Karla Cavarra Britton

Yale School of Architecture, New Haven, Connecticut karla.britton@yale.edu

At the beginning of his 1921 fragment, “Capitalism as Religion,” Walter Benjamin writes, “One can behold in capitalism a religion, that is to say, capitalism essentially serves to satisfy the same worries, anguish, and disquiet formerly answered by so-called religion.”1 Among the characteristics of this capitalist religion, Benjamin notes that it “is a pure religious cult. … Within it everything has meaning only in relation to the cult.” It is a powerful statement that asks the reader to consider the parity of two seemingly incommensurable cultural systems (the religious and the economic), but the two become inseparably intertwined through the act of consumption. Benjamin’s text suggests that capitalism correlates with religion not only in its cultic potential, but also at its most immediate practical level in the projection of an “ideal” and “transcendent” character.

Today there is abundant evidence for the aptness of Benjamin’s assertion: places of natural beauty and cultural significance that once served as sites for retreat and contemplation are now integrated into a worldwide system of consumptive criteria and protocols. The experience of nature and other ordinary things imbued with special meaning for individuals, societies, and cultures—the very subject of this conference—is now more often than not diffused into and articulated through a worldwide market. Both the dangers and advantages of this spatial interconnectedness for human experiences of spirituality and the search for meaning are great.

In his essay on “The Secular Spirituality of Tadao Ando,” Kenneth Frampton begins by stating, “The tautology of a secular spirituality surely touches on the crisis that lies at the heart of a good deal of contemporary culture.” This crisis is none other than the reduction of the ultimacy of human experience to various forms of consumption, as Benjamin’s notional idea of capitalistic religion suggests. While Frampton posits that Ando’s work “postulates the continued existence of the sacred and profane,” he nevertheless observes in what is familiar to us by now as the idea that institutions such as the art museum—a mode of consuming aesthetic experience par excellence—now stand in as the “surrogate religious institutions of our age.”2

Although Kenneth Frampton does not clarify with any great specificity his definition of secular spirituality, it is clear from his text that it concerns a cosmogonic spirituality that, as Jos Boys observes, relates “two chains of associative concepts which are conventionally oppositional: “external / universal / functional / secular and internal / unique / spiritual / religious.3 It thus transcends the split between the sacred and profane, and the body and soul, that are central to the ethos of monotheism. In its place is projected through architectural form instead a primal, non-animistic and ambiguous spiritual presence driven by a pantheistic understanding of the “revealed ineffability of nature” and of light itself as a mediating medium.4

There is not one architect or specimen of architecture, of course, that can exclusively sum up an understanding of the idea of secular spirituality or express its consequences. Yet what I want to explore in this paper are two salient examples of contemporary architecture that express this kind of association of something overtly profane and secular in their intentionality and thus share in many of the tropes of both Benjamin and Frampton’s identification of a secular form of spiritual existence. In the first instance, there is the project under construction at Grace Farms in New Canaan, Connecticut, designed by the Tokyo-based firm SANAA and known as “The River” in an undeveloped tract of land in one of the wealthiest communities in the nation; and in the second instance, there is an unrealized project proposed by the Swiss firm Herzog & De Meuron known as “El Punto” in the Ciudad Juarez—the border city across the Rio Grande from El Paso made infamous for its gang violence, government corruption, and poverty.

In terms of “new” and experimental paradigms for religious buildings, it would be difficult to find more conceptually revelatory examples. For while both projects have an overt portion of their building space given over to worship space, both eschew in name and in description any deliberate programmatic emphasis on liturgical functions. Instead these projects are complexes with multiple goals including communal gathering, artistic exploration, and social justice and service. Indeed their very titles—The River and The Point—signal a geographical landmark open to interpretation. In this regard the self-descriptive “Architectural Directive” of Grace Farms is telling: “To create a venue of cultural interest and curiosity via open space, architecture, art and design in hopes of providing people with a chance to do the following: 1. Experience Nature … 2. Participate in a Meaningful Community … 3. Serve Others … 4. Explore Faith …”5

