Christopher Domin

University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona cdomin@u.arizona.edu

Introduction

Art and daily life conjoined is an aspiration that is often discussed, but rarely achieved. Discipline, thoughtful presence and time are necessary factors that allow for the translation of factual knowledge into reflexive action. Applied knowledge takes on many forms, but in the case of Judith Chafee (1932-1998), a careful balance was achieved between the prosaic, poetic and spiritual dimensions of human existence that extend from the domestic sphere into public life. This journey begins in a two-story adobe and along the arroyos of the Catalina Foothills where Judith Chafee spent her childhood under the close direction of her mother Christina Affeld— anthropologist, actress and designer. The making of adobe blocks and harsh lessons of the Sonoran Desert were formative experiences that helped Chafee negotiate the complex vicissitudes of her life. A move to the Francis W. Parker School in Chicago during high school brought her in contact with a pedagogy that was directed by the writings and counsel of John Dewey. An education based on the relevance of empiricism and primary source material. In fact, a life of action and learning though empirical engagement was reinforced by the politically engaged community in Tucson, Arizona in the 1930s and 1940s which took young Judith Chafee from meetings with Frank Lloyd Wright to public activism with family friend Margaret Sanger.

Chafee later was educated at Bennington College and Yale University along with a ten-year internship in the offices of Paul Rudolph, The Architects Collaborative (Walter Gropius, Ben Thompson), Eero Saarinen and Edward Larrabee Barnes, which placed her at the center of the architectural profession in the 1960s, but she became increasingly estranged from the selfreferential tendencies of the new generation. Judith Chafee came home to Tucson, Arizona in 1970 to begin her Arizona private practice based on values and priorities that she cherished. Her concern for essential conditions of site, culture, landscape and endemic materials were often in opposition to the dominant architecture culture that was taking shape in the Northeastern United States. Chafee was interested in an architecture where the making of a good room connected to the landscape could be an end in itself and the quality of light signaled the time of day or season of year. In this context, seemingly ordinary moments and objects were imbued with ineffable and, quite often, sacred qualities. This line of research will focus on Judith Chafee’s strategies of reengagement with Sonora on both sides of the border, through the formative years of architectural practice, with the goal of creating a meaningfully situated life of action.

East Coast

The May 1966 edition of Mademoiselle magazine included an article on the pros and cons of young women entering the architecture profession. Edward Larrabee Barnes’ office was singled out for its “integrated” male-female setting and Judith Chafee is prominently depicted with a model of the Yale University Campus and the Sterling Memorial Library. This publication offers one of the few instances of Chafee discussing the role of women in relationship to architecture.

“From childhood women are concerned with maintenance of the family; we are trained to provide comfort for those around us. When we cook, knit or arrange a room, we are — as in architecture — involved in a selection of tools and textures. A natural extension of traditional female concern for individuals is an interest in the city. As architects, our chief concern must not just be the relationship between buildings, but also the relationship between buildings and people.” Mademoiselle

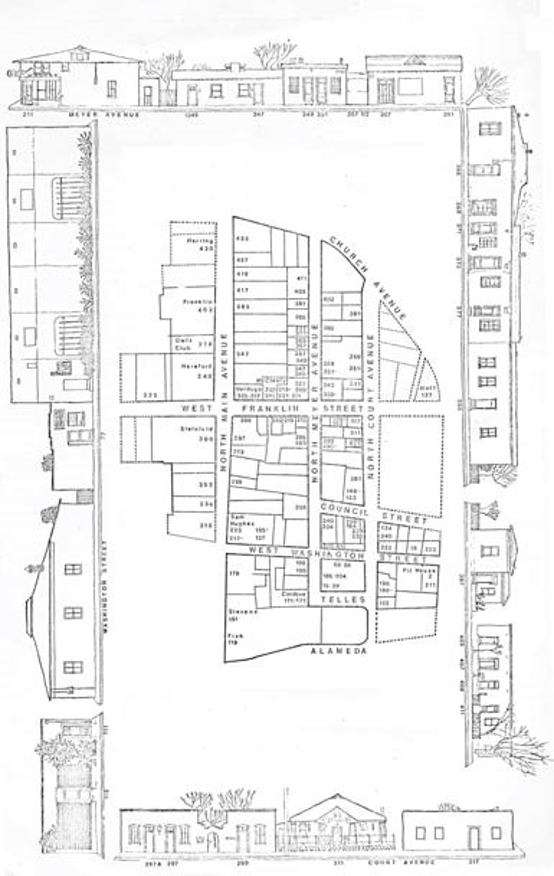

During this period, Chafee also ran a small private practice and was concurrently working on the Ruth Merrill Residence in Guilford, Connecticut that would place her on the cover of Architectural Record Magazine in the highly coveted Record Houses edition of 1970. This was also the year that Chafee purchased several connected buildings in the fabric of historic Downtown Tucson, Arizona, now know as the El Presidio Neighborhood. This complex would house Chafee’s practice for the reminder of her life and anchor the second phase of life in the American Southwest.

