Linda Reeder, FAIA, LEED AP

Central Connecticut State University, Department of Manufacturing & Construction Management reederlin@ccsu.edu

Summary

Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter was an architect and decorator for the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railway and their hospitality partner company Fred Harvey during the first half of the 20th century. Colter worked on numerous projects throughout the Southwest but is best known for the eight buildings she designed at the Grand Canyon. The Grand Canyon was (and is) sacred to many people, through both ancestral tradition and transcendent experience. In 1930, Colter was asked to design what became the Indian Watchtower—now called the Desert View Watchtower—at the east end of Grand Canyon National Park. Colter’s priorities for the project were to tie the building into its natural surroundings yet provide views in all directions. To achieve her goals, she borrowed and adapted regional Native American building types, construction techniques, and art. Through the Watchtower’s relationship with and connection to the Grand Canyon, Colter created a space for visitors to experience the Grand Canyon, and to be moved.

Sacred Experiences at the Grand Canyon

Indigenous people have lived in and near the Grand Canyon for millennia, and the canyon has spiritual significance for many. For example, the Hopi people are descendants of the ancestral Puebloans who once inhabited the Grand Canyon. The canyon is significant in traditional Hopi religion in many ways, including for containing the entrance to their underworld.[1]

Many later-arriving non-indigenous visitors have spiritual experiences at the Grand Canyon related to the landscape. Early geologists called many of the buttes and mesas inside the canyon “temples” and named them after Egyptian, Hindu, Greek, and Roman gods. Naturalist John Burroughs vividly described the sense of awe he experienced upon first laying eyes on the Grand Canyon in 1909:

Words do not come readily to one’s lips, or gestures to one’s body, in the presence of such a scene. One of my companions said that the first thing that came into her mind was the old text, “Be still, and know that I am God.” To be still on such an occasion is the easiest thing in the world, and to feel the surge of solemn and reverential emotions is equally easy; is, indeed, almost inevitable. The immensity of the scene, its tranquillity, its order, its strange, new beauty, and the monumental character of its many forms–all these tend to beget in the beholder an attitude of silent wonder and solemn admiration.[2]

Development without Desecration

In the same article that Burroughs referred to the Grand Canyon as the “Divine Abyss,” [3] he remarked that he wished “that we had hit upon an hour when the public had gone to dinner,” as he found some visitors distracting and insufficiently reverent.[4] As Burroughs’ comments illustrate, the tranquility and wonder that attracts visitors to the Grand Canyon is imperiled by those same visitors. This inherent tension began as early as 1901 when a rail link to the Grand Canyon made it broadly accessible. In its first ten years as a national park, annual visitation increased fourfold, from about 44,000 in 1919 to 188,000 in 1929.[5] More and more visitors arrived by automobile, with travelers arriving by car exceeding those arriving by train for the first time in 1926.[6]

Roads were built or improved to meet the growing needs of motorists. In 1927, the new Desert Rim Drive brought motorists twenty-five miles east of Grand Canyon Village to views of the canyon and the Painted Desert.[7] Park concessionaire Fred Harvey turned to in-house architect Mary Colter to design a rest station and gift shop to serve tourists at this end of the park.[8]

Colter explained her design goals in a manual she wrote for Fred Harvey tour guides after the project was completed in 1932: “First, and most important, was to design a building that would become a part of its surroundings—one that would create no discordant note against the time-eroded walls of this promontory,” Colter wrote. She rejected a modern design and modern materials as incompatible with the site. [9] While the building should be in harmony with its surroundings, it also had to tower above them. “[W]e wanted a VIEW that would include the entire circle of the distant horizon,” Colter wrote. “The problem, with its two horns to the dilemma, seemed unsolvable.”[10]

Colter’s life-long interest in Native American art and culture led to her solution, what she called a “re-creation” of an ancestral Puebloan watchtower.[11] “The Tower would give the height we needed for the view rooms and telescopes; the character of the prehistoric buildings would make

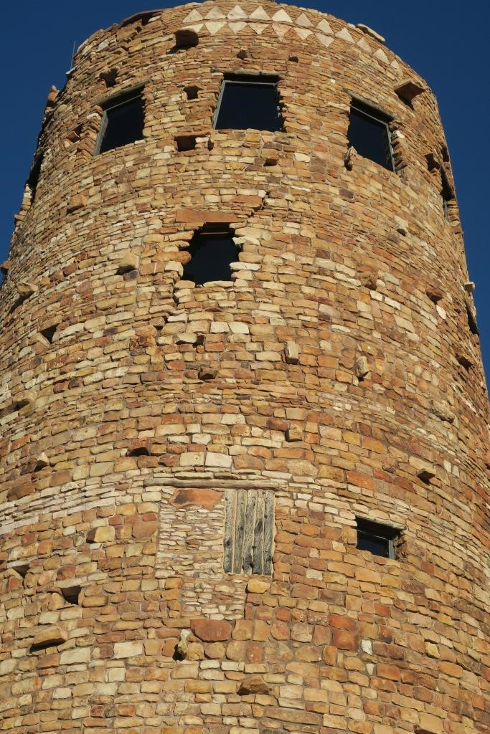

possible the harmonizing of its lines and color with the terrain; its time-worn masonry walls would blend with the eroded stone cliffs of the Canyon walls themselves”[12] (Figs. 1-1, 1-2).

