Dennis Alan Winters

Tales of the Earth : Landscape Architecture, Toronto, Ontario, Canada gardens@talesoftheearth.com

Although divinity might be in nature all around, not all landscape is created equally. Encounters with sexually charged landscapes provide potential for unencumbered highly charged transactions with spirituality. Ghost Ranch and Georgia O’Keeffe’s spirit provide the perfect opportunity to reveal layers beyond ‘mother earth’ imagery of the mantra: ‘Landscape is all about Sex’.

The sexually charged landscape is a multi-layered theme. Uniquely appearing as a distinct form in space, or distinct space surrounded by form, it invites attention to erotic shapes and spaces remarkably similar to human sexual organs. Caves like open vaginas, pairs of mountains spread to reveal shrub-like pubic hair or prominent breasts, and rock obelisks like enlarged penises. These landscapes charge spiritual practitioners and affect where peoples live. Primal cultures are drawn to these landscapes of raw sexual power, the play of male and female consorts of cosmic consciousness and the natural process. 1

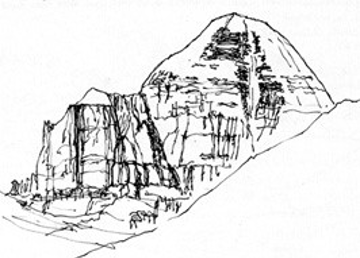

Fig. 1 Cerro Churequella Sucre

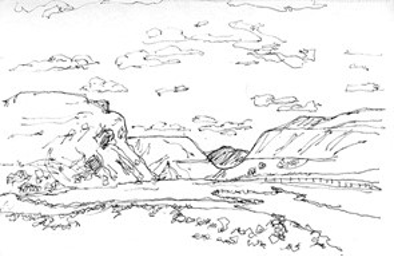

Fig. 2 Mt. Kailas

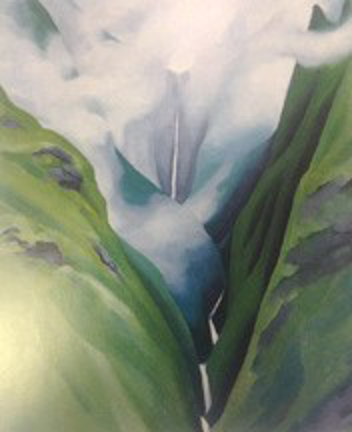

Georgia O’Keeffe’s landscape paintings provide a platform for aesthetic departure. Sculpted contours surrounding V-shaped compositions; the unrestrained metaphysical passion of nature: Ghost Ranch Cliff and Waterfalls of Iao Valley provoke penetrating questions: ‘Refined geological formations or “Outpouring of sexual juices, loamy hungers of the flesh;’ as Lewis Mumford wrote, “One long, loud blast of sex.”2

Almost anything seems layered with sex. Edmund Burke’s aesthetics portrayed male-driven lines of the sublime pirouetting with female-driven beautiful curves.3 Villa Gamberaia tied its classical renaissance garden to the cave of its erotic fruitful deity. ‘Cross Valley Syndrome’, a pedagogically priggish term linking geomorphology and psychology, likened the river breaching a mountain barrier to passage into soft and voluptuous enchantment. Why? Because people mentally transform Earth parts into human body parts.4 ‘Flirting with Boulders’ in Yosemite, engaging with landscape ‘pregnant with possibilities’ gave credence to the phrase, ‘getting your rocks off’.5

Is sexual imagery programmed? Buddhist sutra and tantra introduce the bardo, migrating through the intermediate state between lifetimes,compulsively focused on sex organs of a copulating couple with whom it has a karmic connection. The primal desire for one and equally strong aversion for the other determines its sex for the subsequent lifetime.6