Judith Chafee, El Presidio Neighborhood Drawing, Chafee Studio located at 317 N. Court Avenue Image courtesy of Arizona Architectural Archives.

Southwest

After living for over fifteen years in Vermont, New York and Connecticut, Chafee returned to the city of her childhood, but one that no longer contained a family home or her biological parents. She entered a reordered city in which kinship and professional life needed to be rebuilt. In fact, the city was being reorganized in front of her eyes. The Pueblo Redevelopment Project of 1965 was well into a multi-year plan to clear a portion of Barrio Viejo and replace it with a Convention Center, City Government Buildings and Performing Arts Venues directly south of her El Presidio neighborhood. During this period, Chafee reconnected with her cousin Susan Bloom Lobo, a student of Anthropology at the University of Arizona, and they embarked on a series of trips that would help the architect frame the direction of her expanding practice. They headed south into Sonora along the Father Kino Mission Trail and spent time at Old Pasqua with family friend and eminent anthropologist Edward H. Spicer. The Pasqua Yaqui Easter Ceremony made a strong impression on Chafee as a young woman while visiting with her mother Christina Affeld, and later after returning full-time to Tucson, as an architect, the ritual continued to inspire both reflection and realization in building projects.

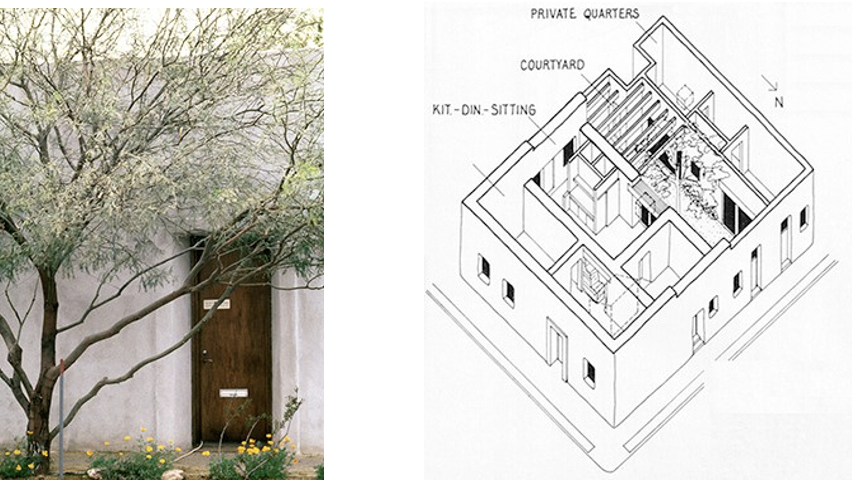

Judith Chafee Home + Studio Exterior and Illustration, Tucson, Arizona Glen Allison Photography, circa 1970. Drawing by J. Chafee.

Image courtesy of Arizona Architectural Archives

In the opinion of people who were close to her at this time— Chafee was not retreating to Tucson, she was directed toward something essential.

“I flee along the suburban Connecticut road with the Volkswagen on a high wine. I the woods are perfect glass houses, in the villages priggishly perfect white churches. The sides of the road are perfect. Placed stones, considered fences, ground covers and orange day lilies. The trees are beautiful, they crowd over the road and touch above. I think that I will drown in the green muck. I think that I will loose myself, my purpose, if I can’t see something beautifully naked and clear, if I do not see the edge of space—the horizon. I go to the seashore and find the space of the desert.” Artspace

The purchase of four two-room residences at the intersection of Court Avenue and Franklin Street was the first concrete act that allowed Chafee to reengage with Tucson. The two houses to the east were unstabilized adobes from the 1870’s and the western property was constructed of brick and dated from the 1930’s.

