Rumiko Handa

University of Nebraska-Lincoln (USA)

rhanda1@unl.edu (email)

Architectural ruins are exemplary cases of architecture that entices the observers’ engagement. Each year all over the world tourists flock around ruins, invited by their physical state to contemplate on the lives of the people who are long gone, displaced for political, cultural, or unknown reasons. Ruins ultimately draw the observers’ attention to their own world and the self, to their infinitesimal occupation within the time’s continuum. The pedigree of such nature of architectural ruins may be identified in nineteenth-century Romanticism, expressed in the works of William Wordsworth and Sir Walter Scott. To study the interpretations of architectural ruins is to introduce a theoretical stance rarely taken in architectural history and criticism, which always have dealt with synchronic interpretations or the object’s meaning at the time of fabrication. Even without a reminder from a Poststructuralist we know an architectural piece often outlives its designer and supporting zeitgeist. This postulates a way of thinking about architecture on the basis of diachronic interpretation.1

Discussing “The Hermeneutical Function of Distanciation,” the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur

(1913-2005) rejected what had motivated Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900-2002) to write Truth and

Method, that is, the opposition between “alienating” distanciation and participatory belonging.2 For Ricoeur, distanciation is “positive and productive,” and an essential condition, not an obstacle, of interpretation. When a discourse turns from an event to a written text, it gains autonomy, away from reference or context that may otherwise give primacy to the meaning either by the author or the society. What must be interpreted then is not the original meaning hidden behind it but is “the world of the text” in front. To Ricoeur the world of the text is what “I [the interpreter] could inhabit and wherein I could project one of my ownmost possibilities.” As such, the text is self-reflective of the interpreter. A third kind of distanciation, while the first being Gadamer’s distanciation to be overcome between the interpreter and the author, and the second being Ricoeur’s notion of productive distanciation between the author and the text, then is that between the text and the reality, in the sense that through the interpretation, the everyday reality is “metamorphized by what could be called the imaginative variations which literature carries out on the real.”

Architectural ruins promote “positive and productive” distanciation in at least three ways. Firstly, architectural ruins like any other built objects have autonomy from the original meaning. Secondly, architectural ruins carry what Austrian art historian Alois Riegl (1858-1905) called “the age value,” based first and foremost on the signs of age by way of natural, or intrinsic, representation. It does not rely on the original for its significance, on which the “historical value” is based, nor does it depend on the viewer’s education or taste. Missing parts of the buildings, decayed stones, and growing vegetations are physical features of architectural ruins, although non-ruinous building could have a similar value by way of patina or weathering. Thirdly, the obvious lack of use or purpose further emphasizes the distance.

In William Wordsworth (1770-1850)’s works, the architectural ruin is a recurring theme that relates to the loss of life. “The Ruined Cottage” (1797) is a story of a cottager and his wife. Misfortune befalls, and the husband leaves home to join a troop of soldiers. The wife waits for his return till she dies in increasingly wretched situation, and the cottage falls into ruin. In “Michael” (1800), a story is told at the site of a ruined cottage. Faced with family misfortune and to evade the loss of the land, Michael decides to send his son Luke to the city. There, Luke disgraces himself and disappears abroad. Michael dies in grief. “Elegiac Stanzas Suggested by a Picture of Peele Castle, in a Storm, Painted by Sir George Beaumont” was written in 1806, a year after the loss at the sea of Wordsworth’s youngest brother John, captain of East India Company. It refers to the ruinous Piel Castle on a small island off the shore of Furness Peninsula of Cambria.

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) exercised Ricoeur’s third kind of distanciation by incorporating the actual historical events with those imagined, exuding the essence of a historical epoch and bringing the past closer to the reader.3 He made explicit references to ruinous buildings, from the observations at the site and reference to antiquarian and historical document.4 In Kenilworth: A Romance (1821) as in other historical novels Scott used two modes of writing: one, of the storyteller, who narrated the sixteenth-century events as if they had been taking place presently, and the other, of the antiquarian, who historicized the past from the nineteenth-century point of view.5 As Scott oscillated between these two modes, architectural ruins supplied a long passage of time, sometimes restored to the time of the events and other times in the state of ruin.

