a drawing together of the body and the spirit. She wrote, “My total conscious search in life has been for a new seeing, a new image, a new insight. This search not only includes the object, but the in-between place; the dawns and the dusks, the objective world, the heavenly spheres, the places between land and sea.”10

Nevelson’s atmospheres function like the clearing of Being described by the philosopher Luce Irigaray in her work The Forgetting of Air. Critical of Heidegger’s definition of Being for presupposing a bodied physicality, Irigaray seeks to recover the lost union between the corporeal and the incorporeal, writing, “What consistency does the essence of Being have?… “Of what” [is] this is such that it remains invisible though it be the fundamental condition of the visible… unhindered in relating the whole to itself, and certain of its parts to each other… Of what [is] this is? Of air.”[9] She describes the clearing defined by air as “that perfect roundness where to be and to think are the same.”[10] In creating atmospheres, Nevelson celebrates this clearing, and she places the viewer at its center, inviting them to become an active participant in its unfolding. According to Rev. Peterson, “We are created to receive the Holy Spirit. We cannot be human unless we live ecstatically, participating in a larger reality,”[11] and it is this sort of ek-stasis that the chapel invites through a circular continuity between physical and spiritual experience.

Influenced by her study of cubism, Nevelson had a nuanced mastery of light and shadow.[12] Her early works were composed entirely in black, strategically illuminated with dim blue lighting to create an aura of mystery and enliven the shadowy interiors with sculptural depth. She prepared two maquettes for the chapel—one in white and the other in midnight blue and gold—and Rev. Peterson ultimately selected the white iteration, as he felt it was “a place in which New Yorkers will be able to pray and know that they are alive.”[13] Dawn’s Wedding Feast (1959) was her first atmosphere in white after five years of working exclusively in black. Nevelson associated white with the pale light of dawn, joy, and “marriage with the world.”[14] Her works overtake the walls of the chapel, becoming integral to the architecture. The space is evenly illuminated such that the sculptural walls capture shadows into themselves and reflect a diaphanous white light back into the room. While painted wood defines the edge of Nevelson’s environment, light and shadow provide the material-immaterial substance of a mood.

Nevelson originally titled the space Chapel of the Transfiguration. Rev. Peterson speaks of the inspiration she drew from the Tabor Light, the uncreated light revealed during the transfiguration of Jesus. While transformation is defined as a change in nature or appearance, transfiguration implies the revelation of a thing’s true nature. Transfiguration was central to Nevelson’s process, apparent in her attitude toward the discarded wooden fragments given new life through participation in her work. However, it also points to her intention for visitors to the chapel. She hoped it would be a space for people to come and “find [their] true being, [their] truer self.”[15] She spoke of New York as a city where people are always in a state of transformation, but the chapel provides a space where they can come to find themselves again. It pulls body and spirit back into unity within its pale light, pregnant with the hope and possibility of a new day. According to Irigaray, “It is not light that creates the clearing, but light comes about only in virtue of the transparent levity of air. Light presupposes air.”[16] Air functions as the mediator of the intangible, the bearer of light, while at the same time the appearance of light points toward the presence of the mediator—of something far more expansive and consequential than the light itself. Thus, the light has an outward orientation and points toward the bodied encounter of the spirit.

Nevelson Chapel, photograph by the author

Early in her career Nevelson studied dance and eurythmics, and it had a lasting impact on her work. She reflected, “Dance made me realize that air is a solid through which I pass, not a void in which I exist.”[17] As a result, experiences of her atmospheres take on the quality of a careful choreography. The chapel is not a space of stasis. A pair of plain wood doors provides passage into the chapel from St. Peter’s narthex. Upon entry through the doors, you are bathed in white light. Pews angled toward the center aisle draw your focus toward the altar opposite you. On sitting, the angle of the pews pulls your gaze to the perimeter, and the large wall sculptures slowly carry your eye around the room. You move within each piece and between pieces until finally, fittingly, the movement is halted by the introduction of gold at the crucifix, bathed in natural light and shimmering like the sun. You pause to dwell with it until a subtle shift in the air—caused, perhaps, by another visitor opening the door—sways the three hanging columns at the periphery of your vision, and suddenly you are moving again. “Movement = life.”[18]

Irigaray writes, “Granting privileged rank to vision, man has already accomplished an exit beyond the borders of his body. The subject is already ecstatic to the place that gives rise to him.”[19] At the chapel, this expansion of vision is the bodied reflection of a corresponding stretching of the spirit. Man and the world are reunited through the double operation of assimilation and participation,22 a communion made possible through sensuous engagement with Nevelson’s atmosphere.