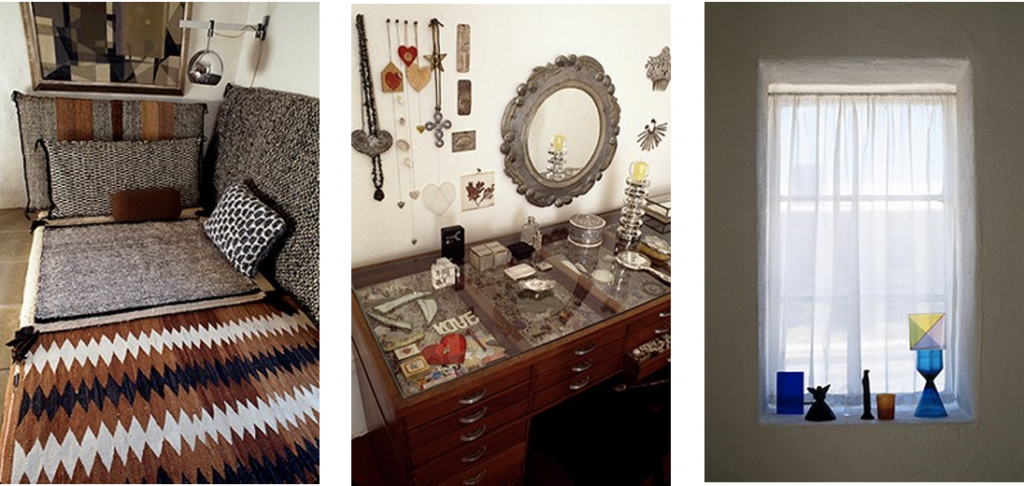

Judith Chafee Home + Studio Interior, Tucson, Arizona Glen Allison Photography, circa 1970.

Judith Chafee placed her architecture office in the adobe facing North Court Avenue and her private residence in the far western wing. Client meetings and office lunches were held in the dining area adjacent to the courtyard, which was created by removing the roof over one of the former residences. The public / private intersection takes place in the liminal space of the conference / dining area. An asymmetrical opening was carved in the earthen wall of the studio and passage allowed for body movement through the wall. The battered and staggered threshold provided logical support for the roof structural above, gracious procession for the body and exposed the time-tested earthen core.

“One lives in a secure area defined by certain geographical powers, often mountains, that relate one’s body to the environment. I fully feel this. In Tucson, where I grew up, the Catalina Mountains are North, travelling north towards a certain point in their façade is “going home.” The Rincon Mountains on the East are where Lake Michigan is in Chicago and the shore in New Haven; South is Nogales Sonora, Hull House and Ostia Antica.” Artspace

Chafee carefully arranged each room in service of life and work intertwined. Light was brought into each space from multiple directions through existing openings and subtractions in the roof plane. A north-facing skylight illuminated the area of work in the studio and a simple square opening near the dining table directed attention from the studio deep into the complex.

“One should always live in view of where one’s umbilical cord is buried. My umbilical cord flew as polluting matter with odors of the stockyards over Chicago and perhaps contributed one pinpoint of grey to the grave of Louis Sullivan. The first connection must be respected and then we who have gone far afield, albeit taking the Catalinas and the Rincons with us for reference, must accept that our umbilici feel their former adhesion to what scholars have long called the “birthplace” of this and the “cradle” of that.” Artspace

Judith Chafee Home + Studio Interior Details, Tucson, Arizona Glen Allison Photography, circa 1970.

Along with Chafee’s Architectural practice, she would continue writing poetry and prose throughout her life— a practice that she began at a young age and continued at Bennington College under the activist art historian, Alexander Dorner and poet, Harold Nemerov. In her writing, as in the architecture, Chafee found inspiration in quotidian moments and often elevated daily routine to ritual importance through the careful creation of space, the modulation of light and the mindful recognition of regional intelligence.

References

John Dewey. Art as Experience (New York, NY: Berkley Publishing Group, 1934)

Judith Chafee. “Region of the Mindful Heart.” Artspace, volume 6, number 2 (Spring 1982)

Alexander Dorner, The Way Beyond ‘Art.’ dedicated to John Dewey (New York, NY: Wittenborn, Schultz, 1947)

Edith Rose Kohlberg. “A Battleground of the Spirit.” Mademoiselle, volume 63, number 1, (May 1966) Muriel Thayer Painter. A Yaqui Easter (Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1950)

Geoffrey Scott, The Architecture of Humanism (London: Constable and Company Ltd, 1935)

Edward H. Spicer. The Yaquis: A Cultural History (Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1980)