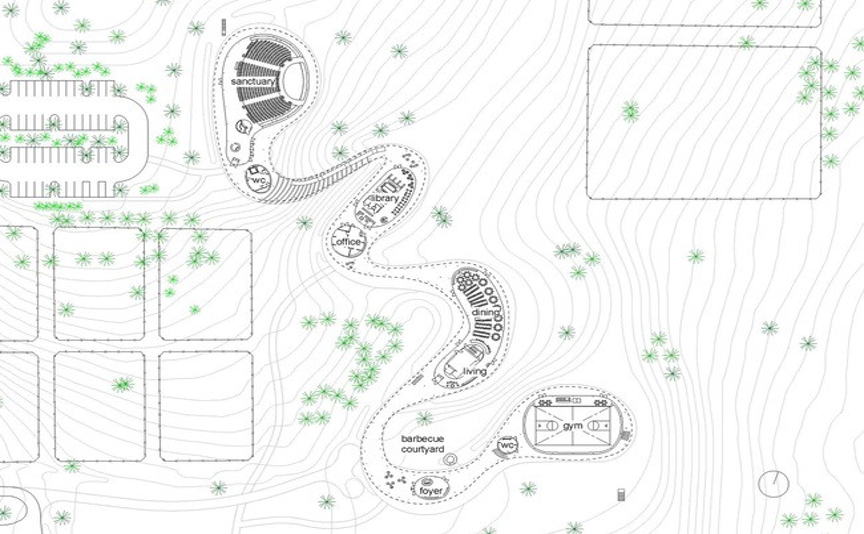

Nature plays the determinative role in “The River.” Located on an extensive 75-acre former horse farm that is intended as both a nature preserve and church location (scheduled to open this October), The River is essentially a long, low roof that disappears into the landscape as it meanders in a serpentine pattern through the sloping site, creating both courtyards and buffered spaces, or “pods,” that are sheathed in glass. The transparent pods enclose a gymnasium, library, kitchen and dining room, and cinema in addition to the worship space—make striking use of custom designed glass panels that are often a hallmark of SANAA’s design for museums. The importance of “openness” is made abundantly clear in the interview given by SANAA’s two partners, Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawz, about their 2002 design for the New Museum in New York: “We design museums that concern themselves with the future by thinking about openness, which manifests itself as room for new possibilities . . .”6 Programmatically this means that The River is intended for any number of possible functions—and so it lends itself to the spiritual projections of its visitors rather than suggesting any fixed denominational point of reference.

The worship space transfers one’s attention away from the interiority of the building and the program of liturgy, toward the impinging spiritual presence of the natural world outside (whether it be a summertime field of green and wild flowers, or a winter scene of snow and ice). Here the ambiguous religious associations of the building’s program are informed by the ambivalent assertion that nature itself will be the driving spiritual force behind this “church.” One might say that The River takes many of the instincts of the box church and puts them in relation to landscape and nature. While it therefore suggests on some programmatic levels the mega-church phenomenon, it also moves far beyond it architecturally by introducing a spiritual interaction with the natural environment.

In contrast to the natural serenity of The River, Herzog & de Mueron’s El Punto is an urban intervention designed to foster economic growth by drawing tourists to an otherwise blighted environment. It is simultaneously a cultural and educational center, immigration facility, outdoor theater, and chapel. The project is thereby communal, urban, and economic in shape. The clients for the project have been willing to take considerable risks: its experimental nature suggests a new and more open paradigm for spiritual architecture—one that evokes a secular commitment in which a community’s well-being is tied to its economic as well as spiritual health.

These two articulations of the sacred—The River and The Point—may be understood as selfconsciously leaving tantalizingly open the question of how the religious community for which the buildings are intended will choose to inhabit the space. Perhaps what one sees in both projects is that the idea of a temple where human activity is directed toward the gods, has been supplanted with an architectural conception of sacred space where it functions as a resource for sacralizing human activity. Like the archetypal aestheticism of the contemporary art museum, the sacred becomes a mode of experience that one appropriates to one’s own need—a consummation of Benjamin’s observation that capitalism—whose essence is consumption—can “satisfy the same worries, anguish, and disquiet formerly answered by so-called religion.”

Grace Farms, aerial view, showing The River at top. Copyright Grace Farms and SANAA.

The River, perspective. Copyright Grace Farms and SANAA.

The River, site plan. Copyright Grace Farms and SANAA.

El Punto, model. Copyright Herzog & de Meuron and Arquine.

El Punto, rendering of interior of worship space. Copyright Herzog & de Meuron and Arquine.

- Walter Benjamin, “Capitalism as Religion” a translation by Chad Kautzer of Fragment 74, entitled “Kapitalismus als Religion” from Volume VI of Benjamin’s Gesammelte Schriften, Rolf Tiedemann andHermann Schweppenhauser, eds. (Suhrkamp, 1991), 100-03; http://www.rae.com.pt/Caderno_wb_2010/Benjamin%20Capitalism-as-Religion.pdf, accessed 5/21/15

- Kenneth Frampton, “The Secular Spirituality of Tadao Ando,” in Constructing the Ineffable: Contemporary Sacred Architecture, ed. Karla Britton (Yale, 2010), 96-112.

- Jos Boys, “(Mis)representations of Society?” in Design and Aesthestics: A Reader, ed. Mo Dodson and Jerry Palmer (Routledge, 2003), 237.

- Frampton, 99.

- Grace Farms, publicity brochure published by the Grace Farms Foundation, n.d.

- “The artwork is never an added difficulty,” Conversation with Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, in SANAA: Sejima & Nishizawa New Museum New York (Ediciones Poligrafa, Barcelona, 2010), 15-29.