Colter spent six months visiting and re-visiting prehistoric sites in the Southwest to study the remaining ruins of watchtowers and other structures. She observed, “The PRIMITIVE ARCHITECT never intentionally copied anything but made every building suit its own conditions and each one differed from every other according to the character of the site, the materials that could be procured and the purpose for which the building was intended.”[13] Colter adopted the same strategy, adamant that no one refer to the design of her Watchtower as a copy or a reproduction.[14]

Stone Craft

Colter was exacting in the construction of the Desert View Watchtower, particularly regarding the building’s stone exterior. She shared photographs from her research trips (Fig. 1-3) with the workers so they would understand the methods she was adapting.[15] Surface stones were collected from the surrounding canyon and used to build the walls.[16] Since cutting or tooling the stone would change its timeworn appearance, the stones were fitted uncut.[17] Colter designed masonry protrusions on the exterior face “to create shadows and give more vigor to the walls.”[18] She adapted other masonry features observed in prehistoric Puebloan buildings such as bands of different colored stones, wood lintels (which hid the structural steel lintels), and cracks (Fig. 1-4). A designed “ruin” adjacent to the tower adds to the sense of the structure’s long-term presence, as well as demonstrating the condition of many historic ruins.

Though similarly proportioned, at 70 feet high the Watchtower is much larger than its ancient predecessors. It required a concrete foundation and steel structure, both of which are hidden from view. Colter tied the building to the landscape and disguised the modern structure with large boulders at the base of the structure. These “simulate, as nearly as a man-made thing can do, the formation of the canyon wall itself. It is designed to look as though the whole foundation were another natural strata,” Colter wrote, “…and the boulders are so huge that they seem to preclude the possibility of being placed by man.”[19] Colter also mentioned the precedent for building atop boulders at the Wupatki prehistoric ruins just 30 miles from the Watchtower site.[20]

The View from Inside

The interior surfaces of the Watchtower are covered with Native American paintings, pictographs, and petroglyphs (Fig. 1-5). Colter hired Hopi artists Fred Kabotie to paint Hopi legends on the walls of the first floor gallery and Chester Dennis to inscribe petroglyphs. Additional pictographs throughout the building were made by Fred Harvey artist Fred Geary. Geary copied drawings and figures that had been found at ancestral Puebloan sites. In some cases, these decorations are the only record of the original drawings that remain today. Colter knew the symbols had great meaning to the Hopi people, writing that they considered art and religion to be synonymous.[21]

Windows are small and seemingly haphazardly located except at the two viewing areas. The top floor of the tower is ringed by large trapezoidal windows which afford views of the surrounding distant horizons. Telescopes both define and magnify the views. Colter outfitted the roof of the lower portion of the building with “reflectoscopes,” an adaptation of the technique used by Claude Lorraine and other landscape painters to flatten and frame the view. Colter said she provided these reflectoscopes to help people experience the landscape: “The general view of the Grand Canyon is so overpowering that separating a section of it for a moment and making it a ‘framed picture’—brings it better within ones comprehension.”[22]

Conclusion

By integrating Native American building types, techniques, materials, and paintings into the design of the Indian Watchtower and controlling views from it, Colter forged a connection with the Grand Canyon’s landscape and mystique. She borrowed and adapted ancient cultural traditions, giving the Watchtower a sense of the timeworn permanence consistent with its surroundings. Because of the Watchtower’s seamless connection with the canyon, visitors can behold the Grand Canyon’s beauty through the framed views and, as Burroughs described it, almost inevitably “feel the surge of solemn and reverential emotions.” [23]

Fig. 1-1. Desert View Watchtower. (Michael Quinn/National Park Service, 2010. https://www.flickr.com/photos/grand_canyon_nps/4690620989/in/photostream/)

Fig. 1-2. Desert View Watchtower. Colter called the one-story circular portion of the building the

“kiva,” another reference to ancient Puebloan architecture. (Linda Reeder, 2015)

Fig. 1-3. Mary Colter looking out through the door of an ancient Puebloan twin tower ruin in Hovenweep, Utah. (Unknown photographer/Fred Harvey, c. 1931.

Fig. 1-4. Desert View Watchtower (detail). Note the surface texture, the deliberate cracks at the corners of the window, and the T-shaped opening filled with different materials, as if at a later time. (Linda Reeder, 2016)

Fig. 1-5. Interior view of the Watchtower. The paintings on the lower level are by Fred Kabotie. Chester Dennis incised the petroglyphs. (Linda Reeder, 2016)

[1] Hughes, J. Donald. In the House of Stone and Light: Introduction to the Human History of Grand Canyon. (Grand Canyon, Arizona: Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1978) 11-12.

[2] John Burroughs, “The Grand Cañon of the Colorado,” The Century Magazine (January 1911: 425437, http://www.unz.org/Pub/Century-1911jan-00425?View=PDF) 426-427.

[3] Burroughs 428.

[4] Burroughs 428.

[5] Michael F. Anderson, Polishing the Jewel: An Administrative History of Grand Canyon National Park (Grand Canyon, Arizona: Grand Canyon Association, 2000) 90.

[6] Hughes 87.

[7] Hughes 87.

[8] Virginia L. Grattan, Mary Colter: Builder Upon the Red Earth (Grand Canyon, Arizona: Grand Canyon Natural History Association, 1992) 67.

[9] Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, Manual for Drivers and Guides: Descriptive of The Indian Watchtower at Desert View and its Relation, Architecturally, to the Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest (Grand Canyon National Park: Fred Harvey, 1933) 10.

[10] Colter 10-11.

[11] Colter 12. While Colter never used the term “Anasazi,” readers may be more familiar with it than

with “ancestral (or prehistoric) Puebloan.” The word “Anasazi” is believed to come from a mispronunciation of a Navaho word that can mean “ancient enemy.” Along with many (but not all) scholars, I have chosen to use more neutral terminology.

[12] Colter 11.

[13] Colter 12.

[14] Colter 11-12.

[15] Colter 11.

[16] Colter 13.

[17] Colter 12.

[18] Colter 17.

[19] Colter 14.

[20] Colter 14.

[21] Colter 22.

[22] Colter 44.

[23] Burroughs 426.