Yiorgos Hadjichristou

University of Nicosia, Nicosia, Cyprus hadjichristou.y@unic.ac.cy www.unic.ac.cy www.yiorgoshadjichristou.com

Introduction

The paper will explore the interrelationship developed among the Dead Zone, which cruelly divides the island of Cyprus, and a new way of living in an intervention in a traditional house of Kaimakli in Nicosia. It will argue how the former gradually transformed into a porous creative entity tends to start reuniting instead of separating affects the living unit triggering new qualities into its inhabitation.

‘Dead Zone’ and ’Building a paradise’.

Juhani Pallasmaa at his lecture ‘The Aura of Sacred’ discusses ‘the experience of spirituality evoked by a work of art and architecture’. He emphasizes Aalto’s understanding on the issue: ‘Architecture …has an ulterior motive …the idea of creating paradise. That is the only purpose of our buildings. We wish to build a paradise on earth for man’.

In contradistinction to the ‘paradise’, the Dead Zone in Cyprus violently introduced an abrupt disruption of the island’s Eden, constantly reminding of the war and all the consequent predicaments.

This dividing ‘Green Line’ still dictates a geographical, political and cultural dissection of the island. The situation in the capital is eloquently rendered by Mohammad al-Asad in his introduction to the Aga Khan awards: ‘What was once a central and commercially vibrant quarter became, at a stroke, an uninhabited no man’s land. The adjacent areas to the north and south also deteriorated as the organic links between neighborhoods were abruptly severed’.

The no-man’s land is defined by Papadakis as ‘the place which joins and divides presumed oppositions such as those between Greeks and Turks, Christians and Muslims, East and West…’

The ‘Green Line’ as an ecological wonder’

However, the ‘Green Line’ completely fails to prevent the trespassing of images, sounds and whispers, smells and symbols that define the two prevailing cultures.

Optimistically and poetically it is referred in the ‘Stitching the buffer zone’ discourse: ‘It is not really a line, not very visible… it forms an interstice of land that encapsulates much pain…it is a landscape of memory …a chasm of traumas, it will flourish into a beautiful scar, a peaceful paradise, an Eden of ecological wonders where the lemons will become less bitter and Aphrodite will converse with Venus, Mary and Uhm Haram in a joyful song of Angels’.

Multicultural strips along the no man’s land

The Dead zone unobtrusively reverberates and imperceptibly transmits its ‘forbidden heavenly’ environment. No wonder that along it definite groups of people are attracted. The actual reasons may vary from clearly economic restrictions to spiritual and cultural pursuits. Though, as it usually happens in similar ‘disputed’ environments, diverse groups of locals and immigrants of different nationality and religions, as well as people with non-religion but spiritual awareness are driven along the border zone, enhancing its multicultural scene.

For the introduction to the ‘Architectural Uncanny’ Antony Vidler refers to Homi Bhabha’s: ‘speaking of the return of ‘migrants, the minorities, the diasporic’ to the city, ‘the space in which emergent identifications and new social movements of the people are played out’” and “comprehension of how ‘that boundary secures the cohesive limits of the western nation may imperceptibly turn into a contentious internal liminality that provides a place from which to speak of, and as, the minority, the exilic, the marginal and emergent’.

These multicultural conditions flank the Green Line in both sides injecting a vibrant energy, thus enhancing more the porosity to the ‘Border’. The resulting enriched permeability of the restricted Dead Zone, leads to the almost blurring effect of the parallel zones, with a tendency of fading its dividing quality and merging the zones into ‘oneness’.

These contrasting and juxtaposing characteristics of the Dividing Line transform it to a major catalyst for any intervention, including naturally the primary human need for finding a place for a shelter.

Hora: A place or non-place?

Pallasmaa points out that ‘the origin of architecture is about to provide a physical shelter … however the primary task of architecture is to create the experience of placeness…’

Accordingly to Heidegger’s ‘Building Dwelling Thinking’: ‘a distinction between space and place, where spaces gain authority not from ‘space’ appreciated mathematically but ‘place’ appreciated through human experience’.