Carl Jung wrote: How few things there are that can’t be reduced to the instinct of sex. Whether called libido or primordial psyche, that driving strength of our own soul is to make life proceed; it’s the love for life, for the beautiful, for the strength to fabricate good and avoid the not so good. This driving life force and instinct has a visual expression – the appearance of the phallus, while the expression of the natural order of things in which life, creativity and transformation is made possible is the vagina. They are found right here in the diversity of natural phenomena. Even the Rig Veda interpreted the world as an emanation of the libido.7

Wondering about the relationship between libido and landscape, I hear James Hillman and fellow eco-psychologists question the boundary between the psyche of people and psyche of the earth. I hear William Blake and Merleau-Ponty and Paul Brunton and Rene Magritte say: We see sex outside ourselves even though it’s only a mental fabrication of sex we experience inside. I hear Soto Zen master Dogen say: I came to realize clearly that the sexually charged mind is no other than mountains and rivers and the great earth.

Is all this a delusion? Here, the Buddhist Compendium of Ways of Knowingquestions the validity of objects that appear to consciousness.8 Hence, Georgia O’Keeffe responded to her critics’ fantasies, “My paintings erotic? No way! That’s something people themselves put into them. When people read erotic symbols into my paintings they’re really talking about their own affairs.”9 “Surely, you jest!” they snicker.

Fig. 3 Ghost Ranch Cliff Fig. 4 Waterfall 3, Iao Valley

Will landscape allow deeper access?

The correspondence between the Mahayana Buddhist views with which I’m familiar and other disciplines intrigue me. Plotinus said: All the Beauty and Good of this world comes by

Communion with Divinity. Dionysius Areopagite said: The whole of Nature moves together in rest and motion, brought into existence through the Beautiful and the Good; two names of God. Jung said: It seems to me that the high mountains, rivers, lakes, trees, flowers and animals far better exemplifies the essence of God than the clergy. Accordingly, I might well speak of ‘God’ as synonym for the unconscious.10

Here’s divinity, advancing a spiced-up contrarian interpretation of our relationship with landscape: That the sexual prowess of earth, waters and skies has had the upper hand in cultivating its relationship with our everyday perceptions. By way of the aesthetic languages that accord with our cultural familiarity with things, divine imagery has gloriously presented the evolution of landscape’s teachings on the sensuality of nature. Revealing her most private parts, nature’s intention all along has been to illuminate our providence as sensual and sexual beings as nature intended. Rather than appearing to succumb to our allegorical anthropomorphizing of hills and valleys as sexual body parts, perhaps it’s that the earth divine has geopomorphized human beings. Georgia O’Keeffe merely painted what landscape intended – displaying landscape in all its divine erotic fullness.

As landscape once again has its way with us, how deeply can this go? What would Georgia O’Keefe do with it? A Tibetan Buddhist text says:

For those not on spiritual paths, places provoke raw undisciplined passion.

To aberrant minds, landscape is just earth, stone, water, and trees.

To mistaken intellects, it appears as solid, inanimate objects.

To practitioners, it appears with no intrinsic nature.

To pure vision, it is a celestial palace full of deities.

To realization, the radiant luminosity of innate awareness.

And among the signs of confidence that a landscape is truly a sacred place are self-arisen landforms as penises and vaginas.11

I hear Tom Berry say, “Step carefully, for this is the kind of landscape where we are most aware of being present in the universe; where we are most ourselves in the context of our relationship with others.12

The Hindu tantric landscape,for example, would energize O’Keeffe with licentious imagery of cosmic divinity: male primordial consciousness purusha arising as erect lingam uniting with female cosmic and natural rhythm prakriti animating as yoni; their uniting producing life-force prana manifesting as form and space; the continuum of creation, maintenance and dissolution.