Through the careful use of movement and light, Nevelson tunes visitors simultaneously to their own bodies and to the presence of others within the space. In this, the chapel operates as a communal vehicle for personal transformation. Perhaps the most incredible aspect of the Nevelson Chapel is its radical openness. It asks nothing of its visitors—no membership, fee, or ticket is required for entry. At any moment it may be occupied by a tourist experiencing the city for the first time, a worker in search of a quiet place to spend lunch, an artist seeking inspiration, or any weary New Yorker needing a moment of retreat from the city. Irigaray argues, “When the world becomes too built up and populated, the mind or the soul too preoccupied or burdened with knowledge… having recourse to spaces that are still empty… is essential. But an emptiness that is nonetheless encircled: the clearing of the opening.”[20] The chapel opens like a warm embrace in a city where entry is customarily transactional. Nevelson wanted the chapel to be “a place to go in despair—to find a quiet, warm, beautiful place… where people can solve what bothers them.”[21]

Currently, all of Citicorp Center, now rebranded as 601 Lexington, is being heavily renovated by Boston Properties, a commercial real estate investment trust. The changes will significantly alter the plaza outside St. Peter’s and the indoor public spaces at the base of the tower. This overt commercialization, a perfect example of the new aesthetic of openness, is intended according to the Department of City Planning “to produce more visible and vibrant public spaces with upgraded retail space.”[22] The design gives clear deference to marketability of the retail component and leverages any increased visibility or vibrance to this end, bringing to mind a question posed by Irigaray: “What if he who gives you air gives you air so rarefied, or compressed, or pure, or polluted, … that he, in effect, gives you death?”[23] Coincidentally, and completely at odds with this trend, the Nevelson Chapel is also undergoing a renovation, including conservation of Nevelson’s wall panels, to ensure that the chapel can remain open and accessible into the future. Once this physical renewal is complete, St. Peter’s intends to turn to the chapel’s programming to consider how the space can best serve the ever-changing city and how it can become a more active bridge between the faith and art communities.

In an increasingly divided world, we need public spaces that exist to reconnect us physically and spiritually with our selves and others. Nevelson lovingly described the chapel as “a place for all people”[24] and “a gift to the universe.”[25] When we consider it as an urban intervention, this is especially significant. Through the gift of common space, St. Peter’s sought to foster the overlap of disparate communities, dialogue rooted in mutual care, and the spirit of a life lived together. To this end, sacred-public spaces like the Nevelson and Rothko Chapels meet deep needs for continuity between physical and spiritual experience that are rarely acknowledged by conventional development, and they represent an important contribution to the fabric of urban life.

References

Hugh Stubbins Associates. Architectural drawings. St. Peter’s Church Archive, St. Peter’s Church, New York, NY.

Pastor Jared Stahler, interview with the author, October 10, 2018.

“Renewing a Masterwork: Nevelson at the Intersection.” Salon at St. Peter’s Church, New York, NY, October 2, 2018.

[1] Laurie Lisle, Louise Nevelson: A Passionate Life (New York: Summit Books, 1990) 174.

[2] Louise Nevelson, Dawns and Dusks: Taped Conversations with Diana Mackown (New York: Scribner, 1976) 96.

[3] Edward Albee, Louise Nevelson: Atmospheres and Environments (New York: C.N. Potter, 1980) 8.

[4] St. Peter’s Church, Life at the Intersection (New York: Development Task Force, 1971) 11

[5] From a letter written by Easley Hamner in Laurie Wilson, Louise Nevelson: Light and Shadow (New York:

Thames & Hudson, 2016) 367.

[6] Amy Levin Weiss and Ralph E. Peterson, “A Living Room Chat,” in Religion and Art in the Heart of Modern Manhattan, ed. Aaron Rosen (Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2016) 14.

[7] Wilson, Louise Nevelson: Light and Shadow (2016) 373. 8 Wilson, Louise Nevelson: Light and Shadow (2016) 366.

[8] Hans Hofmann in Laurie Lisle, Louise Nevelson: A Passionate Life (New York: Summit Books, 1990) 64. 10 Louise Nevelson papers, circa 1903-1982, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 5 Folder 30.

[9] Luce Irigaray, The Forgetting of Air in Martin Heidegger, trans. Mary Beth Mader (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999) 4-5.

[10] Irigaray, The Forgetting of Air (1999) 10.

[11] Weiss and Peterson, “A Living Room Chat,” in Rosen (2016) 12.

[12] She said, “Cubism gives you a block of light. A block of space for shadow. Light and shade are in the universe, but the cube transcends and translates nature into structure.” Lisle, Louise Nevelson: A Passionate Life (1990) 70.

[13] Wilson, Louise Nevelson: Light and Shadow (2016) 364. Peterson had seen Nevelson’s first environment in white, Dawn’s Wedding Feast (1959), at the MoMA.

[14] Lisle, Louise Nevelson: A Passionate Life (1990) 189.

[15] Louise Nevelson papers, circa 1903-1982, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 5 Folder 29.

[16] Irigaray, The Forgetting of Air (1999) 167.

[17] Lisle, Louise Nevelson: A Passionate Life (1990) 93.

[18] Louise Nevelson, “Merce the Magician” in Louise Nevelson papers, circa 1903-1982, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Box 5 Folder 31.

[19] Irigaray, The Forgetting of Air (1999) 99. 22 Irigaray, The Forgetting of Air (1999) 81.

[20] Irigaray, The Forgetting of Air (1999) 8.

[21] Wilson, Louise Nevelson: Light and Shadow (2016) 366.

[22] NYC Department of City Planning, “Interdivisional Meeting Record Re: 601 Lexington Avenue – POPS Redesign,” October 8, 2015.

[23] Irigaray, The Forgetting of Air (1999) 7.

[24] Wilson, Louise Nevelson: Light and Shadow (2016) 366.

[25] Grace Glueck, “White on White: Louise Nevelson’s ‘Gift to the Universe’,” New York Times, October 22, 1976.