Papadakis embarking on a tour of Hora- the intimate name of Nicosia, puts the question:’Hora is –or is not-constituted as a ‘place’ in the light of de Certeau’s and Auge’s understanding of places’. He concludes the former’s definition of ‘place: the reinterpretation of proper place by acting local agents as they fill the landscape with personal, familiar, or generally local meanings and stories’ and the latter’s: ‘places: are linked with history, ancestors, the recently dead and ritual timetable’. Randall Teal argues that in order to discover the richness of ‘‘place’’ through architecture, the designer must engage with the specificities of culture, location, and experience that make up everyday existence.

Is the identity of this ‘place’ or ‘not place’ defined by the so called Dead Zone or by its alter-ego, the ‘Green Ecological wonder, or finally by the emergent of the new multicultural milieu? Can the unique case of the last divided capital produce a new way of living?

Emergence of the new Living

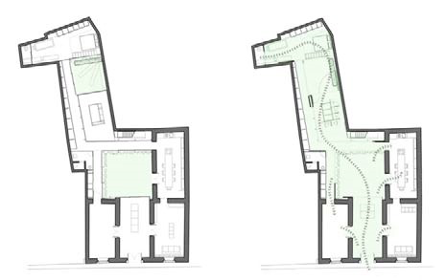

In the Kaimakli case, an essential extension of a ‘truncated’ traditional house attempted to capture the challenging qualities of the (non-) placeness of the Unifying ‘Dividing Zone’. The notion of the ‘porous’ Green ‘ dividing’ line was filtered and injected as a generating idea within the intervention , translated into a maximum flexibility within the house.

The project is sort of reflecting the notion of the Green Line, as it is an attempt to deal with a traditional house literally cut in the middle due the result of dowry arrangements concerning the family property. It is seen too as a way to heal the amputation, in its case, of its traditional spatial organization including the local legacy of the courtyard typology.

Randall Teal in relation to Heidegger’s notions, refers to the ‘immaterial structures of human existence that link our ‘‘everyday’’ activities to those moments that are extraordinary. Architectural design activates these relationships when a designer welcomes the uncertainty, contingency, and vulnerability that is fundamental to one’s being’.

These mentioned qualities are thought to be achieved through an ultimate malleability of spaces leading to a conduit between the ordinary and the extraordinary.

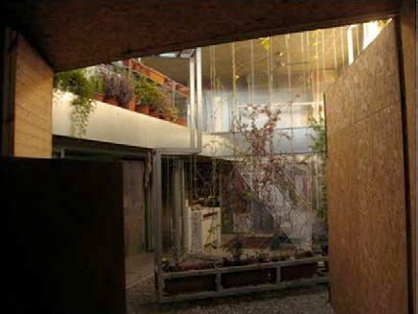

With Tom Blender’s words, ‘this house started with a love of camping, of being open to life’. This “living architecture” dissolves the demarcation between architecture and landscaping, between building and “nature”.

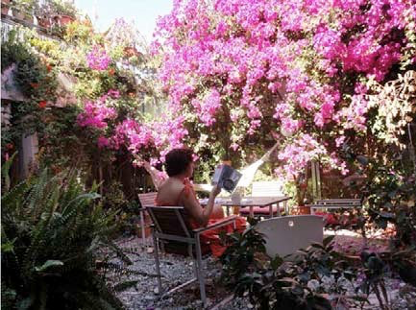

The literal final stage of the house becomes a total unification with nature as a camping site. Thus it manages to engage the nature as a constituent element in the house. Relating to Jonathan Hill’s ‘Weather Architecture’ discourse, ‘weather and nature become co-authors with architects’. This kind of intervention yields to unprecedented experiences of an ‘enlightened domicile’.

Adam Sharr discusses Heidegger’s understanding of dwelling that it ‘involved somehow being at one with the world: peaceful, contented, and liberating’. And then he adds: ‘oneness shows that black and white are indistinguishable from each other…they are part of the same totality from which individual parts can’t be extricated and known in isolation’.

It therefore attains the qualities of the ‘oneness’ as stated by Julio Bermudez referring to Ken Wilber: ‘’my experience of a building (it) must shift from ‘me’ and ’it’ as a duality, to just an experiential oneness where subject and object are merged.”