Spiritual geography painted as physical geography, fifty-one body parts of Sati’s cosmic and natural rhythm materialized through Shiva’s dance of dissolution as fifty-one sacred landscapes. Kamakhya in Assam State is her vagina, where a stone in a natural cave at the peak of the mountain of love is kept moist by a natural spring and turns red like menstrual blood when mineral deposits are flushed out by monsoon rains. As a Hindu tantrika, O’Keefe’s inner body would correspond with the cosmos through yogic sex harnessed in its most creative ways.13

The Vajrayana Buddhist landscape would energize O’Keeffe with profound practices harnessing subtle channels, chakras and vital essence energized by the deities Heruka and Vajravarahi in tantric embrace. Of twenty-four sacred landscapes, component parts of their body mandala, Pretapuri in Western Tibet corresponds to the tip of their sexual organs, provoking intense arousal and penetration. The power of this landscape is derived from Vajravarahi, her wisdom massaging this place.

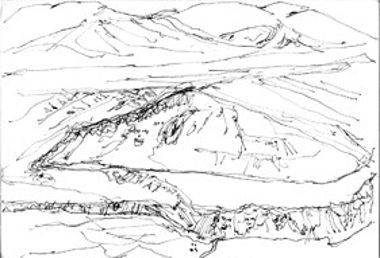

Fig. 5 Sutlej Valley, Pretapuri Fig. 6 Palace of 1,100,000 Dakinis, Pretapuri

Spiritual geography transformed into physical geography, O’Keefe would paint Vajravarahi’s sexual parts as geomorphology: braiding streambeds, valley, amphitheatre, rock escarpment and ‘self-appeared images of stone’, with vital essence orgasmically exploding into a broad majestic valley.

The Sutlej River, flowing through Pretapuri, is where the dakinis gather like a cloud. Erotic looking deities, dakinis make themselves available to tantric practitioners to help them cultivate the fully awakened mind. On the north side of the Sutlej River is the mountain called the Palace of the 1,100,000 Dakinis. A potent place; how would Georgia O’Keeffe use it?14

Tibetan Buddhism aims to cultivate full awakening, realizing the ultimate and relative truths taught by Buddhist philosophy. Full awakening requires advanced completion stage of Highest Yogatantra practices of meditation with an actual consort, because a Buddha’s omniscient mind is the indivisible union of a bliss consciousness cognizing emptiness appearing as Heruka; and wisdom appearing as Vajravarahi.

Meditating: ‘We are Heruka and Vajravarahi; our sex organ is Pretapuri’, O’Keefe and her embraced would generate inner abdominal heat, hold orgasm at their tips, focus on subtle drops flowing inside their central channels – the source of pleasure – untie channel knots at energy centres, and realize the awakened nature of the mind. Embodiment of the six perfections, landscape and the tantric couple merge as one. It’s not like ordinary sex.15

Now questioning if the role of sexually charged landscape serve merely as background to the provocative acts, or as the actual consort, itself. Because sacred landscape is blessed with the same essence as the awakened mind, the physical presence of that luminosity and knowing is revealed as earth, waters and skies, enabling O’Keeffe to paint her self portrait: Mind as Sex; Sex as Landscape; Landscape as Divinity; Divinity as Sex – highly charged transactions with spirituality.

Then re-questioning, freshly – Sexual juices or spirituality as landscape?

References

1 See Vincent Scully. The Earth, the Temple and the Gods (New York: Frederick Praeger, 1969):11, 14, 22;

E. C. Krupp. Skywatchers, Shamans & Kings (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997): 99-102; Catherine Tuck. Landscape and Desire (Gloustershire: Sutton Publishing, 2003); Gary Varner. “Folklore, History and the Study of Myth” http://garyrvarner.webs.com/cavesportals.htm referring to places like Mt. Kailas, Spider Rock, Cerro Churequella Sucre, Paps of Jura, Kawaiisu Cave, Carrizo Rock, Machrie Moor, Tent Rocks.

2 See Barbara Lynes. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Collections (NY: Harry N. Abrams, 2007); Randall Griffin. Georgia O’Keefe (London: Phaidon Press, 2014): 48; The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Fall 1984; Jerry Saltz. “Out of the Erotic Ghetto,” New York Magazine Art Review, 20 Sept 2009. 3 See Edmund Burke. A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful

(Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame, 1968); Mark Roskill. The Language of Landscape (The

Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park 1977); Peg Rawes. Space, Geometry and Aesthetics (Hampshire: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008).