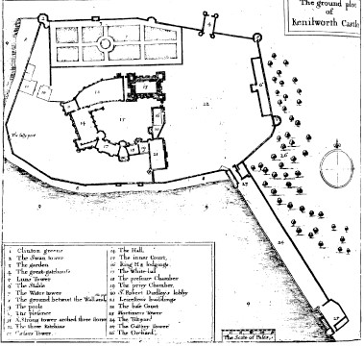

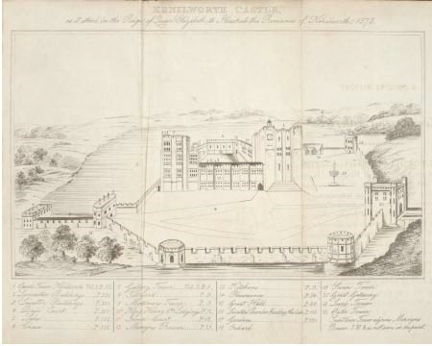

Firstly, just as protagonists were historical figures including Queen Elizabeth and Earl of Leicester, Scott set the story in actual buildings and the spatial relationships (figure 1). Secondly, just as he included the genealogy of the monarch and the nation, Scott used the names of the buildings that referred to history. Some were actual names from William Dugdale (1656) – Mortimer’s, Caesar’s, and Saint Lowe Towers, but one — Mervyn’s Tower (figure 2) – was created, whose murder in the Castle foreshadowed Amy’s. Scott also described the ornaments, whether actual or imagined, which referred to the building’s past. Thirdly, together with the manners and costumes, Scott described the architectural styles, for example of the Great Hall (figure 3), giving specificity of the time.

Fig. 1. William Dugdale, “The Groundplot of Kenilworth Castle,” The antiquities of Warwickshire illustrated (1656).

Fig. 2. “Kenilworth Castle as it stood in the reign of Queen Elizabeth to illustrate the romance of Kenilworth, 1575,” after the publication of Scott’s Kenilworth,“ 182?. A Strong Tower” of Dugdale is now called “Mervyn’s Tower” after Scott.

Fig. 3. John Britton, “Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire, View of Part of Hall,” The Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain (1835).

The discussion on architectural ruins has a wider application to that on architectural design that promotes participatory interpretation. Here “participatory” is used to specify the type of interpretation in which observers and inhabitants engage themselves in understanding the piece of architecture. Other architectural designs that encourage participatory interpretation may include those by Tadao Ando and Peter Zumthor, in which the observer’s attention is drawn to the few carefully selected and superbly constructed forms and materials. Either through distanciation or minimalism, architecture’s physical properties engage the observers and inhabitants in the participatory interpretation. Thus architecture has a way of contributing to the contemplation on the meaning of life.

Endnotes

1

While the 1970s’ application of semiotics discussed the architectural multivalence, this paper is not concerned with the change of meaning through time. Nor does it build a Deconstructionist argument for deferral. Instead it will focus on a specific nature of architecture, that which assists in associating the present to the past and then to the future.

2 Paul Ricoeur, “The Hermeneutical Function of Distanciation,” Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences:

Essays on Language, Action and Interpretation, ed. trans. and intro. By John B. Thompson (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press), 131-144. Originally published in French “La Fonction Herméneutique de la

Distanciation,” Exegesis: Problèmes de Méthode et Exercices de Lecture, ed. by François Bovon and Grégoire Rouiller (Neuchâtel: Delachaux et Niestlé, 1975), 201-14, which is a modified version of an earlier essay that had appeared in English in Philosophy Today, 17 (1973), 129-143.

3 Frederic Jameson, “Introduction,” Georg Lukács, The Historical Novel, trans. from the German by Hannah and Stanley Mitchell (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1983): 1. The English translation originally published: Boston: Beacon Press, 1963.

4 Scott invented the literary genre of historical novel, riding on the great wave of the nineteenth-century historical consciousness and demonstrating the understanding of one’s nation through its genealogy. Scott’s novels – Old Mortality (1816), Rob Roy (1817), The Heart of Midlothian (1818), Ivanhoe (1819), Kenilworth (1821), and Woodstock (1826) – are different from the earlier, “so-called historical novels of the seventeenth century” including Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otlanto, for which the past was an unfamiliar setting to entice the reader’s curiosities. See Georg Lucaks, The Historical Novel (London and Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983; reprint of the original, Boston: Beacon Press, 1963).

5 The story evolves around three historical individuals: Queen Elizabeth, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and Queen’s favorite, and Amy Robsart, Dudley’s wife. The first half tells about Amy Robsart staying at Cumnor Place. As Amy decides to visit Dudley at Kenilworth Castle, the story also shifts its place in the second half. Shortly after Amy’s arrival, Queen Elizabeth makes her royal visit to the Castle. Amy encounters the Queen but cannot tell her what she really is because the marriage between her and Dudley is kept secret from Elizabeth in order to advance Dudley’s position in the court. Amy eventually is taken back to Cumnor Place, and there she is murdered by the order of Dudley, who suspects her disloyalty to him. Contemporary reviews, both Scottish and English, praised the work for the “brilliant and seducing”

(Edinburgh Review) or “vivid and magnificent” (Quarterly Review, London) characterization of Elizabeth. The book had a great appeal among general readers, popularized the Elizabethan age, and ushered in nationalism.