The house is perceived as the juxtaposition of the simultaneously present and mingling dualities that interweave the resulting spatial conditions, creating an abundance of experiential environments for its users. It is experienced as a constant transformation of the internal and, consequently, the external spaces, mingling or merging of the public and private areas, alteration of the movements and pauses, interchange of the openness with closeness, as fragmented spaces that at any moment can be converted into a united ‘place’.

The ultimate malleability and flexibility of the house allows the user to constantly alter the spatial conditions, merging himself into a unison not only with the built part of the dwelling, but with the equally constituent element of nature and weather.

Conclusion

The Dead Zone is not only seen but it is steadily becoming replete of Life as the Nature finally takes over and permeates the enforced boundaries and as the multicultural milieu is finally thriving in this vague terrain enhancing and ‘accomplishing’ the porosity of the ‘Border’. Despite the political conflict and division, the Dead Dividing strip and its flanked divided parts tend to start their reunification. The identity of this paradox inevitably affects the perception of the dwelling. Consequently, the house breaks its own boundaries, and it unites its users with the nature and the environment merging them into an ‘experiential oneness’. As the so ironically called The Green Line is converted into a reverberating Eden, the conversion of a traditional house in Kaimakli’s ‘Border Area’ is transformed into an Earthy Paradise, the only purpose of the building…

References

Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Intervention Architecture, Building for Change ( I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd 2007) Bender, Tom. The economics of true sustainability (Fire River Press 2013)

Bermudez, Julio. The Extraordinary in Architecture: Studying and Acknowledging the Reality of the Spiritual

( 2A Architecture and Art. Architecture Culture and Spirituality 2009)

Demi, Danilo. The walled city of Nicosia, Typology study (United Nations Development Programme 1997)

Hadjichristou, Yiorgos. Malleable Courtyards (AEC International Conference 2012)

Ilican, Murat Erdal. The Occupy Buffer Zone Movement: Radicalism and Sovereignty in Cyprus (The Cyprus Review, Volume 25:1 Spring 2013)

Heidegger, Martin. Building Dwelling Thinking (Harper and Row 1971)

Hill, Jonathan. Weather Architecture (Routledge, London 2013)

Holl, Pallasmaa, Pere- Gomez. Questions of Perception- Phenomenology of Architecture (William Stout Publishers, San Francisco, AU, 2006)

Solder, Grichting; Costi de Castrillo and Keszi-Frangoudi, Stitching the Buffer Zone- Landscapes, sounds and Trans Experiences along the Cyprus Green Line (Bookworm publication 2012)

Pallasmaa, Juhani. The Aura of Sacred (Catholic University’s School of Architecture and Planning in Washington, DC, 2011)

Papadakis, Yiannis. Echoes from the Dead Zone: Across the Cyprus Divide (I.B.Tauris 2005)

Papadakis, Yiannis. Walking in the Hora:’Place’ and ‘Non-place’ in Divided Nicosia (Journal of

Mediterranean Studies. History, culture and society in the Mediterranean world 1998)

Peristiianis, Mavris. The “Green Line” of Cyprus : a Contested Boundary in Flux ( The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies 2011)

Petropoulou and Hadjisavva (eds.). Nicosia: The unknown Heritage along the Buffer Zone (Nicosia Municipality, Nicosia Master plan, 2008)

Sharr, Adam. Heidegger for Architects, thinkers for architects (Routledge, 2009)

Teal, Randall. Building-in-place (Phaenex 3 2008)

Trimikliniotis, Demetriou ,Symfiliosi. Tolerance and Cultural Diversity, Discourses in Cyprus (European University Institute ,Accept Pluralism 7th Framework Programme Project 2011)

Vidler, Anthony. The Architectural Uncanny, essays in the modern unhomely (The MIT Press, 1992)

Figure 1 permeability into the Dead Zone

Figure 2 In Parts and In Oneness

Figure 3 living in maximum flexibility

Figure 4 malleability of spaces

Figure 5 experiential oneness where subject and object are merged