4

See Paul Shepard. “The Cross Valley Syndrome”, Landscape, Vol. 10, No 3 Spring, 1961: 4-8.

5 See Sally Ann Ness. “Flirting With Boulders”. Journal of the Association of Cultural Anthropologists, No. 01/6 Sept 2011. 6 See Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey. Kalachakra Tantra (Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1985): 103; Lati Rinbochay and Jeffrey Hopkins. Death, Intermediate State and Rebirth in Tibetan Buddhism (Valois, NY: Gabriel/Snow Lion, 1979): 60.7 See Carl Jung. Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Vintage Books, 1989): 177,392; Carl Jung.

Psychology of the Unconscious (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1947): 128-137, 144-50, 368, 416.

- See A-kya Yong-dzin Yang-chän Ga-wäi Lo-dro. Trans. Sherpa Tulku and Alexander Berzin. A Compendium of Ways of Knowing (Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 1976).

- See Dorothy Seiberling, “The Female View of Erotica,” New York Magazine 7, no. 6 [11 Feb 1974]: 54. 10 See Plotinus. Stephen MacKenna, trans. The Enneads (London: Penguin, 1991): 47; Dionysius the

Areopagite, trans. C.E. Rolt. The Divine Names: The Mystical Theology (London: SPCK, 1920): 31; Carl Jung. Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Vintage Books, 1989): 45; Carl Jung. Psychology of the Unconscious (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1947): 336.

11

See Ngawang Zangpo. Sacred Ground (Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 2001): 158,179,181.

12 See Thomas Berry. Evening Thoughts (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 2006): 39, 115, 123. 13 See Rana Singh and Ravi Singh. “Sacred Places of Goddesses in India: Spatiality and Symbolism”; Amita Sinha. “Cultural Landscape of the Mother Goddess at Pavagadh”; Claudia Ramasso. “Some Notes on the

Kamakhya Pitha” in Rana P.B. Singh. Sacred Geography of Goddesses in South Asia (Newcastle upon

Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2010): 3-4, 53, 127, 163. Alsosee Ajit Mookerjee. Yoga Art (Boston: New York

Graphic Society, 1975): 24-34,41-44,85; Kapila Vatsyaya, ed. Kalatattvakosa (Delhi: Motilalal Banarsidass, 1988); Pranab Bandyopadhyay. The Goddess of Tantra (Kolkata: Punthi Pustak, 2002): 149; David Gordon White. Kiss of the Yogini (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003). 14 See Dennis Alan Winters. Searching for the Heart of Sacred Space (Toronto: The Sumeru Press, 2014): 88-89, 221, 245, 263; Dorje, Choying. “Story to the History of Pretapuri” in Bod I Jongs Nang bsTan (Tibetan Buddhism Magazine). Vol. I, 1990. 15 See D.L. Snellgrove. The Hevajra Tantra (London: Oxford University Press, 1959); Geshe Kelsang Gyatso. Essence of Vajrayana (London: Tharpa Publications, 1997): 98, 202, 210; Geshe Kelsang Gyatso. Clear Light of Bliss (London: Wisdom Publications, 1982): 23-24; Daniel Cozort. Highest Yoga Tantra (Ithaca: Snow Lion, 1986): 71, 88.

Figures

Fig. 1 Cerro Churequella Sucre by Dennis A. Winters

Fig. 2 Mt. Kailas by Dennis A. Winters

Fig. 3 Ghost Ranch Cliff by Georgia O’Keeffe, www.book530.com

Fig. 4 Waterfall 3, Iao Valley by Georgia O’Keeffe 1939, Honolulu Academy of Arts, CR 981

Fig. 5 Sutlej Valley, Pretapuri by Dennis A. Winters

Fig. 6 Palace of 1,100,000 Dakinis, Pretapuri by Dennis A. Winters